Liam Maher

The Life of Columbus murals, colloquially referred to as the “Columbus Murals”, at the University of Notre Dame have long stood for the school’s troubling inability to confront its perpetuations of white supremacy. Many in the University’s upper ranks have held their noses and begrudgingly defended keeping the murals on public display in spite of the murals’ dubious religiosity and blatantly racist caricatures of Indigenous and Black people. Activists and students who have for decades called for the murals’ removal have been met with incrementally minimal action. While recent advancements in this saga appear to be more substantial upon first glance, they have proven equally hollow in effect.

This inquiry examines the history of the University’s response to the Columbus Murals and critiques its most recent actions in response to a 2019 announcement that the murals would be concealed from the public. I demonstrate how the recommendations offered to the University’s president as well as the execution of said recommendations are inherently flawed as they replicate the very conditions activists and students have over the years sought to expel from the University. I subsequently counter the University’s current actions with a proposal that centers Indigenous voices as a direct response to Indigenous subalterning that has for over a century been condoned by the University through the continued display of the Columbus Murals.

Luigi Gregori’s Life of Columbus series was commissioned in 1880 by then-president of the University Edward Sorin, CSC. The work is an attempt to demonstrate the “Americanness” of Catholicism at a time when Catholics were seen as unwelcome imposters in the United States. To do this, Gregori portrays the glories of Columbus’ colonization as a mission of global unification under the banner of Christ. This sympathetic depiction of colonization as a moral triumph contradicts the well-documented centuries of cultural and physical genocide, abuse, torture, rape, slavery, and overall exploitation of Indigenous and Black populations on whose backs the Europeans built their empires. This ahistorical version of events is intentionally crafted to promote a white supremacist vision of America, something that has not gone unnoticed by the larger Notre Dame community.

For years activists and students led by the Native American Student Association (NASAND) at the University of Notre Dame have called on administrators to remove the Columbus Murals. Protests of the murals can be traced back as far as 1995.[1] In response to these first protests, the University administration added a stand with contextualizing brochures. The predominant contribution to the discussion from these pamphlets was a rich and detailed analysis of how many of the white figures in these murals are based on actual people while the Indigenous and Black figures in these murals have no real-life counterparts.[2] Lacking any critical analysis, these handheld brochures did little to counter the domineering murals that soar over visitors’ heads.

In 2017, over twenty years later, a letter opposing the murals with more than three hundred signatories was published by The Observer.[3] The administrative response to this more recent outcry took several years and came in the form of a 2019 letter to the campus community from the Office of the President. In this letter, President John Jenkins, CSC announces the University will no longer display the murals “regularly in their current location”.[4] The news was swiftly met with small but fierce backlash, particularly from conservative communities.[5] Shortly after the initial letter and ensuing responses, the Office of the President announced the formation of an ad-hoc committee to advise the mural covering process. The committee included only one Indigenous representative but several Italian and Catholic historians, as well as the Grand Knight for the Notre Dame Council of the Knights of Columbus, a fraternal organization dedicated to recuperating Columbus’ image as someone who “gave voice and representation to generations of Catholics, and helped pave a path for the diverse society we have today” in spite of the genocide in which he partook.[6]

The committee released an official report on July 25, 2019. The report prefaces the committee’s recommendations with a peculiar distinction between the “positive effects” of “evangelization of the Americas, and negative consequences, including disease, genocide, and the introduction of slavery, that issued from that event”.[7] The committee proceeds to make three recommendations. First, that the University begin developing an exhibition about the founding of Notre Dame, which would incorporate but expand beyond the Columbus Murals and their historical context. Second, the University should cover the murals only in a semi-permanent way to “allow faculty who utilize the murals in their work as scholars and teachers to continue to access them”.[8] The committee is vague on who should be involved in the design of these coverings, indicating that it is “ideal” to have “someone from the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi” involved on some level.[9] Third, the committee recommends that the University put more effort into celebrating Founder’s Day, a commemoration of founder Edward Sorin, CSC promoted by the University of Notre Dame. The committee lists panel discussions, symposia and a Powwow as suggested events to be incorporated into Founder’s Day festivities to provide space for conversations around race, identity, and Indigenous history.

