A Feminist Decolonial Critique of Liberation Theology and Fratelli tutti

Elizabeth Boyle

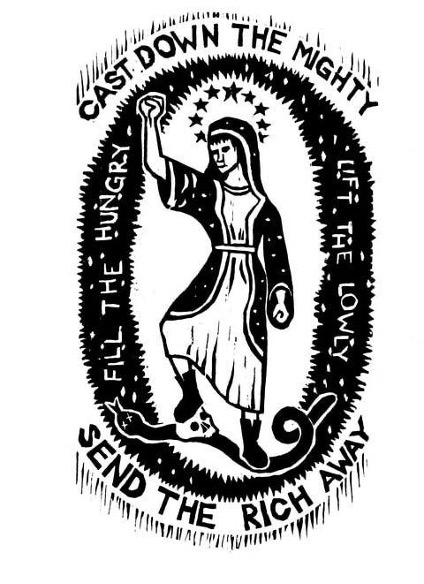

He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty.

Luke 1:46-55

The scandal of poverty cannot be addressed by promoting strategies of containment that only tranquilize the poor and render them tame and inoffensive.

Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti

The Magnificat is a popular Catholic canticle from the Gospel of Luke when Mary visits her cousin Elizabeth, both of them miraculously pregnant. This “Song of Mary” used in Church services, Vespers, and Liturgy of the Hours has strong implications outside the walls of the church. The canticle emphasizes the abilities of God to lift God’s people out of oppression. Mary believes in a God who will “exalt the poor and the lowly”[1], further explicating a larger general theme of the Gospel: God’s preferential option for the poor. When read through the lens of the exhortation of Mary, it becomes clear that Catholicism is deeply rooted in a commitment to uplift the marginalized and overturn oppressive systems. The Magnificat is an example of a theological practice rooted in the preferential option for the poor, a critical component of liberation theology.

The Magnificat has been reconceptualized by liberation theologians to galvanize support for the most marginalized, reminding Catholics and others that God’s existence is always rooted in uplifting the poor and ridding societies of oppression. The field of liberation theology has, in the past six decades, expanded into sub-fields of Black, feminist, and eco-feminist liberation theologies, among other areas. It has captured the attention of Pope Francis, a frequent critic of what he calls the ‘scandal of poverty’. Most recently, however, liberation theology has emerged as a potential decolonial option for the Catholic Church: a theological tool that may finally force the Church to reconcile its colonial past and take material steps to redress past harm, apologize for it, and center the voices and work of decolonial thinkers. The recent encyclical from Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, creates an important opening for this decolonial turn in the Catholic Church because it is deeply rooted in liberation theology.

I posit liberation theology, as woven into Fratelli Tutti, offers an important opening for a decolonial turn in the Catholic Church, but must go further and critically examine and incorporate feminist, queer, and Black theological insights to be truly liberatory and decolonial. I will use Fratelli Tutti, as well as critical liberation theology texts, feminist liberation theology, and decolonial scholarship to further this thesis. In Section I, I introduce key theological concepts of liberation theology as espoused by first generation liberation theologians as well as discuss how liberation theology can be considered a decolonial theory. In Section II, I introduce feminist decolonial critiques of liberation theology from Maria Pilar Aquino, Mayra Rivera Rivera, and Maria Jose F. Rosado Nunes alongside of other feminist and decolonial critiques to show how these critiques strengthen liberation theology and expose the gaps left by first generation liberation theologians. In Section III, I share excerpts from Fratelli Tutti that are rooted in liberation theology while also applying a feminist decolonial liberation theology critique to those quotes in the effort to strengthen the work of the encyclical. Finally, in Section IV I conclude by responding to counterarguments and reiterate the main argument that if Fratelli Tutti was written from a feminist, theological, decolonial perspective then it would have strengthened the encyclical and signaled a true decolonial turn in the Catholic Church.

I.

