We begin with a novel human invention: The Nation-State!

Over the past couple centuries, people in many–but not all– countries have grown accustomed to living in the era of the Modern Nation-State. In this opening section of our course, I shall outline the defining aspects of this unique human invention. I shall also outline the characteristics of the particular expression of this state that most of us have experienced throughout our lives and from which we have profited immensely: Liberal Democracy. I will draw a connection between two perspectives we all share in common: “modernity” and “liberalism.” At this early point in the semester, we will deal with several abstract concepts, or “ideal types.” These abstractions will become real to you when we explore the origins and evolution of a distinct type of state: the Liberal Nation-State.

In class today, I mentioned the Suwalki gap, the 40-mile long corridor separating the isolated Russian naval port of Kaliningrad and Belarus (and hence Russia) as an example of contested versions of the nation-state. Here is a fresh article that examines different views of the likelihood of military conflict between NATO and Russia over this gap. I found the article reassuring. However, my friends in two countries that I have visited–Georgia and Ukraine–didn’t think Russia would invade their territory. See here.

To get us moving, I have created a reading assignment for your first discussion section this Friday.

1. LECTURE: Wednesday, August 23

The making of the Modern Nation-State and the indeterminate nature of human choice.

Today’s Assumption: The Modern Nation-State is distinguished by the underlying idea that one can bring together different peoples and contending identities under the rubric of a common community. This state form represents a novel way of organizing human beings.

Nation-states did not exist until roughly the 18th century. The emergence was slow, unpredictable, and always violent. For example, one can’t legitimately speak of the emergence of a “Germany” or an “Italy” until the second half of the 19th century. Many people died fighting against the creation of nation-states throughout the world, and even after they were formed, they were unhappy nation-states for a long time.

To be clear, not all states are Nation-States. And, not all peoples want to live together. Consider the tragic consequences of our failed experiment in nation-building in in a place that is not a nation-state—Afghanistan. If only our politicians had been better historians, they would have understood what they were getting into, just like the British and the Russians had failed to understand earlier. And then, we would appreciate our contribution to the devastating circumstances that we left behind. This is not to say that we didn’t do good things. It is simply to say that we–and especially we Americans–should have understood what it means to attempt to impose one model of political organization on another.

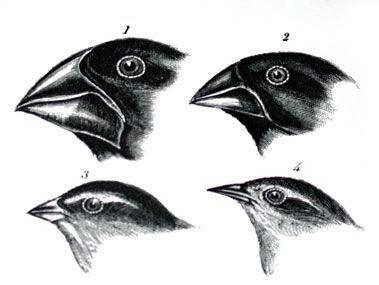

To understand the origins of the nation-state, it is essential to reflect upon the nature of political change. Watch the video about natural evolution below and reflect upon how it gives us insight into the uniqueness of the nation-state.

The nature of historical change as seen by a paleontologist. A fabulous thinker, Steven Jay Gould, offers an approach to studying fundamental change that I find totally convincing—evolutionary theory. Watch at least the first 6 minutes of this stimulating video: WATCH As you listen to Gould, ask yourself how his arguments about both human evolution, “punctuated equilibrium” (what does this concept mean?), and the extinction of dinosaurs can be applied to the evolution of political ideas and institutions.

The nature of historical change as seen by a paleontologist. A fabulous thinker, Steven Jay Gould, offers an approach to studying fundamental change that I find totally convincing—evolutionary theory. Watch at least the first 6 minutes of this stimulating video: WATCH As you listen to Gould, ask yourself how his arguments about both human evolution, “punctuated equilibrium” (what does this concept mean?), and the extinction of dinosaurs can be applied to the evolution of political ideas and institutions.Are we currently living in a state of punctuated equilibrium? I think so.

Look ahead to your Friday discussion section. You have a paragraph assignment.

2. DISCUSSION SECTION: Friday, August 25

This discussion section is about the implications of living in a modern nation-state. It will also relate to Monday’s lecture about a particular form of modern politics–the liberal nation-state.

Today, you will discuss what it means to be a real American (or a real member of any political community).

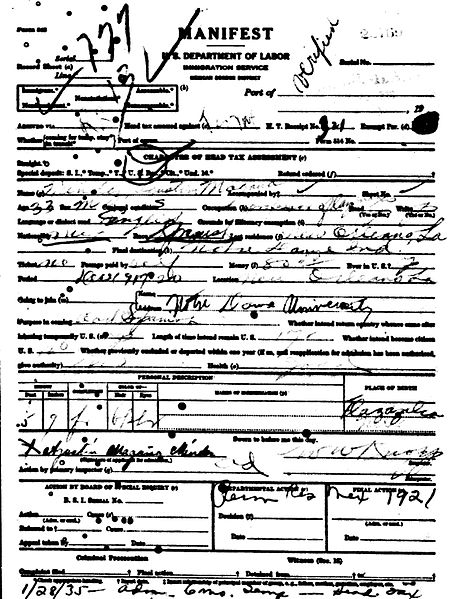

How do we decide who is fit to belong in the United States? How do we decide who does not? Assuming you are an American citizen–and I realize that some you are not–how did you acquire this title? Should every American do more to reasonably be called a citizen? If so, what? Finally, how are Americans doing with those who becomes their fellow citizens?

If you are from another country, such as Paraguay, China, Chile, Canada, or Spain (Catalonia), how easy is it to become a citizen in your home? Is it easier or harder than in the US?

Here’s a classic statement: Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus,” a plaque on America’s Statue of Liberty: READ

Readings:

Primary Reading #1: Samuel Huntington, “The Hispanic Challenge” (Foreign Policy): PRINT AND READ

Huntington was a preeminent political scientist. Note his incredible prediction on p. 14. This is an important and controversial article.

