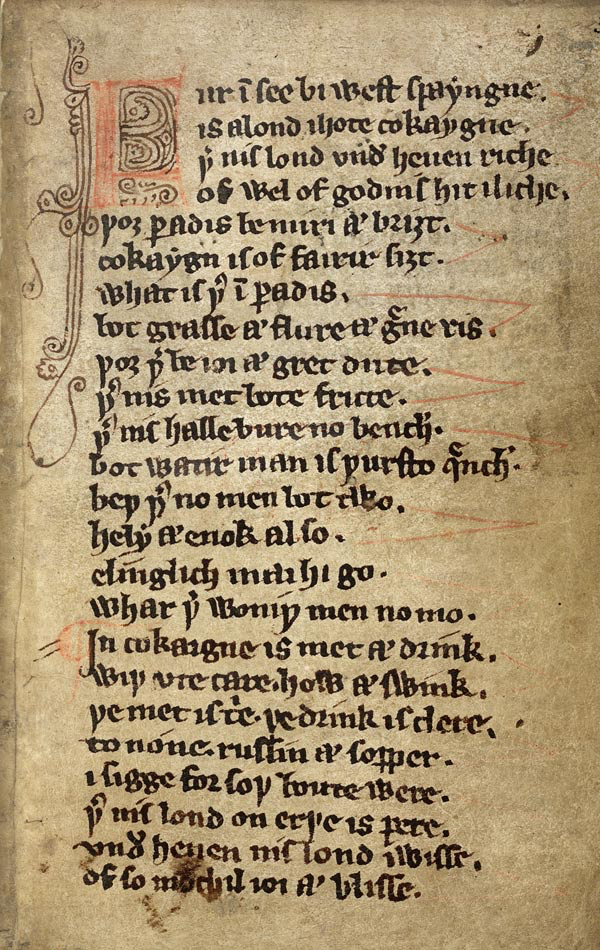

Front Plate 1. Land of Cockaygne – from London, British Library, MS Harley 913 (formerly “The Kildare Manuscript”)

What you will find in Opening Up

“Land of Cockaygne” (hereafter LC) is Opening Up’s first Front Plate, chosen to represent a bookhand (Gothic textura semiquadrata) from a famous manuscript, and also one of the best-known satires in the Early Middle English canon. It was composed not in England but Ireland, exemplifying the relatively early rise of Anglo-Irish poetry with a sophistication far outstripping (for instance) London’s in this period. Front Plate 1 offers an image of the poem from Harley 913 showing the first leaf with facing transcription, analysis of its script, and discussion of its cultural hybridity on various levels, including its linguistic borrowings from Irish Gaelic, paleographical borrowings from Latin, and its transcultural literary character. It was copied with rhyme brackets to aid performance or reading, and it has much in common with other poems in the Harley 913 collection (traditionally called “The Kildare manuscript,” though likely originating in Waterford). Opening Up situates both LC and the illustrated MS Douce 104 Piers Plowman (Front Plate 8) in their colonial context as a product of “the middle nation,” as Anglo-Irish settlers saw themselves, sandwiched between their Irish-speaking neighbours and the English. See OP, Front Plate 1; and Front Plate 8, also Anglo-Irish.

What is new in Harley 913 Studies? “The Land of Cockaygne” Scholarship since 2012

Deborah Moore’s Medieval Anglo-Irish Troubles: A Cultural Study of B.L. MS Harley 913 (Turnhout, 2017), as she explains in her Preface, is the first book-length literary study to take “a more holistic” approach to the Harley 913 lyrics by going “back to the manuscript itself for primary source information” (10). Moore’s study is unique in that it devotes equal attention to texts in all three of its languages (Latin, Hiberno-Norman French, and Middle Hiberno-English), covers codicological and literary aspects of the manuscript, and follows the exact order of the texts in this complex miscellany. Happily, any reader can now also read the poems in this order themselves by accessing the original manuscript newly digitized online and using Moore’s volume as an interpretive guide. See the British Library’s digitized version: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_913