Liberation theology took hold in 1960s Latin America against the backdrop of economic oppression and increasing political tensions.[2] The “founder” of liberation theology, Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez, describes it as a “critical reflection on historical praxis in the light of the Word [of God].”[3] Gutiérrez presents liberation theology as a relation between biblical salvation and the historical process of human liberation. He offers this theology as an alternative path to achieving liberation for the oppressed. Gutiérrez argues that because Latin America grew out of economic dependence on other nations, its liberation is only possible when movements overturn existing colonial structures–a very Fanonian approach to liberation.[4]

Dependency theory was heavily influential on liberation theology and thus Gutiérrez focuses on “poverty” as material poverty (which he viewed as a “scandalous condition”,[5] language that Pope Francis uses today) that derails a person’s life by limiting them from attaining necessary resources as well as spiritual peace. Liberation theologians view God’s commitment to the poor not as an option but as a necessity; the only way to understand theology and God’s existence in the world is through the experiences of the poor. Gutiérrez draws on the work of Paulo Freire, Karl Marx, and Ernesto “Che” Guevara to emphasize the process of liberation and liberation theology is more than just overcoming economic, social, and political dependence: it means “to see the becoming of humankind as a process of human emancipation in history…It is to seek the building up of a new humanity.”[6]

The work of the first generation liberation theologians such as Gutiérrez was critical for setting into motion what could be considered the start of the modern decolonial theory in the Catholic Church. Scholars such as Joseph Drexler-Dreis, Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Reinerio Arce-Valentín, among others have extensively traced potential implications of liberation theology as a decolonial method. Decolonial thought, and the decolonial turn, is a call to the concrete politics of liberation. This decolonial approach is something scholars in the West are swiftly shifting their focus towards, however, it has been practiced by Indigenous cultures since it operated as a form of active resistance to early colonization.[7] Reinerio Arce-Valentín notes liberation theology has made inroads towards replicating Indigenous decolonial approaches, which is just a reflection of a broader eagerness to engage with the history of Latin American theological thought and reflection.

In reflecting on why he believes liberation theology can function as a decolonial option, Arce-Valentín states:

The decolonial approach stems from a different intellectual genealogy, revealing the complex interactions between race, ethnic roots, gender, and religiosity together with current social, political, and economic elements. It follows a critical strategy against coloniality in the search for our own identity, both as part of our traditions and of the current resistance to contemporary neocolonial attempts; always looking, now more than ever, for the construction of our free and sovereign America.[8]

Liberation theology offers this “different intellectual genealogy” because it is deeply rooted in the point of view of those who were the “victims of modernity”[9]; the colonized, the poor. As Luis Martinez Andrade discusses, Fr. Gutiérrez always believed it was critical to give voice to the voiceless and to center those who have largely been “absent from history” because their lived experiences are rendered invisible by the processes of modernity and coloniality.[10]

II.

Scholars trace how liberation theology both upholds the decolonial turn as well as inspires a greater discussion on liberation and decoloniality within the Church and political structures in Latin America. Though liberation theology seems to fit as a perfect decolonial option from the perceptive of many of the aforementioned scholars, there is a glaring gap in the field of liberation theology: a feminist perspective. Early decolonial theory often either failed to engage with sex/gender/sexuality, or, like Anibal Quijano, focused primarily on sex rather than gender as a facet of exploitation for economic (re)productivity. María Lugones pushes back against Quijano’s work, saying it frames sex and gender in a binary Eurocentric lens.[11] Lugones introduces the concept of the “coloniality of gender” because she believes Quijano and others’ use of colonial co-constitution of gender as reproduced by patriarchal societies may further erase and oppress colonized and indigenous women.

The work of feminist and womanist theologians is critical in strengthening the field of liberation theology and theology writ-large. Pilar Aquino argues a feminist critical analysis of patriarchal gender relations is the best point of entry for analyzing a society because it highlights primary power relationships that have historically been rendered invisible.[12] She notes that over the past three decades there has been a blossoming relationship between liberation theologians and feminist movements because both are rooted in critical theories undergirded in a deep understanding of the Gospel message as attentive to the modern-day, lived faith experience of the individual person, with a particular focus on the experience of the most marginalized.[13] A feminist theological discourse, as defined by Pilar Aquino, is one that operates as a critical reflection on the lived experiences of God as made manifest in the struggles to combat poverty and violence and the attempt to promote justice and integrity for all.[14] In drawing particular attention to Latin American feminist theologians like herself, Pilar Aquino says they seek to “collect, interpret, and shed light on the questions and concerns of the socioecclesial groups that perceive the dehumanizing character of sexism in society, church, and theology.”[15]

It is critical to understand, however, that Latin American feminist theologies existed before liberation theology came into being. Indigenous women have always had to confront violent invasion and colonization using the resources available to them at the time. Pilar Aquino notes that even though most resources were denied women, historically many movements of campesina, Indigenous, Black and mestiza women were able to pursue liberatory practices in Latin America.[16] Latin American women have always had to fight for their existence and their visibility, thus their very theologies are deeply rooted in a desire to liberate those who face oppression.