Primary Reading #2: Amanda Gorman, “The Hill We Climb”

Read Gorman’s poem carefully. Although it isn’t directly linked to Huntington’s argument, the implications are certainly there: Read, Print, and Listen

Finally, consider this: What is an American Car? READ Why would I ask you to read this article in the context of our topic?

Here is your writing assignment: Write a one-paragraph (no more!) response to the following question: “What is the single, most important requirement for being a ‘true American’.” You may only choose one requirement. The point of your paragraph is to persuade the reader why it is the single, most important factor.

You should send your TA the one-paragraph response by 5:00 on Thursday. Your TA will provide you with instructions about how to send this as a Google document. This Thursday rule will be apply to the submission of assignments for all of our upcoming discussion sections. All of your paragraphs should be typed and double-spaced (12 point font). No handwriting.

Both your TA and I will be happy to talk with you about this assignment or any future assignments. Simply visit us.

3. LECTURE: Monday, August 28

Reflections on what it means for us to live in modern times.

Today’s Assumption: Whether we like it or not, we live in a modern society. By this statement, I mean that we share certain conceptions of truth and ideas about how to organize our lives. These ideas differ fundamentally from those held by other societies in the world, especially the most traditional societies.

Today, I will outline four essential characteristics of the “ideal-typical” modern world.

An essential part of being modern is agreement on facts. As a result of our capacity to reason, we pursue factual knowledge and build theories by using the scientific method (even though we don’t always recognize that this is what we are doing).

This is not to say that this approach to knowing is necessarily a good thing. Or that it represents all of the possible activities that are open to us. The acceptance of a factual claim (e.g., a heliocentric model of our solar system) does not prevent us from holding a religious faith (e.g., the existence of God). The believer’s faith in God may be just as true as factual knowledge. Indeed, a believer may justifiably regard his or her faith to be the quintessential expression of truth-seeking. Throughout much of its history, the Catholic Church has maintained that there is no contradiction between the pursuit of scientific truth (reason) and faith in God—these truth claims are simply different forms of knowing.

Here are two articles that relate to my lecture. Ask yourself why they have to do with today’s topic.

Jen Christensen, “The Most Accurate Clock in the World is Redefining the Second” READ What can a mechanical clock tell you about the origins of a modern society?

lan Burdick, “Some Good News, and a Hard Truth about Science,” New York Times, November 18, 2018 READ

4. LECTURE: Wednesday, August 30

Today, I will lecture about a revolutionary political invention, the Liberal Nation-state. Liberalism is a specific set of principles according to which some human beings have organized their relations in modern times. However, it is not the only expression of modern politics. As we shall see later in this course, Fascism and Leninism are also forms of modern politics. As we look into the future , we can be sure that there will be seemingly self-evident political identities that are not liberal at all. We are wrestling with the defense of liberal political identities right now.

Today’s Assumption: We are all Liberals! Or at least those of us who come from liberal-democratic states. However, this is no cause for alarm for political conservatives, at least not for moderates. In making this claim, I do not mean that we are all “liberals” in terms of our political affiliation. For example, moderate Democratic politicians and moderate Republican politicians alike adhere to classical liberal principles. They simply have different conceptions about how to solve concrete problems. Making concrete political decisions on a daily basis is necessarily complex—just like making good wine. Reasonable policymakers in a well-functioning political order will naturally disagree about what constitutes good policy. As John Stuart Mill advises us: this is a good thing.

Thus, when I use the term “liberal,” I am referring to classical liberalism, a conception of political order that was invented–not discovered–by people like John Locke, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill.

Assignment: Read Chapter II, “On the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” in John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1869): PRINT AND READ

Then, listen to musician and philosopher Frank Zappa talk about freedom of speech HERE Do you agree with Zappa? If not, where should we draw the line between legitimate and illegitimate free speech in a Liberal society? Or should there be a dividing line at all?

Read ahead for the discussion readings and paragraph assignment for Friday.

Optional reading, which relates directly to the emergence of the US as a liberal nation-state:

Abraham Lincoln invents the liberal nation-state: HERE

5. DISCUSSION SECTION: Friday, September 1

John Stuart Mill’s affirmation of rigorous debate over diverse conceptions of true is a core theoretical foundation of classical liberalism. Yet, the application of this principle to the real world is always more difficult than it seems. This is particularly true in higher education, where the adoption of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” programs and principles has recently led to bitter battles over what should–and what should not–be taught in the classroom. One side argues that the application of such principles is essential for the pursuit of the whole truth. The other side argues that this practice is nothing but a cover for a “woke ideology” that actually stifles the liberal pursuit of truth.

Over this past summer, the New York Times has given representatives of both sides numerous opportunities to defend their views (and attack their critics) on its Op-Ed Page.

Here are two noteworthy examples:

Christopher Rufo, “D.E.I” programs are getting in the way of liberal education.” READ AND PRINT. Rufo is a key advisor to Florida Governor Ron DeSantis on higher education policy.

Jamelle Bouie, “Ron DeSantis and the State Where History Goes to Die” READ AND PRINT

Who is right? Rufo or Bouie? In preparing for your discussion section, identify each author’s key points. Ask yourself why people might reasonably disagree over what should—or should not—be included in a university classroom, regardless of whether it is the University of Florida or Notre Dame. Is there room for compromise on some or even all of the issues?

Paragraph assignment:

Write a single paragraph in which you identify the strongest points in each author’s opinion pieces. Then, state why one author is right and the other is wrong. No waffling. You must defend one side over the other.