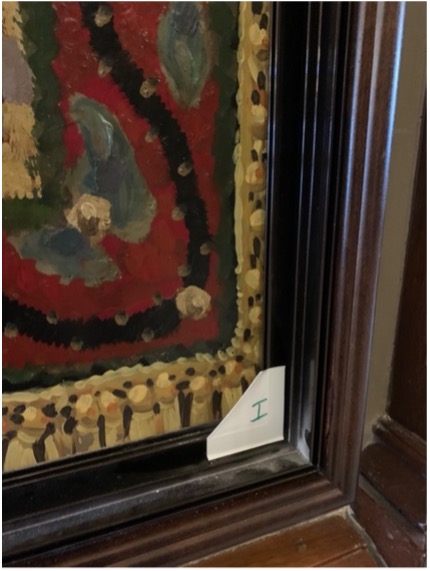

The University’s response to these recommendations has been partial at best. Two-years after President Jenkins’ first announcement, no exhibition about the University’s founding seems to be in progress. With the COVID-19 pandemic halting many in-person events, Founder’s Day panels and symposia are out of the question. The one item from the recommendations that has been fully implemented is the covering of the murals (Fig. 1). The mural covers are an attempt at “fusing the European aesthetic with the [singular] aesthetic of indigenous peoples”, per the Columbus Murals Committee recommendation.[10] Designed by Erik Baden of Conrad Schmitt Studios—a predominantly white design firm specializing in European neoclassical design—the coverings consist of screen-printed canvases mounted on sturdy metal frames which clip into place when installed.[11] The wall-mounted frames are screwed directly over the murals, but in order to fit have in parts been screwed directly through the edges of Gregori’s work (Fig. 2). Trees, flora, fauna, stars, and leaf-like borders “reflect natural and geometric motifs of the Pokagon Band of the Potawatomi” according to a report in Notre Dame Magazine.[12] It is uncertain if these motifs are distinct to the Pokégnek Bodéwadmik, as some (like the turtle depicted in Fig. 1) are references to cross-cultural Indigenous creation narratives. Other motifs run afoul of exoticism, perpetuating romanticized notions of Indigenous aesthetics: another colonial logic. There was no publicized announcement when the murals were uncovered in the spring of 2021, nor was NASAND consulted. The murals also remain uncovered for days at a time, as several students have been keen to note on social media.

The recommendations of the Columbus Murals Committee and the University’s implemented changes embody what bell hooks identifies as a shortcoming in postmodern colonial dialogues. She writes, “it is only white people who are angels, only white men who dialogue with one another, only white men who interpret and revise old scripts”.[13] Rather than make space for non-white voices and cede power to the disenfranchised in conversations on repairing the harm of colonization, white people try to retain control of the dialogue. This has been the case with the response to the Columbus Murals beginning with the formation of the Columbus Murals Committee.

In its very structure, the committee was inclined to defer to white perspectives on the murals. With only one Indigenous representative on the official committee, no new space was created to foster a dialogue that could actually respond to the needs of the community. Instead, the same white power structures that led to the committee’s formation were replicated under the guise of progress. Groups like the Knights of Columbus who represent a minority of American Catholics were arguably given a larger platform through their equal representation on this committee, which served only to benefit white oppressors.[14] Rather than address the historic oppression of Indigenous voices by uplifting, centering, and prioritizing the voices of the harmed, the Columbus Murals Committee instead reproduced the same harmful power dynamics that silence Indigenous voices.

Through its sympathetic defense of both evangelization and Columbus, the committee’s official report exemplifies white culture that “looks at itself somewhat critically, revising here and there, then falling in love with itself all over again”.[15] In making the assumption that the evangelization of the Americas was a positive end distinct from the horrors of genocide, cultural erasure, and violence wrought by colonization, the committee sidesteps the harsh reality that evangelization is colonization. Such a perspective fails to consider the political dimensions of Christianity and the use of Christian religion as justification for violence against non-white peoples, a demonstrated habit of European Christians throughout history.

Once this false distinction between evangelization and colonization was made, the resolution to remove the murals quickly softened to an equivocation between hiding racist roots and parading them in the name of education. The gentle slide from committing to removing these murals to selectively concealing them is “intertwined with white supremacy”, for “this evil slipperiness is enacted with as much racist intent as what spawned the creation of these monuments in the first place”.[16] In conceding to uphold white supremacist norms rather than innovate ways of dismantling them, regardless of how much they speak against them, the Columbus Murals Committee as well as the University defaults to the same racist agendas that motivated the creation of these murals. The newly-installed coverings epitomize this regression. In selecting a predominantly white design studio with no experience in Indigenous arts or culture, the University missed an opportunity to pay Indigenous artists to respond to these murals in a meaningful way. The attempt at a fusion of European and Pokagon aesthetics from the perspective of the colonizing class is a tactless decision to speak on behalf of Indigenous people, again missing an opportunity to embrace art and lessons from Pokégnek Bodéwadmik creatives.

Whiteness is again centered in the proposed Founder’s Day celebrations. Rather than embrace the increasingly popular Indigenous Peoples’ Day or another holiday focused on non-white figures, the Columbus Murals Committee proposes increased emphasis on celebrating a white colonizer through ambiguously organized panel discussions, symposia, and talks without any planned material consequences. The Indigenous presence in this model is reduced to a Powwow which, while certainly meaningful, borders dangerously close on the commodification and fetishization of Indigenous culture and rituals.

As artist/activist Jillian McManemin writes, “efforts to preserve these monuments [to colonialism] and prevent their toppling signal a desire to allow them to continue to exert their power […] to uphold the ideas they stand for, and, perhaps most significantly, to communicate that property is more important than people”.[17] As long as the Columbus Murals remain visible in any capacity, as long as Founder’s Day remains a focusing point of the University’s history, and as long as white voices are the ones dictating how the University responds to Black and Indigenous oppression, the University of Notre Dame chooses to preserve and promote the racist propaganda of the Columbus Murals in which Christianity guides the non-white world to its death.