A feminist liberation theology gives credence and precedence to women’s embodied conditions and uses their marginalization as the starting point of their theological work. Latin American feminist liberation theology took hold because, as Rosado Nunes notes, liberation theology did not significantly deal with the oppression of women.[17] Feminist Latin American liberation theology in particular locates itself in the “world of poor and oppressed women” who represent the majority of Latin America society.[18] As Mayra Rivera Rivera posits, a decolonial epistemology must deeply interrogate the production of knowledge as both an academic and physical process. Rivera argues that first generation liberation theology neglects “rebellious, unruly, queer bodies.”[19] She believes liberation theology loses sight of the unseen, the neglected bodies, the bodies rendered “other” by the process of colonization. Since first generation liberation thinking is dominated by men, there is no deep discussion of gender versus sexuality. First generation decolonial thinking does not address these topics until later interventions. Rivera references the work of Lugones and urges Latina critiques to address the differences in the constructions of gender and sexuality, specifically acknowledging how the dark side of the gender binary has led to the creation of both a repressive, Victorian image of women as well as a hyper-sexualized image of Latina women.[20]

For Rivera, understanding the physical and the way that women inhabit their bodies is critical to understanding God’s manifestation in our world. To do so, she proposes a polydox theology which engages an earthy sense of doxa. A polydox theology requires deep attention and responsiveness to the existence of God manifested in our physical world, encouraging a more immersive, environmentally-centered theological approach that demands action. She refers to polydox theology as: “A theological attitude that relates to thought, opinion, and praise, but also, more deeply, to the world’s provocations and demands as well as to our affective responses to it.”[21] She sees a polydox theology as uniquely attuned to respond to the cries of terror from the colonized and as applying a creative lens that recognizes the manifestation of God’s glory in those things and people that are rendered invisible.[22]

Liberation theology sees God made manifest in the cries of the hungry and the shouts of the poor and Rivera believes that this means we need to take an ontological approach to understanding bodies within the Catholic faith. She argues that when we understand how faith is rooted in our inhabited bodies and socially constructed labels we put upon them, we can better understand how God’s revelation manifests in our flesh; in our cries and longings. Her feminist polydox theology is critical because it opens spaces for “indeterminacy and wonder, dis-enclosing theology, to experience glory in our perennially unfinished and redeemable world.”[23] In other words, polydox theology, more so than liberation theology, is able to actually transcend colonial structures and violence because it is a deeply intersectional theological practice that is rooted in the lived physical experiences of those who are always left to be forgotten.

III.

It is apparent that the impactful work of feminist liberation theologians is crucial to achieving a decolonial turn in the Catholic Church. In October of 2020 Pope Francis released his encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, which translates to “All Brothers”. Encyclicals are the second most important document published by the Pope and signify the issue discussed therein is of high importance. Over the past few years Pope Francis has increasingly spoken about solidarity, ministry to the poor, a need to rethink our economic systems, and human fraternity.

Given the focus on these themes through Francis’s time as Pope, many assumed the document would encompass some of those themes. The encyclical is a compendium of past homilies, speeches, and statements Pope Francis has delivered in addition to new thoughts. The eleven core thematic areas of the encyclical are: (1) Immigration, (2) universal fraternity, (3) capital punishment, (4) international politics, (5) economic systems, (6) war, (7) interreligious dialogue, (8) private property, (9) racism, (10) peacebuilding, and (11) the lesson of the Good Samaritan.

The timing of Fratelli Tutti could not have been more prescient as the world faces the ongoing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic which exacerbates economic divides and poverty. The “virus” of racism, as Pope Francis calls it, is unfortunately present the world over and our international political system seems to be falling to the way of fascism in many places. This encyclical presents an alternative to the world we live in now. It imagines a world of universal fraternity that rejects neoliberal economics, just war theory, and the death penalty and works instead through an ethos of solidarity to uplift the rights of the most marginalized, specifically the poor and immigrants.

