By Grace Andrews

Week three has broken us into a new way of working, a fresh dynamic from which we are making bold new discoveries and mining deeper into this heady and huge expanse of text. The initial feeling of distance, the fear of not being able to reach the height of the words, or breadth of the ideas, begins to fade – and slowly we start to feel like we are closer to something real. With that growing sense of ownership, our appetite for the play now holds a confidence with a sense of focus – proven in the way we interact. We are more direct, more economic, and more passionate but perhaps less precious. We listen more. We systematically try things out, and equally throw things away.

One of the main challenges of this job is being able to operate on multiple levels. You play the part, you play the scene, you keep an outside eye on the space, you keep a sense of the arc of the story as a whole, and you think of set, you think of costume, multiple parts, appreciating and catering for the company and American audiences… the list goes on. There is a constant sense of zooming in and out, honing in and stepping back to keep the wheels turning over. Within this – the test is to remain in the moment, and never lose sight of the meaning and heart of the storytelling. As we work further into detail, our thoughts on design are contested with the question – what is important here? What do we want our audiences to experience? How much can we relinquish that control? The danger to prioritise style over substance can be tempting, but the harder choice is to ask ourselves, are we really telling this story?

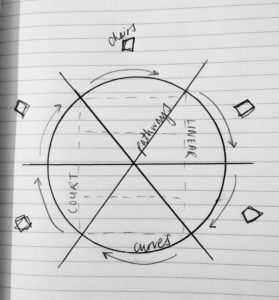

That said, we have had some major breakthroughs in terms of the space we create. Hecate is an Athenian goddess who represented as three-formed, associated with crossroads, entrance-ways, light, magic, and necromancy – used in Hamlet precisely in Act III, Scene II in the play within the play, ‘The Murder of Gonzago’. Her spirit is woven all throughout the writing, and subliminally creates strong impact with many references to ‘three’, and cyclical and swirling swings even within the verse line. She is known for her wheel, and we have marked out a wheel on the floor (left), which offers us a structure from which to play.

We work with a Complicité exercise, where we follow each other on a journey through the space and pause at the junctions marked, with suspension, and then move on together. The wheel gives us the freedom of curves, but a discipline of distance, and a chance to explore our relationships, and find specificity in the meaning of eye contact, breath, silhouettes and energies. We are forced to face up to the change each character creates in space. We draw our characters out on paper to explore and make tangible decisions (left).

Peter Bray offered a brilliant take on the world of the play this week that ignited a breakthrough in me. He said that the play was all about the death of intimacy in our closest relationships. In varying levels of intensity, each bond of any purity or worth is systematically, grievously, irrevocably and deeply destroyed – whether it be fierce young love, a mother to a son, a son to an uncle, a brother to a sister, a daughter to a father, a friend to a friend. The list is long, and the loss unites this story with a raw and feverish ache. I think about our wheel, and the spaces between us. The endless potential for love and loss between two humans in space. Shakespeare transcends time, cuts right to the heart, and cries out to be heard.