On “Land of Cockaygne” itself, Moore offers several key insights, including how it relates to the twelfth-century Irish wonder tale, Aislinge Meic Conglinne (‘The Vision of MacConglinne’),[1] with its folk tale motifs and list of tempting Irish foodstuffs much like LC’s parallel culinary treats (which however are decidedly English!). LC also shows, Moore argues, “goliardic reformist sentiments, yet differs in its distinct origins in the Anglo-Irish community” (64). The LC poet parodies “the Irish visionary ‘Otherworld’ descriptive motifs” (65), while following “the true spirit of goliardic tradition,” in which “the clearly well-educated poet invests the speaker with a naïve and awe-struck persona,” a motif seen repeatedly in the satiric Harley works. However, as she rightly notes, “the cultural allegiance [of this persona] is initially wholly ambiguous” (65). But the prominence the poet gives to Elijah and Enoch, whose legends had special and even apocalyptic influence in Ireland, is distinctly Irish. Traditionally, Elijah and Enoch were believed to have been “bodily” transported to the Earthly Paradise (which the poet exploits to create Cockaygne) to await the end of the world. The famously salacious and erotic nature of the LC’s monks’ wild exploits with local nuns in this “paradise” can also be paralleled, as Moore notes, in Celtic visionary ‘Otherworld’ texts (e.g., with motifs such as “monks that turn into birds” or “the absence of sin in sexual encounters” (68)). The LC poet pointedly suggests that the monastic order represented in this mythical “wel fair abbei / Of white monkes and of grei” (lines 51-2) are the Cistercians: “the added irony here is that the Cistercian Order originally had the task of reforming the long-isolated Gaelic-Irish monasteries,” before they, too, “became more corrupt” (67). Moore also explores how the compiler of Harley 913 (likely a friar) wields anti-monastic polemic throughout the manuscript, since “nine of its fifty-eight works concern the sinful behaviour of monks” (69-70), a reminder that inter-clerical polemic lies at the root of 913’s most famous satire.[2]

Another extremely helpful publication since 2012 is Thorlac Turville-Petre’s finely edited EETS volume of the Middle Hiberno-English Harley 913 lyrics. It also takes a holistic approach to the manuscript and its Anglo-Irish cultural setting. As reviewer Anne Marie D’Arcy noted, this edition is “distinguished by the linguistic precision, care for codicological probabilities, and sensitivity to historical shading we have come to expect from the editor. In addition to a searching analysis of the social and political events, and the cultural milieu which inform this dismembered and rearranged manuscript of the 1330s,…it firmly situates 13 of the 20 edited texts known as the Kildare Poems (based on the ascription of one of the Middle English poems to ‘Frere Michel Kyldare’ at fol. 10r) in a Hiberno-Norman setting on phonological and morphological grounds.”[3] Turville-Petre refers to “Land of Cockaygne,” the manuscript’s first (in its current state) and most famous lyric, succinctly as “a fantasy of a culinary and sexual earthly paradise,” situating it among the manuscript’s 17 English poems, 3 Anglo-Norman poems, and many Latin items. Turville-Petre even covers British Library, MS Lansdowne 418, a seventeenth-century copy of 11 of the Harley 913 texts, including 5 now wholly lost.[4]

A somewhat different approach to LC, equally crucial, is the pan-European view of the late Peter Dronke’s exploration of classical, continental, and manuscript sources for comparison. As a renowned specialist in medieval Latin literature, Dronke was able to compare LC to other Latin poems, and with some startling results: “My impression is that, compared with the finest Latin satiric poets of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the English poet does not show any of the[ir] moral fervour…nor are his observations bitter or malicious…. Among the major medieval Latin poets, he seems to me closest in outlook to the Archpoet – a generous spirit for whom criticism and sheer enjoyment were often inseparable” (74). This is striking praise from a Medieval Latinist for a Middle-Hiberno English poet. Another of Dronke’s insightful observations is that the poet’s own viewpoint is “that of the poorer, lower orders of clergy” (75), which would make him a member of the clerical proletariat.[5] In his subsection, “Latin Evidence in the Harley Manuscript,” he draws in the Latin works of Harley 913 to better understand LC. He remarks that three Latin works (“The Drinker’s Mass,” “The Office of the Seven Sleepers,” and the “Prose Letter to the Prince of Hell”) have in common with LC a parody of corrupt (usually regular) clergy, all exuding an attitude of “reluctant, perhaps envious admiration (how do they get away with it?)” (72). Dronke’s “whole manuscript” approach is not codicological, nor does it emphasize Ireland, but it is holistic because he does read the poem in relation to Harley’s other contents; moreover, his pan-European treatment of LC’s Goliardic roots allows him to make some striking discoveries.[6] Among these is perhaps even an overlooked source for LC, a parodic Latin letter originally from Italy, inc. “Lucia, venerable abbess of Cokaygne [Cucanacanse],” written by a rhetorician and notary, Henricus de Isernia. One of the Prester John texts, it calls upon Lucia’s nuns to cast aside modesty and reject the rule of chastity to pay tribute to Venus as the day of salvation approaches (70-71). Dronke examines this alongside other satirical “Cucania” texts lampooning the abbots or abbesses, providing a remarkable window on the LC poet’s and the Harley manuscript compiler’s intimate knowledge of Latin across European borders.[7]