First generation liberation theologian Leonardo Boff, a friend of Pope Francis, states the new paradigm presented in Fratelli Tutti shifts the focal point of power from a “technical-industrial and individualistic civilization” to one of solidarity.[24] Fratelli Tutti draws heavily on liberation theology and offers a “skilled reading of the signs of our times” by examining the relationships between political and economic structures.[25]

Though it is rather clear Fratelli Tutti draws heavily on liberation theology, it is not clear that it can be considered a truly decolonial document. As theologian Felipe Gustavo Koch Buttelli states, a decolonial thought or method must encourage new subjects to become “agents on the reflective process”; specifically members of the LGBTQIA+ community, Black people, women, indigenous people, and members of other minority groups.[26] Though Pope Francis’s encyclical is rooted in liberation theology, it is not rooted in feminist liberation theology and thus misses out on critical components required to be considered a fully decolonial method.

One excerpt which seems to draw heavily on core themes of liberation theology comes from the section entitled “The joy of acknowledging others” and states:

Intolerance and lack of respect for indigenous popular cultures is a form of violence grounded in a cold and judgmental way of viewing them. No authentic, profound and enduring change is possible unless it starts from the different cultures, particularly those of the poor. A cultural covenant eschews a monolithic understanding of the identity of a particular place; it entails respect for diversity by offering opportunities for advancement and social integration to all.[27]

This excerpt explicitly calls for a need to ground societal change in the needs of the poor and of indigenous peoples. Pope Francis condemns the cultural and structural violence committed against indigenous people when colonizers erasure their histories and traditions. This excerpt perfectly captures another core theme of liberation theology, that liberation will not be possible without solidarity with the poor and the marginalized.[28] Koch Buttelli notes that one of the key aspects of decolonial theological thinking is that it must overcome a logocentric and rationalistic approach to knowledge; it must make space for centralizing Indigenous voices. This excerpt explicitly does that and is part of a larger theme in the encyclical which advocates for a turn to the local and a necessity to center the voices and work of indigenous peoples. This call to focus on Indigenous cultures is reminiscent of some of the themes of Laudato Si and the lived Indigenous experiences presented at the Amazon Synod in October of 2019. Pope Francis published Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home in 2015 and in it he wrote of the critical importance of combatting climate change and recognizing we cannot all flourish unless our environment is also flourishing because it too is God’s creation.

In reviewing Laudato Si, however, Professor Atalia Omer notes that though it has a strong critique of neoliberalism and exploitative capitalism, it strikingly leaves out a feminist perspective and does not go far enough to be decolonial. She says,

It [Laudato Si] exposes, by its omission, the requirement to connect the turn to indigenous epistemologies with feminist critical emancipatory theory, and also exemplifies that the practice of decolonizing religious traditions is necessary for decolonizing peacebuilding… Hence, elicitive approaches, without decolonizing and internally pluralizing and queering traditions themselves through double critique, remain instruments of violence and control, even if on the surface they lend authority to localized problem solving.[29]

This same critique can be offered to Fratelli Tutti because there is no explicit mention of feminist critical emancipatory theory. As previously mentioned, there is no commitment to an anti-patriarchal shift within the Church nor is there any reference to the varied and nuanced experiences of women in poverty as compared to experiences of impoverished men. Fratelli Tutti does not make any space to critique itself or dive further into feminist theological work which does not allow it to be considered truly decolonial. Though this excerpt from Fratelli Tutti has more decolonial aspects than the first, it still cannot be considered a decolonial method because it is not rooted in feminist liberation theology and critical emancipatory theory.

