Last class we talked about how one might design a digital edition of King Lear that doesn’t prioritize one version of the text above the other, that is readable as each individual version of the play, and that allows you to see variants when they occur. I think it’s theoretically impossible to get an edition of multiple witnesses of the text that does not even in the slightest privilege one version above another–one edition conceptually has to get put first, whether it’s the first listing in a drop-down menu of which version you’d like to look at, the first discussed in the introduction, or the default version to pop up when you click to look at the play. I think that no matter the attempt one makes to emphasize all the versions of the text equally, whatever the first option in that drop down list happens to be is still probably going to get more traffic than the other options. That said, I do think that there are some design practices that might minimize the prioritization of one edition over another. First of all, I think that a digital edition would need separate texts of each version that viewers could access independently of the others. They could hyperlink to each other at points of textual variance, but you’d need equally robust editions of each text of the play to create an unbiased edition. You could maybe even create a separate edition that acts somewhat like the one Arnaud had described in class–one where there are hyperlinks to look at alternate forms in other manuscripts.

I would probably handle footnotes or links to other recensions in an edition of King Lear similarly to how Susannah Fein’s online edition of the Harley 2253 manuscript handles footnotes. The footnotes are present and scrollable in a bar at the bottom of the page (I’ve linked to it here so that you can play around with it, because it’s difficult to see how it works from only a screenshot). There are hyperlinks in the text to any points of interest in the footnotes, and clicking on any of those hyperlinks takes you to the relevant point in the footnote bar, but leaves the main text where it’s at so that you can see them in parallel with each other:

Moreover, you can pull the footnote bar to wherever you like on the screen–the footnotes can take up most of the screen, or can be pulled out of the way if all you’re interested in is looking at the text. But I rather like this way of handling footnotes because it keeps the footnotes easily accessible at every point in your reading, doesn’t take you away from the main text when you click a footnote hyperlink, and you can choose how much of the screen you’d like it to take up. I think that for a project like the editing of King Lear, it’d be nice to have a multipurpose footnote bar–you could set it to show different things–the band of death, critical commentary on the passages, textual variants in other recensions, or even other witnesses of the same recension.

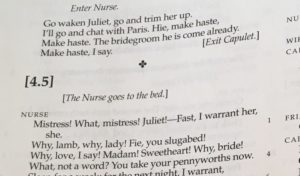

scene beginnings is interesting in conjunction with the way Bevington formats scene beginnings in the main body of the text. Although Bevington’s edition has text in each of the three lines of print dividing scene four from scene 5, the scene number is in a large font, making these three lines take up space equivalent to sic regular lines of the play. Accordingly, these three lines of print leave substantial negative space between scenes, accentuating the division between them. The small clover-shaped flourish at the end of scene four and the bold typeface for the scene number heighten this division. However, both the scene numbers and stage directions are offset with square brackets, which at once make it explicit that these additions are editorial interventions and perhaps also add a visual sense of uncertainty–although these are the traditional scene divisions, they’re tentatively put forward as the result of editorial tradition rather than words from Shakespeare’s pen. Like the location notes, the formatting of the scene change is at once designed to provide a clear division between the scenes, and to show that these subdivisions of the text and editorial interventions may not have been available to a contemporary reader of the play.

scene beginnings is interesting in conjunction with the way Bevington formats scene beginnings in the main body of the text. Although Bevington’s edition has text in each of the three lines of print dividing scene four from scene 5, the scene number is in a large font, making these three lines take up space equivalent to sic regular lines of the play. Accordingly, these three lines of print leave substantial negative space between scenes, accentuating the division between them. The small clover-shaped flourish at the end of scene four and the bold typeface for the scene number heighten this division. However, both the scene numbers and stage directions are offset with square brackets, which at once make it explicit that these additions are editorial interventions and perhaps also add a visual sense of uncertainty–although these are the traditional scene divisions, they’re tentatively put forward as the result of editorial tradition rather than words from Shakespeare’s pen. Like the location notes, the formatting of the scene change is at once designed to provide a clear division between the scenes, and to show that these subdivisions of the text and editorial interventions may not have been available to a contemporary reader of the play.

Mark Rose–“Pope vs Curll”

Rose’s first article summarizes the case that first established that authors have intellectual property rights over their works, and discusses both the effects of the court decision and how the case is situated within contemporary notions of the role of the author and of how the book trade works. Alexander Pope sued the bookseller Edmund Curll in June 1741 for publishing a series of letters exchanged between Pope and Dean Swift without Pope’s permission. Rose situates the case historically: the eighteenth century marks a period of transition from the patronage system to one more like our current system of literary production, and so he both emphasizes the legal precedent for the Pope suit and the way in which its ideological focus differs from current conceptions of copyright.

The legal precedent for Pope V. Curll is the 1710 Statute of Anne, which established that authors were the original owners of the rights to their works. It was based upon current patent law, and hence allowed authors and booksellers the right to their works for fourteen years, and twenty-one years for works that predated the statute. However, despite legal grounds for authorial copyright, Rose suggests that the participants in the case wouldn’t have viewed the case as a violation of property rights so much as a violation of propriety–it’s a publication of personal correspondence, which Pope argued was ungentlemanly to do without permission of both the authors and recipients of the letters. Pope claimed copyright over both the letters he wrote and the letters he received, however the case decided that he only had copyright over the letters he personally composed, not those written to him. This distinction is actually essential to our current notion of copyright because the case forced the judge to distinguish between the material property of the received letter, which belongs to the recipient, and the immaterial property of the text of the letter, which belongs to the author.

Rose, however, suggests that Pope’s motivations were somewhat mercenary for the time–he suggests that Pope tricked Curll into publishing his letters without authorization so that Pope could then publish an authorized version of his letters without seeming indecorous for doing so.

“The Author as Proprietor: Donaldson v. Becket and the Genealogy of Modern Authorship”

Rose’s second article details the circumstances behind the one of the next instrumental cases in the history of copyright law, Donaldson v. Becket, which centred around the question of whether or not authors owned intellectual rights to their books in perpetuity, and subsequently, whether the booksellers they transferred these rights to could keep them in perpetuity the same way they could keep an inherited property.

Rose argues that three cultural forces propel the development of copyright–mass-market publication, the valorization of original genius, and Locke’s idea that a person’s work is by right theirs. He argues that these concepts merge into the notion of the author as proprietor in the eighteenth century

Rose also argues that the emerging concept of copyright forced people to renegotiate the concepts of author and text. The proponents of perpetual copyright had to argue that the text itself of the author is akin to property in the author’s possession, which again differentiated between the physical manuscript the author owned and the intellectual property of the text itself. Conversely, those in favour of limited copyright argued that the ideas in a book were akin to those in patents, and should be legislated as such, while the proponents of eternal copyright argued that the essence of a literary work was inherent in the style and composition rather than simply mere ideas. The net result of the debate was that aspects of each group’s position became entrenched in the conception of what authorship and literature are–literary works were seen as property, and as intangible objects that included the sentiment and style of the author’s prose, yet the court’s ruling in favour of limited copyright also conceived of literary works, in a broad sense, as a sort of idea or social good that should be made available to the public after a span of time. In short, the debate forced a renegotiation of the idea of what literature and composition entail even as the case proceeded.

I thought Rose’s articles were lucid examinations of the relationship between copyright legislation and the popular conception of authorship and literary texts. Rose was at times repetitive, however, on the whole, I felt that the articles contextualized copyright legislation within the cultural moment of 18th century England well, and that they traced the development of the notion of the author as it was reflected on copyright rulings.