BBC, 23 January 2020

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESIn August 2017, a deadly crackdown by Myanmar’s army on Rohingya Muslims sent hundreds of thousands fleeing across the border into Bangladesh.

They risked everything to escape by sea or on foot a military offensive which the United Nations later described as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

In January 2020, the UN’s top court ordered the Buddhist-majority country to take measures to protect members of its Rohingya community from genocide.

But the army in Myanmar (formerly Burma) has said it was fighting Rohingya militants and denies targeting civilians. The country’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi, once a human rights icon, has repeatedly denied allegations of genocide.

Who are the Rohingya?

Described by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as “one of, if not the, most discriminated people in the world”, the Rohingya are one of Myanmar’s many ethnic minorities.

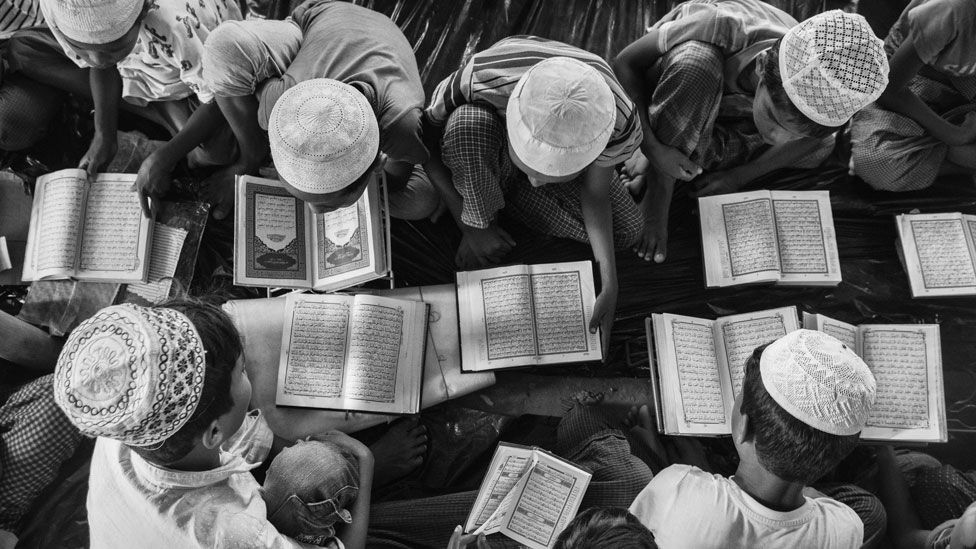

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe Rohingya, who numbered around one million in Myanmar at the start of 2017, are one of the many ethnic minorities in the country. Rohingya Muslims represent the largest percentage of Muslims in Myanmar, with the majority living in Rakhine state.

They have their own language and culture and say they are descendants of Arab traders and other groups who have been in the region for generations.

But the government of Myanmar, a predominantly Buddhist country, denies the Rohingya citizenship and even excluded them from the 2014 census, refusing to recognise them as a people.

It sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

Since the 1970s, Rohingya have migrated across the region in significant numbers. Estimates of their numbers are often much higher than official figures.

In the last few years, before the latest crisis, thousands of Rohingya made perilous journeys out of Myanmar to escape communal violence or alleged abuses by the security forces.

Why did they flee their homes?

The exodus began on 25 August 2017 after Rohingya Arsa militants launched deadly attacks on more than 30 police posts.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESRohingyas arriving in Bangladesh said they fled after troops, backed by local Buddhist mobs, responded by burning their villages and attacking and killing civilians.

At least 6,700 Rohingya, including at least 730 children under the age of five, were killed in the month after the violence broke out, according to medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

Amnesty International says the Myanmar military also raped and abused Rohingya women and girls.

The government, which puts the number of dead at 400, claims that “clearance operations” against the militants ended on 5 September, but BBC correspondents have seen evidence that they continued after that date.