Another excerpt to consider from Fratelli Tutti comes under the heading, “The benefits and limits of liberal approaches”:

Neoliberalism simply reproduces itself by resorting to the magic theories of “spillover” or “trickle” – without using the name – as the only solution to societal problems. There is little appreciation of the fact that the alleged “spillover” does not resolve the inequality that gives rise to new forms of violence threatening the fabric of society. It is imperative to have a proactive economic policy directed at ‘promoting an economy that favours productive diversity and business creativity’ and makes it possible for jobs to be created and not cut.[30]

Reading this excerpt immediately calls to mind Fr. Gutiérrez’s critique of global capitalism and economic dependency. He boldly calls out systems of neoliberal economics which only further the imbalance between developed and developing countries but continuing to leave poor, developing countries behind.[31] This line is not a one-off line but rather a strong theme present throughout the encyclical that takes aim at capitalist societies that promote throw-away culture, and disregard the common good. Koch Buttelli asserts that another key fundamental aspect of decolonial theological work is that it must be anti-capitalist. He acknowledges that capitalism is more than just an economic system but rather an insidious and violent location of power that continually exploits the marginalized in the name of “progress”.[32] In Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis continually emphasizes the market economy can never fix deep rooted structures of colonialism and violence and points to the current pandemic as an example of how market freedom often exacerbates inequality instead of resolving it.

Though Pope Francis offers this sharp critique of capitalism, it cannot be considered truly decolonial because it is not intersectional. The encyclical fails to challenge the hierarchies of the patriarchal Church upon which it is resting. Koch Buttelli argues that the colonial matrix is “intertwined with capitalism in such a way that capitalism is racist, homo and transphobic, Western-centric, white, male and patriarchal…” and that a decolonial systematic theology most not only acknowledge the evils of capitalism, but it must explicitly make note of how it reinforces these other violent structures.[33] This excerpt also would not pass as a feminist decolonial theological text because it does not situate itself consciously in the world of poor and oppressed women, as Pilar Aquino expressed was imperative.[34] By omitting any mention of the disproportionate impact colonial and neoliberal systems have on women, girls, and those other than men, Fratelli Tutti leaves out feminist and queer perspectives and thus cannot be considered a fully decolonial method. This new encyclical creates an important opening for decolonial theory, but much like that of the first generation liberation theology, it lacks a feminist, queer, and indigenous perspective and thus cannot be considered to be a fully decolonial text.

IV.

The counterargument against this thesis pushes back against the very question raised in the first place: does the violence of the Catholic Church preclude it from actually being allowed to talk about decoloniality? As Maldonado-Torres argues, Christianity was violently imposed on Indigenous peoples through sexual abuse, domination, and enslavement.[35] The Church is complicit in this violence and does little to challenge it, benefiting from the social construction of religion as something that garners and holds power. The coloniality of knowledge asserted Christianity as one of the bedrocks of the true form of knowledge, thus giving it the power to shape discourses and ways of being for centuries to come.[36] For many, the original positionality of Christianity as a dominant force that imposed violence on indigenous people is too dark of a legacy to allow Christian thought to now try to engage in decolonial methodologies. However, the work of liberation theology is vastly different than any Christian theological work that has come before and is genuinely and deeply committed to atoning for the past sins of the Church through its exegesis of a preferential option for the poor. Fr. Gutiérrez directly states that the history of Christianity has been written by a “white, western, bourgeois hand” which compels the Church to center the experiences of Indigenous people that the Church has historically attacked.[37] Koch Buttelli argues that the Church can never fully apologize for its past mistakes if it does not dig deeper into them and engage with decolonial methodologies. He states, “A decolonial theology operates on the deconstruction of the theological legitimation of the colonial matrix of power and, in an intercultural approach, suggests heuristically new ways to understand God and God’s Kingdom, learning from different cultural system.”[38]

Taking into account this counterargument and the stronger arguments against it which assert the absolute necessity for the Church to engage in decolonial work, it becomes clearer how critical decolonial theory is to the existence of the Catholic Church. First generation liberation theology has offered the necessary start to the conversation of decoloniality within the Church. To continue the decolonial turn in the Catholic Church will require bringing the critical work of feminist liberation theologians to the fore and centering the lived experiences of poor and marginalized women in future work of the Church.

Pope Francis has the unique and important opportunity to listen to the cries of his Church. Though Fratelli Tutti is a step in the right direction, it cannot fully be considered a decolonial text in its current form because of its clear omission of feminist liberation theology, Black liberation theology, and queer liberation theology. The “People’s Pope”[39] can change the direction of the Church for the better but it will require him and the entire Roman Curia to acknowledge their complicity in a deeply patriarchal, heteronormative system which has systematically silenced the voices and work of feminist theologians throughout its entire existence. If Church leaders can learn to be brave enough to step aside and listen to the work of women in the Church then we will finally have a Catholic Church that is attuned to the needs of its people and committed to deep decolonial work which will in turn have ripple effects the world over.

