Last week, I finally got over my fear of using the phone and called in a lunch order for me and a friend at Girasol, a pupuseria in South Bend. I usually avoid using the phone, I would much rather text someone or talk in person, but Luz Ferrufino, the Salvadoran woman who owns the restaurant, prefers her customers to call ahead so that she can have their food ready as they walk in the door.

Luz answered the phone quickly, startling me as I was running through my prepared order.

“Hello?” she said, with a slight accent. It wasn’t obstructive to the conversation, but it was enough to signal the she had not grown up speaking English.

“Um… may i order some pupusas to pick up in half an hour?” I replied.

“Yes, one half hour” she repeated back to me.

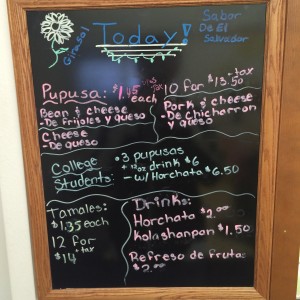

“Excellent, what kinds of pupusa do you have?” A pupusa is a small corn flour wrap, stuffed with either beans, meat, cheese, or a combination of the three. Served warm, one could eat three or four in one sitting happily. In fact, Luz offers a special for college students, her most common customers: a small discount if you order three pupusas and a horchata. She also offers catering, and can make large amounts of pupusas at once in her kitchen.

“Pork, Cheese, and Beans” she said matter-of-factly. Excellent! These are the three main varieties, and it was no surprise that Luz offers all three, since pupusas, a traditional Salvadoran food, are the main dish she serves. She also serves Salvadoran tamales, which are slightly less spicy than the more popular Mexican tamales.

The pupusa has a long history. They date back to Pre-Columbian times, when the Pipil tribes, who live in the area now known as El Salvador, cooked them using primitive tools over 2000 years ago. In fact, “pupusa” is a word in the indigenous Pipil language, the name given to the particular dish.(1) There are variants, depending on where in Central America you are, and one of the more closely related versions is called the gordito. As you might guess, it is larger, and has more filling. I could easily eat at least four pupusas in one sitting; I’m not so sure about the gorditas.

Feeling adventurous, I ordered two of each type of pupusa, as well as a horchata. As she read my order back to me, I nodded, then, remembering I was on the phone, verbally agreed. After I hung up, I realized that Luz had never once said the name of the restaurant during our conversation; she was casual, as if I had talked with her hundreds of times before. I was slightly disappointed vaguely by this realization, however, because although I had discussed Girasol with a number of friends (as an anthropology major, you end up eating at a lot of ethnic restaurants), I had never gotten a definitive answer on how exactly to pronounce the name of the place.

The word girasol means “sunflower,” and in the summer, sunflowers line the outside of the blue and white painted building, which sits on Eddy Street just south of Notre Dame’s campus. As we arrived, a few minutes early (so that I could talk with Luz a bit about the restaurant before I got my food), I noted the small size of the building. There can’t be much room in there to eat, I thought to myself.

Indeed, when I walked in, I only saw one table, and a small row of barstools off to the side. The kitchen was connected to this eating area by a large window, through which I saw Luz working away, finishing up cooking our order. Her husband stood nearby at another frier, holding a spatula. She called out to me as I walked in, we talked for a short time about the restaurant as she bustled around. A few minutes later, I had my food in a plastic shopping bag, and was on my way out the door, ready to get home and enjoy my meal.

The pupusas of Girasol are definitely authentic; if you have lived in El Salvador, you will likely recognize them immediately. Luz gets her ingredients from Chicago, including the special cheese she calls her “secret” ingredient, and the pupusas are served with the traditional side dishes/toppings: cabbage slaw called curtido and a thin red salsa. When I opened up my bag, each of the ingredients was in a separate container, to preserve the food until I wanted to eat it. Of course I dug right in, one pupusa at a time, opening up the container, placing it on a plate and placing first a bit of the cabbage slaw on it and then pouring the salsa on top. It was delicious, and I could tell that each part of the meal was prepared in the pupuseria.

My meal, ready to be unpacked. The slaw is on the right, and the salsa on the left. I also got a horchata, visible in the cup at the top.

Luz Ferrufino told me that grew up on food like this, in her home country of El Salvador. On one wall is a painting of a farm house on red and green hills, which she said is similar to her home, where her mother taught her to cook. She told me a bit about her home, and told me she loved it. Her mother raised her and her siblings on the farm, raising farm animals. (2) But what brought her to this Indiana college town?

In 1981, a civil war began in her country, so she moved to America, initially to Virginia, where she met her husband, Martin, also an immigrant from El Salvador. They married and had four children in Maryland, but couldn’t turn turn down their oldest daughter, Elizabeth, when she got accepted to the University of Notre Dame.

When she came to America, she said that cooking just was natural for her, and could think of nothing else to do but to open up her pupuseria. And it has done well; Luz and her husband have been living in South Bend since 2005. Their daughter Elizabeth is a graduate now, and no longer lives at home, but Luz still enjoys running the restaurant, and can’t imagine giving it up anytime soon.