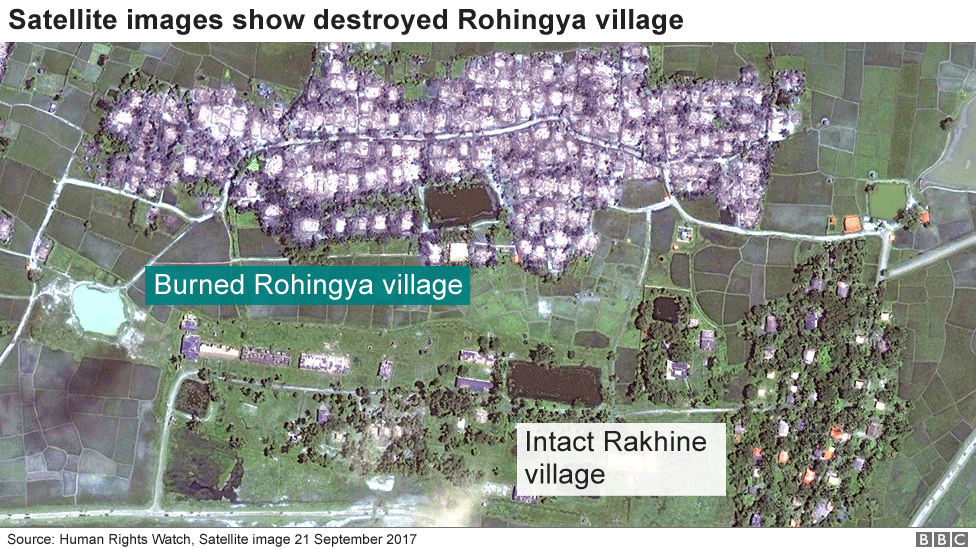

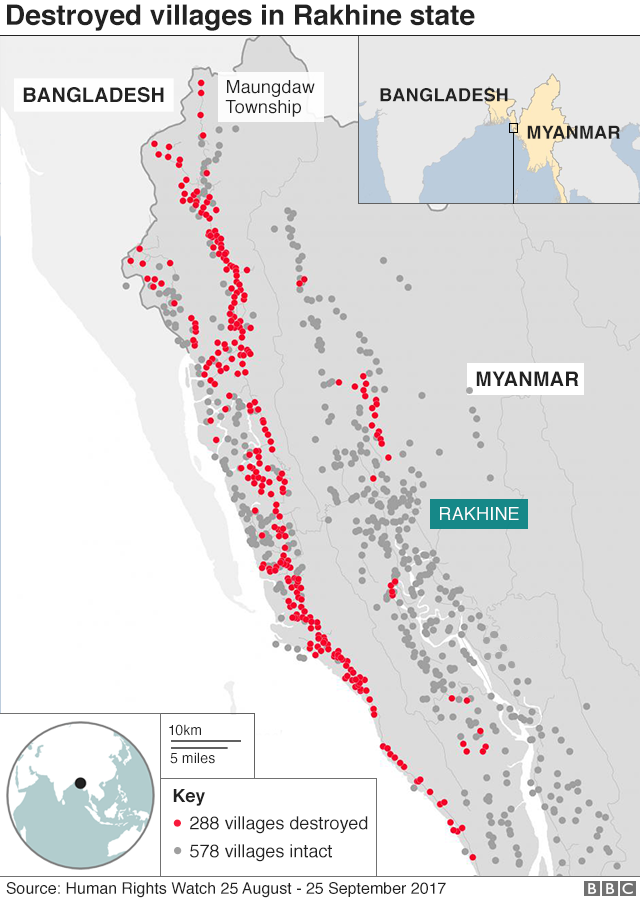

At least 288 villages were partially or totally destroyed by fire in northern Rakhine state after August 2017, according to analysis of satellite imagery by Human Rights Watch.

The imagery shows many areas where Rohingya villages were reduced to smouldering rubble, while nearby ethnic Rakhine villages were left intact.

Human Rights Watch say most damage occurred in Maungdaw Township, between 25 August and 25 September 2017 – with many villages destroyed after 5 September, when Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, said security force operations had ended.

What has the international response been?

A report published by UN investigators in August 2018 accused Myanmar’s military of carrying out mass killings and rapes with “genocidal intent”.

The ICJ case, lodged by the small Muslim-majority nation of The Gambia, in West Africa, on behalf of dozens of other Muslim countries, called for emergency measures to be taken against the Myanmar military, known as Tatmadaw, until a fuller investigation could be launched.

Aung San Suu Kyi rejected allegations of genocide when she appeared at the court in December 2019.

But in January 2020, the court’s initial ruling ordered Myanmar to take emergency measures to protect the Rohingya from being persecuted and killed.

While the ICJ only rules on disputes between states, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has the authority to try individuals accused of war crimes or crimes against humanity. The body approved a full investigation into the case of the Rohingya in Myanmar in November.

Although Myanmar itself is not a member of the court, the ICC ruled it had jurisdiction in the case because Bangladesh, where victims fled to, is a member.

Myanmar has long denied carrying out genocide and says it is carrying out its own investigations into the events of 2017. The country’s Independent Commission of Enquiry (ICOE) admitted that members of the security forces may have carried out “war crimes, serious human rights violations, and violations of domestic law”, but claimed there was no evidence of genocide.