A major codicological and political recontextualization of Harley 913 appeared in John J. Thompson’s “Books Beyond England,” whichmakes the point that though we still do not fully understand the motivation for Harley 913’s often irreverent collection, this “battered relic of a trilingual literary culture…reflects an interest in Franciscan practices and Irish marcher culture” (the latter too often ignored).[8] Thompson also astutely critiques modern binary assumptions about Ireland: “Ironically, of course, to view Irish and English cultures in fourteenth-century Ireland as unproblematically separate and confrontational—as nearly all previous commentators on the Harley 913 manuscript have done at one time or other—is ultimately the work of an imperial agenda and ideology.”[9] He reminds us that these cultures were more interwoven than the casual colonial (“imperialist”) reading suggests, which reminds us of Moore’s astute observation of the speaker’s ambiguous stance. Thompson, too, advocates that critics stay alert to the voices of those who navigated cultural borders (a point also discussed in Opening Up’s Front Plate 8). Thompson exemplifies the kind of 21st-c. scholarship attempting move beyond binaries and focus on the culture of those in Ireland “who lived and moved across…boundaries.”[10] Thompson’s views remind us of what historians have long taught about the distinctiveness and comparatively multicultural character of Ireland’s late medieval period. As Katharine Simms wrote (“The Norman Invasion and the Gaelic Recovery”): “One fascinating aspect of Ireland’s history during the later Middle Ages is the gradual blurring” of the “deeply felt divisions” that Gerald of Wales had articulated two centuries before, “until fresh lines were drawn on the basis of religious affiliation” in the sixteenth century.[11]

The society that produced LC, then, was a complex one: allegiances during both peace and war could be mixed, for reasons ranging from local pragmatism to assimilation. Other sources attest to the deep attractiveness of Irish literary culture, which as we saw, the poet feels free to draw upon with exuberance.[12] For a manuscript nearly universally discussed as Franciscan, Thompson, as we saw, emphasizes that the Harley 913 compiler was also interested in Irish marcher cultures, particularly of the Kildare and Waterford areas.[13] Most extant early Middle-Hiberno English literature, he notes, comes from “the obedient shires” of eastern Ireland, most often from stronghold marcher towns such as Waterford, New Ross, and Kildare, all of which (as discussed below) are implicated in the making of Harley 913.[14]

This marcher culture has been far less studied by literary historians. Among key recent attempts to redress this particular imbalance is Keith Busby’s landmark study of Hiberno-Norman French texts in Ireland, including those in Harley 913. Waterford, where Harley 913 was likely compiled, was, as Busby carefully established, the centre of French culture in Ireland. In fact, we are only beginning to reconstruct this diaspora city’s cultural history, a city that also fostered a Hiberno-Norman friar, Jofroi de Waterford, who translated the popular Secreta secretorum into French, giving it its first great currency in Western Europe.[15]

The complexity of these trilingual diaspora town settings from which Harley 913 and many of its contents came is the subject of two recent studies by Kathryn Kerby-Fulton. In “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture of Ireland” (2021), I note that “Despite its famous and iron-clad Franciscan credentials, even Harley 913 contains lyrics with detailed civic and bureaucratic content,” reflecting marcher towns like Waterford as settings for experimental or nascent Hiberno-English written culture. This article, following upon a 2020 one (“Making the Early Middle Hiberno-English Lyric: Mysteries, Experiments and Survivals before 1330”), addresses “long-standing mysteries [as to] why and how the highly sophisticated early Middle-Hiberno English lyrics in Harley 913 emerge by c. 1330 from a virtually unknown literary context.”[16] This article opens a window on the civic precedents to the lyrics of Harley 913, noting that by the end of the fourteenth century (if not sooner), this Franciscan manuscript garnered “a Latin ownership inscription (fol. 29r) to John Lombard of Waterford, who was Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1395, and Mayor of Waterford 1406–8.” Given the civic and bureaucratic content of many of the poems, such urban interest in Harley 913 should not surprise us. “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture” also compares some of the more dramatic elements in LC with Harley 913’s “Satire on Sinful Townsfolk,” a poem reminiscent of “‘Land of Cockaygne’ [and its] daring critique of Paradise’s prophets,” since it, too, makes shocking fun of many saints.[17] These kinds of connections have been obscured by modern anthologization of LC, which is often printed alone among Early Middle English texts, ever since Bennett and Smithers’s influential edition.[18] In “Making the Early Middle Hiberno-English Lyric,” I also update some of the evidence of linguistic borrowings from Irish Gaelic in LC and examine poetry earlier even than Harley 913’s, rarely studied elsewhere.

All in all, it is remarkable that a collection the size of Harley 913 survives at all, “the English poems of which constitute the earliest substantial body of English verse in medieval Ireland,” as Marjorie Harrington succinctly puts it.[19]

Bibliography

London, British Library, MS Harley 913, digital version:

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_913

K. Busby, French in Medieval Ireland, Ireland in Medieval French: The Paradox of Two Worlds(Turnhout: Brepols, 2017).

Peter Dronke, “The Land of Cockaygne: Three Notes on the Latin Background,” Medieval Latin and Middle English Literature: Essays in Honour of Jill Mann, ed. C. Cannon and M. Nolan (Cambridge: Brewer, 2011), 65–75.

