PART V

We now move our way toward the end of my story about the nation state. I devote this final section of our course to the meaning of a fuzzy term–Globalization–and its relationship to the Nation State. We will considere some more themes related to the post-colonial world and then conclude by reflecting on all of the themes in this course.

The term “globalization” has become a terrible a cliche. Myriad universities and corporations have rushed to define themselves as “global” enterprises. I am uncomfortable with the concept because it is so vague. Morever, the conditions the term is supposed to capture are hardly new. If we define globalization as a massive expansion in contacts and communications among peoples, greater interdependence, and the spread of new technologies, I’m afraid that Genghis Khan (1162-1227 AD) and Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) would be offended by being excluded.

This is not to say that “globalization” has no meaning. Consider this manifestation of globalization and the coming together of the American fabric: The Funeral of Knut Rockne and the American Experience

To avoid the problem of stretching the concept to the point where it is useless, I will simply focus on a few contemporary ways in which the world has become, as they say, “a smaller place.” I will begin with two popular mythologies about where we are and where we are going:

Global liberalism is rational

Global violence is irrational

In my final lecture, you will see that we have returned to the questions I raised on the first day of our course.

38. LECTURE: Wednesday, November 29

Myth #1: “The spread of global liberalism is rational.” No, it’s not always rational! Its effects are often counterproductive and destabilizing.

Assumption: People in the western world like to view themselves as the telos (or inevitable destination) of humanity. In particular, they have a “evangelical” view of their mission: they associate the idea of “globalization” with the spread of their values. However, it is sheer mythology to imagine that these values are uniformly appropriate for the rest of the world. Ironically, even John Stuart Mill’s classical conception of “liberalism” has become ossified. As Weber would say, contemporary liberalism, or what goes by that name, is locked into an “iron cage.”

Assignments: So, is globalization good or bad? Or should we frame the question differently?

Globalization and the Mythology of Coca-Cola WATCH

Benjamin Barber, “Jihad vs. McWorld” PRINT AND READ

John Rapley: “The New Middle Ages,” Foreign Affairs (May-June 2006) Go to the many online sources in the Hesburgh collection HERE and look for Vol. 85, Issue 3. PRINT AND READ

Gordon Adams, “The French Colonialist’s Global Comeuppance,” Foreign Policy, January 2015: PRINT AND READ

39. DISCUSSION: Friday, December 1.

The focus of this section relates to the long and winding road back to where we began which I first introduced you to the nation-state. The first two articles are essential reading for my final lectures.

Has political history, as we have known it come to an end (see Fukuyama), or are we destined to experience serious trials in the future (see Brownstein)?

For this discussion, read only Fukuyama’s Introduction and Sections 3 and 4. However, read them very closely. Fukuyama’s argument is complex. Plus, there are aspects of it that I find problematic. Finally, in interpreting the essay, it’s helpful to know that Fukuyama was a student of Samuel Huntington.

Francis Fukuyama: “End of History,” National Interest, Summer 1989 PRINT AND READ

Ronald Brownstein, “Why the US ‘does not get to assume that it lasts forever'” PRINT AND READ

.

Paragraph assignment: Let’s say Fukuyama is wrong and the liberal democratic regimes, like the US, are not the end of history. What is the most likely type of regime that will replace them, and why?

.

Your final essay assignment is HERE

.

40. LECTURE: Monday, December 4

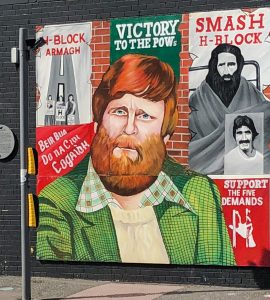

Myth #2: “Global violence is irrational.” No, it’s often frighteningly rational!

Reflections on one weapon of the weak: Terrorism and the rational roots of inhumanity.

Osama bin Laden: “Transcript of Speech,” Al Jazeera.com, Nov. 1, 2004 READ

“Attacks by White Extremists Are Growing. So Are Their Connections,” New York Times, April 3, 2019 READ

Julia Carrie Wong, “The physics professor who says online extremists act like curdled milk,” The Guardian, August 23, 2019 READ

.

41. LECTURE: Wednesday, December 6

41. LECTURE: Wednesday, December 6

Reflections on liberal democracy: My bias for hope

Today’s Assumption: It’s hard to be optimistic about the chances for global liberalism, especially as we struggle with the devastating consequences of a pandemic. But it’s reasonable to be hopeful. It’s also necessary.

Assignments:

Consider this hopeful view from three decades ago. Once again, we hear from Samuel Huntington: “Democracy’s Third Wave,” Journal of Democracy, Spring 1991. READ (just get a general sense)

Paul Tullis, “How Geert Wilders Won”: PRINT AND READ

The fairly hopeful view from today: Cas Mudde, “It’s fashionable to say that democracies are dying,” The Guardian, January 28, 2018 PRINT AND READ

A hopeful analogy from the business world: Knowledge@Wharton, “Lew Gerstner’s turnaround tales at IBM,” READ

And yet there’s still a lot of work for us to do. See this Freedom House report on the state of democracy in the US: READ (just get a general sense)

(just get a general sense)

Vaclav Havel, “Never Hope against Hope” RE-READ