Its full report has not yet been released, but questions have been raised.

What is happening to the Rohingya now?

With more than half a million Rohingya believed to still be living in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine province, UN investigators have warned there is a “serious risk that genocidal actions may occur or recur”.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe situation that led to “killings, rapes and gang rapes, torture, forced displacement and other grave rights violations” in 2017 remained unchanged, the investigators said in September, blaming a lack of accountability and Myanmar’s failure to fully investigate allegations or criminalise genocide.

Rakhine province itself is the site of an ongoing conflict between the army and rebels from the Buddhist-majority Rakhine ethnic group.

What about the refugees?

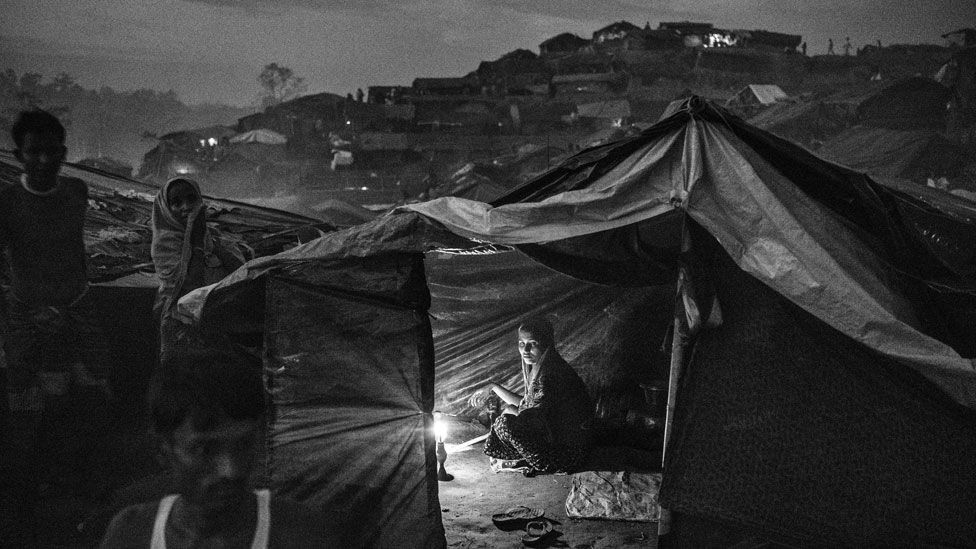

The massive numbers of refugees who fled to Bangladesh in 2017 joined hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who had fled Myanmar in previous years.

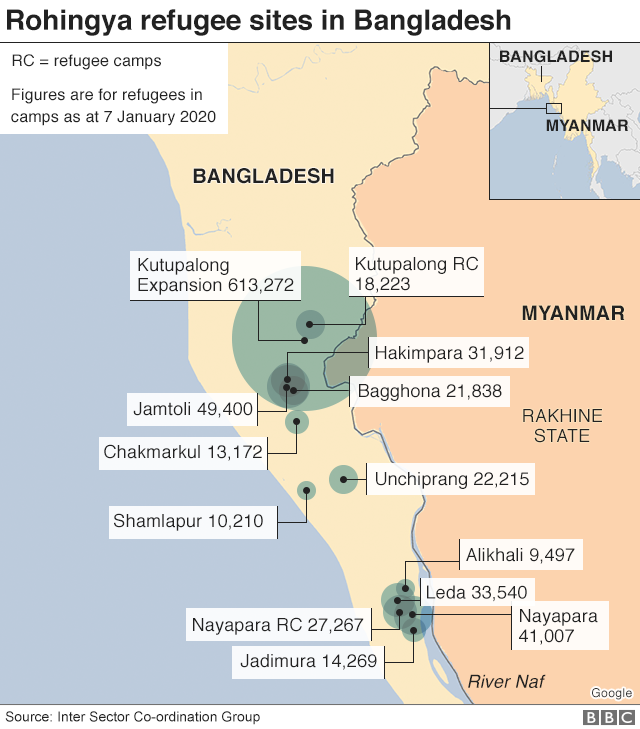

Kutupalong, the largest refugee settlement in the world according to UNHCR, is home to more than 600,000 refugees alone.

But in March 2019, Bangladesh announced it would no longer accept Rohingya fleeing Myanmar.

While an agreement for the return of refugees was reached in early 2018, none returned. They said they would not consider going back to Myanmar unless they were given guarantees they would be given citizenship.

And as a BBC investigation showed, even those considering returning in the future may not be able to, with villages destroyed to make way for government facilities.