Luz belongs to the largest population of Central and South American people in America today, Salvadoran immigrants. The population is largest in California and Texas(3), but the Ferrufinos sought opportunity in the Midwest, and found a successful life. There are other a number of immigrants in South Bend, and Luz has formed a strong community with them, as well as the college students around town. In the 1980s, a large number of Salvadorans left the country as the country went into political upheaval.

The civil war that Luz Ferrufino left her home to escape is not the most well-documented event in modern times. In fact, it took me quite a bit of searching before I was able to learn about it in much detail. And it’s not like it was a small war: over 75,000 people died in a decade(4), between 1979 and 1989, and it wasn’t until 1991 that a new ruling party finally began to settle into place(5).

The few articles I found on the war were small paragraphs in Time or Newsweek from the time period, and there were only a few books relevant to the subject. Finally, after a detour through Wikipedia (usually a reliable source for the basics of a topic, and often a useful tool for finding related sources), I stumbled upon a short synopsis of the war in the US News & World Report, published near the end of the conflict in 1990.

It reports that the war began in October, 1979, when the military-led government was faced by a coalition of five guerrilla rebel groups. One of the inciting factors was the eleven distribution of income as a result of the coffee cash crop, which was run by only 2 percent of the people in the country(xxx). A combination of this, rising food prices, and fraudulent elections led to general unrest in the people, and after a military coup ousted their president in 1979, the United States saw an opportunity to remove a corrupt government and replace it with a more “democratic” one.

Those of you who have heard of Oscar Romero and his life may be familiar with what happened next. Romero was an archbishop in El Salvador, and he pleaded with the military and American government to stop this conflict before it grew too large, and urged militaries to disobey their orders to kill civilians. In 1980, he was assassinated, and a week later, his mourners were killed as well. From this point on, the country of El Salvador descended into a brutal state of chaos.

Both sides of the conflict used death squads and recruited child soldiers, and the conflict was supported by the United States government, which spent over a billion dollars in aid (xxx). The era was one of fear and political dispute, and the United States supported the war because they feared that a communist influence would win. Finally, in 1990, the United States pushed for peace, and an unstable peace appeared. This peace has lasted as well as any peace can so soon after a period of violence, and in modern times America is seeking to avoid more conflict, rather than encouraging it.

Today, Luz still has family in El Salvador, but she is not sure when she will visit again. It is interesting to reflect on her sense of identity, especially as an anthropologist. Having grown up in El Salvador, she definitely views herself as from Central America, and would be horribly offended if I questioned the “authenticity” of her food. But she readily admitted that she tones down the spiciness of her dishes to make them more palatable for the college students who visit and make up a large portion of her clientele. She has also now spent a large portion of her life in America, and her children went to school as Americans, so in that sense her identity is split. In addition, the country of El Salvador is very different than it was when she lived there, so in a sense she is displaced, having lost her home.

Throughout this class, we have looked at the history of Latin America through the distribution and spread of food. In my opinion, Luz has brought a bit of her home here with her, and it is preserved in the food she makes. The fact that someone from El Salvador can come to Indiana and have no trouble finding the necessary ingredients and tools to make the foods she ate when she was home says something very special about authenticity. Today, authenticity in ethnic food is less about where one is than it is the environment it is prepared. For example, I would definitely classify Girasol as an authentic El Salvadoran restaurant than I would a similar restaurant, owned by a person born in Indiana, who may have even visited El Salvador, but serves food in a restaurant decorated like a Fridays, and which also serves tacos and even chicken fingers, or has a kids menu.

Something about Girasol transported me to El Salvador in a way, whether it was the plain, spartan decoration of the pupuseria, or the accent of the woman who gave me change. Authenticity is a tricky word. To some, it means just that the food itself must be prepared a specific way.(6) But with that logic, very little food is prepared authentically, because the vast majority of people use modern tools such as stoves and electricity. To a strict “ethnic foodian” a true authentic meal can only be consumed in its country of origin. Luz does an excellent job of simulating this experience, and indeed, it is very common for places in Central America to serve purely takeaway food. The El Salvador which Luz Ferrufino left may not exist anymore, but, as it turns out, she brought a small bit of it with her to South Bend.

Sources:

1. Fouts, Sarah Bianchi. “From Pupusas to Chimichangas: Exploring the Ways in which Food Contributes to the Creation of a Pan-Latino Identity”. M.S. thesis, University of New Orleans, May 2012.

2. Ros, Pablo. “Eatery Offers Central American Food.” South Bend Tribune, September 4, 2007.http://articles.southbendtribune.com/2007-09-04/news/26765649_1_pupusas-el-salvador-pipil.

3. Landolt, Patricia. “Salvadoran Economic Transnationalism: Embedded Strategies for Household Maintenance, Immigrant Incorporation, and Entrepreneurial Expansion”. Global Networks 1, no. 3 (2001): 217-241. Wiley Online Library (14702266).

4. “Can Enemies Become Mortal Friends” US News & World Report 108 (1990): 46

5. “At Last, Hope for Peace in El Salvador” Newsweek, March 24, 1991. Accessed May 5, 2014. http://www.newsweek.com/last-hope-peace-el-salvador-201504.

6. Brester, Gary W. et al. “Salvadoran Consumption of Ethnic Foods in the United States”. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 2001.