Anne Marie D’Arcy, Review of Poems from MS Harley 913: ‘The Kildare Manuscript’, ed. T. Turville-Petre, EETS OS 345 (Oxford, 2015), xxxvii–xli, in The Review of English Studies, Volume 67, Issue 282, November 2016, 991–992, https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgw043.

K. Kerby-Fulton, “Making the Early Middle Hiberno-English Lyric: Mysteries, Experiments and Survivals before 1330,” Early Middle English 2.2 (2020), 1–26.

Kerby-Fulton, “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry and the Nascent Bureaucratic Literary Culture of Ireland” in Scribal Cultures in Late Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Linne R. Mooney, ed. Margaret Connolly, Holly James-Maddocks, and Derek Pearsall (Woodbridge, U.K.: Boydell and Brewer, 2021) 45-64.

D. L. Moore, Medieval Anglo-Irish Troubles: A Cultural Study of BL MS Harley 913 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017).

Poems from MS Harley 913: ‘The Kildare Manuscript’, ed. T. Turville-Petre, EETS OS 345 (Oxford: Clarendon, 2015), xxxvii–xli.

John J. Thompson, “Mapping Points West of West Midlands Manuscripts and Texts: Irishness(es) and Middle English Literary Culture,” in Essays in Manuscripts Geography: Vernacular Manuscripts of the English West Midlands, ed. Wendy Scase (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 113–28.

John J. Thompson, “Books Beyond England,” in The Production of Books in England, 1350–1500, ed. A. Gillespie and D. Wakelin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 259–75.

I would like to thank Theresa O’Byrne and Hannah Zdansky for their specialist advice on Irish culture and their close reading of this essay.

[1] Ed. and tr. Lahney Preston-Matto (Syracuse U. Press, 2010).

[2] See also Front Plate 8 below, and on the differences between inter-clerical and anticlerical polemic, see “‘Anticlericalism,’ Inter-clerical Polemic and Theological Vernaculars,” co-written with Melissa Mayus and Katie Ann-Marie Bugyis, Chapter 27 of The Oxford Handbook of Chaucer, ed. Suzanne Conklin Akbari and James Simpson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 494–526.

[3] Anne Marie D’Arcy, review of Turville Petre, 991-2: https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgw043.

D’Arcy continues: “This concurs with previous editions by Wilhelm Heuser (1904) and Angela Lucas (1995) and stands in marked contrast to more recent studies by Neil Cartlidge (2003) and Peter Dronke (2011).” But Dronke provides classical, Irish, and codicological contexts too (see below).

[4] See Turville-Petre’s description: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/poems-from-bl-ms-harley-913-9780198739166?cc=us&lang=en&#.

[5] For this class, see Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, The Clerical Proletariat and the Resurgence of Medieval English Poetry (Philadelphia: U. Penn. Press, 2021).

[6] See Dronke’s “The Land of Cockaygne: Three Notes on the Latin Background,” subsection II, “Cucania.”

[7] For a Dublin parallel to this pan-European literary perspective, see “Centre or Periphery?: The Role of Dublin in James Yonge’s Memoriale,” Dublin: Renaissance City of Literature, ed. Kathleen Miller and Crawford Gribben (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017) 16-37.

[8] Thompson, “Books Beyond England,” 261–2. See, too, Kerby-Fulton (2021) discussed below.

[9] Thompson, “Mapping Points West,” 122.

[10] Thompson, “Mapping Points West,” 117 and 127 (my emphasis).

[11] Simms, in The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland, ed. R.F. Foster (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 54.

[12] See discussion of Front Plate 8 below.

[13] John Thompson, “Books Beyond England,” 261. See Kerby-Fulton, “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry,” for a full recent discussion of “Satire on Sinful Townsfolk” and “Retrenchment.”

[14] Thompson, “Books Beyond England,” 261 and map, Fig. 12.1.

[15] Busby, French in Medieval Ireland, 150. As Busby shows, Jofroi’s co-translator, Servais Copale, was a wealthy Waterford civic administrator and merchant, an immigrant from Liège.

[16] “Middle Hiberno-English Poetry,” forthcoming 2021.

[17] Kerby-Fulton, “Making the Early Middle Hiberno-English Lyric.”

[18] J. A. W. Bennett and G. V. Smithers, Early Middle English Verse and Prose (London: Oxford University Press, 1968), 138–44.

[19] Marjorie Harrington, “Of Earth You Were Made: Constructing the Bilingual Poem ‘Erþe’ in British Library, Harley 913,” Florilegium 31 (2014): 105–38, at 114.