Why some of today’s musicians resist categorization

by Patrick Brogan

In today’s music, there is a trend of artists straying from traditional music genres. “Pop” music is often heard fused with hip-hop, R&B, or even country. Lil Nas X’s 2018 hit Old Town Road combined country and hip-hop in a way previously not seen to this extent in the mainstream, and it went on to set the record for the longest-ever run at #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100, remaining there for 19 weeks.

The song’s immense success stemmed from bringing together these two genres – and several others – in a seemingly silly but largely unifying way. The original song was so popular that it was remixed four times, with the likes of country’s Billy Ray Cyrus, EDM’s Diplo, trap’s Young Thug, and even K-pop’s BTS member RM joining on different iterations. The music video features famous artists and other celebrities donning over-the-top blinged-out rodeo-style outfits, all dancing and having a good time.

This kind of genre-blending is quite common. According to a 2019 article on the rise of genre-blurring music, “Of the 10 acts with the most on-demand streams [in 2019] in the U.S., six are known for blending styles,” says author Neil Shah. New rappers are singing, country artists are combining disco and psychedelia, jazz musicians are moving between a cappella, folk, and soul; completely redefining what it means to be a popular artist in the modern era. Despite the recency of these major successes, writer William Cahn claims that this crossing over of genres and styles reaches as far back as seven hundred years ago. The speed of progress for this movement increased greatly with the Internet and the newfound accessibility of music. Society as a whole is more diachronic today than ever before, and it has become easier and more desirable for listeners to explore diverse collections of songs that are right at their fingertips. Such access molds aesthetic preferences and allows artists to go beyond stylistic purity, granting them the opportunity to explore new regions of music-making.

Curious about the causes behind mixing genres, I conducted an interview with singer/songwriter Vincenzo Torsiello, a 22-year-old senior at the University of Notre Dame. Torsiello comes from a musical family: his mother does modern and flamenco dancing; his father began as a rock guitarist, studied classical music in college, and is now a highly skilled musician of many genres. “Everything I learned about music from a young age was just through my excitement about it and [my dad] telling me things.” Furthermore, he grew up speaking Spanish with his mother and was frequently surrounded by many different cultural and musical traditions.

Torsiello has released two 12-song albums, Jittersplit (2020) and Estesqueleto / Thiskeleton (2021), both an eclectic mix of songs spanning numerous genres. The first album was written during the pandemic. “When I released the music, [the distributor] CD Baby asked me for tags, and I was at a loss. So, what I did was – I tried to figure out what would be the most all-encompassing way to describe it,” Torsiello recounts. He found that the best ways to describe his music were power pop, alternative, piano rock, and singer/songwriter – all entirely distinct categories. After the release of his first album, Torsiello described in an Observer article some of his music as junk, a term he coined to capture the fusion of jazz and punk present in Jittersplit’s leading track.

Within his collective discography, Torsiello finds it difficult to pin down a succinct response to the type of music he makes. “People ask me this, and I try to tell them, ‘I’m a little all over the place.’” Not wanting to box himself in nor influence peoples’ opinions before listening, he says that he generally avoids genre markers, opting instead for listeners to make their own judgments. According to Torsiello, the more you listen to his music, the more you realize that it’s not what you may have originally expected. This is especially true for Estesqueleto / Thiskeleton, whose first six songs are in Spanish and the other six in English. Torsiello finds that a sense of authenticity stems from his decision to avoid labels. “If I tell you it’s rock, and you hit shuffle on my artist profile and ‘Family Tree’ comes on and you hear soft folk…” Torsiello began, going on to express his worries about preconceived notions of his music raising false expectations.

At the intersection of musical creativity and the actual success of a song, however, an interesting dilemma appears. Looking through his discography Torsiello declared ‘Coyunturas y Huesos’ – the fifth track on his second album – as his most autobiographical yet least streamed song in total. Furthermore, his Spotify for Artists profile showed that all of the six Spanish songs (also the ones most unlike all his recordings so far) were his least played, begging the question of the correlation between straying beyond genre norms and how a song performs for audiences.

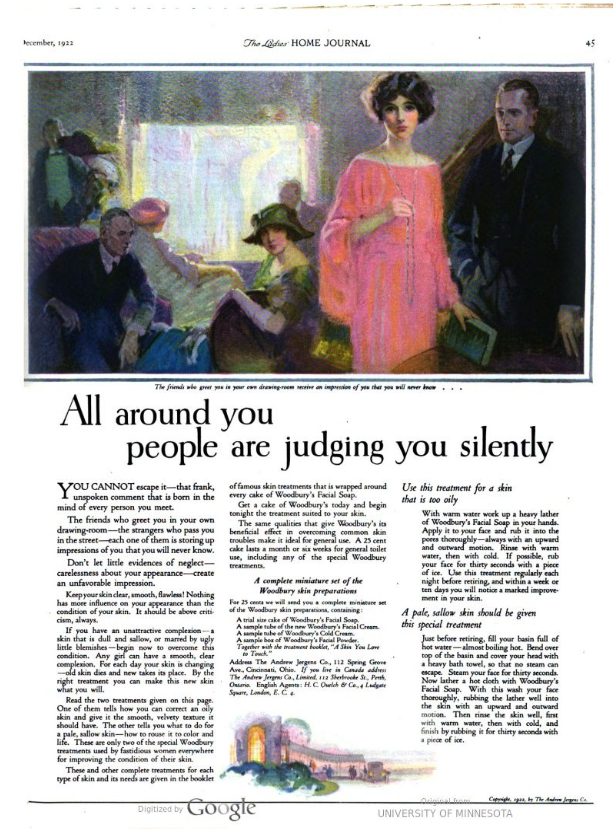

Cases such as that of Taylor Swift, who started her career only making country music, show that it is possible to achieve high levels of success in more than one market, as she is one of today’s biggest pop musicians. As researchers Yongren Shi, Yisook Lim, and Chan S. Suh have shown this level of inter-genre success is rare, however. They explored the relationship between boundary crossing and how the music performs or is perceived by audiences, finding “that genre-spanning musicians are more likely to receive lower rating on average compared to genre-specialist musicians in the market.” This pattern of penalty varies between genres, also. Genres with looser boundaries – those with more subcategories – tended to give straying artists a smaller negative impact than genres in which fewer variants exist.

Shi and her co-authors mapped the genres and subgenres as a network, visualizing the inter-genre relationships, showing which are close enough to move between without facing significant consequences.

The colors of the nodes display the parent genre, the connections display which genres are cross-listed by musicians, and the greater thicknesses/shorter distances between subgenres represent an increased frequency of shared genres in songs. In some ways, this mapping can be seen as a sort of roadway for current artists: although it’s possible to move from one side or one color to another, it may be very difficult. Yet musicians continue to chart their own journeys, creating new genres, genre-blends, and other bodies of work that push the envelope of what exists in the musical world.

For now, it seems as though big genres will be here to stay. Though many of today’s hits do not fit within the typical norms of one genre alone, access to this kind of catalog gives artists and listeners alike the avenues through which music is created and distributed. A few breakout hits give a preview of what the distant future may look like, but until then, music’s mainstream still exists in only a handful of channels; with only some creative individuals capable of moving away from these norms.