Elizabeth Boyle is a Master of Global Affairs student at the University of Notre Dame with a concentration in International Peace Studies.

[1] Margerie, Bertrand de (1987) “Mary in Latin American Liberation Theologies,” Marian Studies: Vol. 38, Article 11., 57.

[2] Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez even goes so far as to say, “In Latin America we are in the midst of a full-blown process of revolutionary fermnet.” (from Gutiérrez, Gustavo “A Theology of Liberation”, 55.)

[3] Gutierrez, Gustavo, “A Theology of Liberation: History Salvation and Politics” Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1973, 15.

[4] Fanon theorized that the colonized must undergo a re-learning of their history, understanding the structural and systematic ways in which they have been colonized in order to achieve liberation and decolonization. Similarly, Fr. Gutiérrez argues that only the previously colonized members of Latin American society can achieve liberation because true liberation is rooted in overturning the oppression that they have been forced to embody.

[5] Gutiérrez, 171.

[6] Ibid. 56.

[7] Arce-Valentín R. “Towards a decolonial approach in Latin American theology.” Theology Today. 2017, 45.

[8] Ibid., 48.

[9] Andrade, Luis Martinez , “Liberation Theology: A Critique of Modernity”, Interventions, 19:5, 2017, 625.

[10] Ibid., 626.

[11] María Lugones, “Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System,” Hypatia 22:1, 2007.

[12] Pilar Aquino, María, “Latin American Feminist Theology”, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 14:1, 1998, 90.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 91.

[15] Ibid., 93.

[16] Ibid., 98.

[17] Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth, The Power of Naming , 108.

[18] Ibid., 105.

[19] Rivera, Mayra, “Thinking Bodies:The Spirit of a Latina Incarnational Imagination”, Decolonizing Epistemologies: Latina/o Theology and Philosophy, New York: Fordham University Press, 2011, 5.

[20] Ibid., 6.

[21] Ibid., 169.

[22] Ibid., 175.

[23] Rivera Rivera, Mayra, “Glory: The first passion of theology?”, 180.

[24] “Liberation theologian Boff, on ‘landmark’ Fratelli Tutti: ‘The Pope has done his part. It is up to us not to let the dream stay just a dream’”, Novena, Oct. 7, 2020, accessed at https://novenanews.com/boff-fratelli-tutti-pope-done-his-part-up-to-us/.

[25] Vicini, Andrea, “Fratelli Tutti: For a Better Kind of Politics”, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, Oct. 26, 2020, accessed at https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/fratelli-tutti-for-a-better-kind-of-politics.

[26] Koch Buttelli, Felipe Gustavo & Clint Le Bruyns, “Liberation Theology and Decolonization? Contemporary Perspectives for Systematic Theology”, 213.

[27] Fratelli Tutti, 2020.

[28] Gutierrez, Gustavo, “A Theology of Liberation: History Salvation and Politics”, 173.

[29] Omer, Atalia, “Decolonizing religion and the practice of peace: Two case studies from the postcolonial world”, forthcoming, 2020, 10.

[30] Fratelli Tutti, 2020.

[31] Gutierrez, Gustavo, “A Theology of Liberation: History Salvation and Politics”, 53.

[32] Koch Buttelli, Felipe Gustavo & Clint Le Bruyns, “Liberation Theology and Decolonization? Contemporary Perspectives for Systematic Theology”, 216.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Pilar Aquino, “Latin American Feminist Theology”, 105.

[35] Koch Buttelli, Felipe Gustavo & Clint Le Bruyns, “Liberation Theology and Decolonization? Contemporary Perspectives for Systematic Theology”, 208.

[36] Ibid., 209.

[37] Gutierrez, Gustavo, “A Theology of Liberation: History Salvation and Politics” 216.

[38] Koch Buttelli, Felipe Gustavo & Clint Le Bruyns, “Liberation Theology and Decolonization? Contemporary Perspectives for Systematic Theology”, 212.

[39] Chua-Eoan, Howard, & Elizabeth Dias, “Pope Francis, The People’s Pope”, Time Magazine, Dec. 11, 2013, accessed at https://poy.time.com/2013/12/11/person-of-the-year-pope-francis-the-peoples-pope/.