Replacing the Gregori murals requires a nuanced and tailored approach. Any public-facing artwork “requires the people envisioning what a monument should be” in their own space.[18] Art that occupies public space should be the vision of the public whose space it occupies, not the vision of an authority detached from the people. Realizing this requires the “insights of a diverse audience”.[19] Such collaborative efforts will push communities to “confront their own racism”, but this is an essential step towards a better future, especially when responding to racist art.[20] Gregori’s murals do not need to be preserved in their original form for educational purposes. More of Gregori’s work can be seen in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart mere steps away from Main Building, and no aspect of the Columbus Murals is too elusive for contemporary digitization/documentation tools to capture. So long as adequate digital files are created and a thorough archive of related materials is maintained, there need not be fear of “forgetting the past” or “erasing” history. We must fear, however, the preservation of white supremacist and colonial structures in symbolic and literal forms.

The proper response to these murals would be their toppling through transformation. The only way to counter racist actions is with anti-racist action. In that spirit, full authority over the Columbus Murals should be given to Indigenous people. As descendants of the University’s first students, the Pokégnek Bodéwadmik in tandem with NASAND should be allowed to commission new works that respond to Notre Dame’s colonial history and celebrates local Indigenous history. These works might symbolically deface the murals, appropriate them, or wholly replace them. The details of this should be determined by to those given autonomy over this space. Not only would this free the University administration from having to make decisions they are ill-equipped to handle, it would also empower and motivate students and community members around a common project, creating a rich partnership sure to bear great fruit. This gesture would also blend symbolic and material reparations by returning to Indigenous people physical space that was once used to oppress them. This would be a necessary and powerful first step in more comprehensive reparations and land rematriation.[21]

For a university like Notre Dame so concerned with its public image, this is perhaps a daunting prospect. Such vulnerability, though, is not unprecedented. Other colleges have responded to similar situations through radical means. One such example comes from the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA). The JSMA is known for its iconic and somewhat reductive façade, an eclectic mix of traditional “Western” and “Eastern” architectural styles representing the museum’s robust Asian and Latin American/American collections (Fig. 3). On the façade, two small niches flank a central entrance. Above each are quotes from Plato, the Book of Proverbs, and Lao Tzu, again representing a harmonious blend of Eastern and Western philosophies. Noticeably absent from this design are any Indigenous American influences.

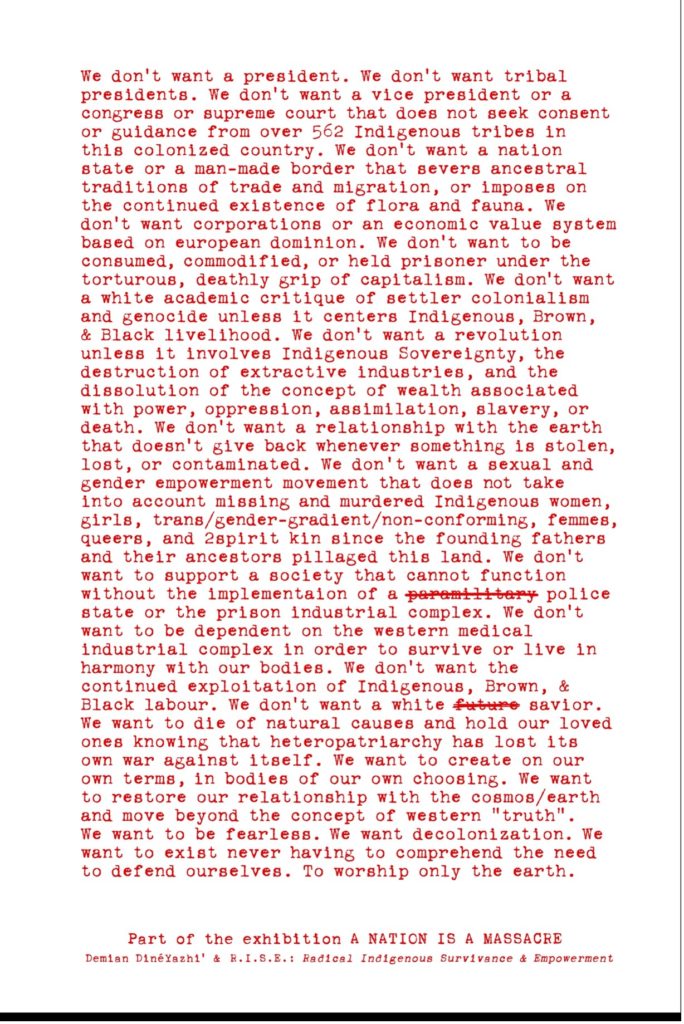

A 2020 installation by Demian DinéYazhi’ (Nádleehí Diné) responds to this blatant absence. DinéYazhi’, who was awarded a Hallie Ford Fellowship by the JSMA, used their grant to install a quote in one of the façade niches (Fig. 4). The lengthy quote is DinéYazhi’’s poem “We Don’t Want A President”, first written in 2018 for the exhibition A NATION IS A MASSACRE. Their poem is a playful yet strong rebuke of Zoe Leonard’s “I Want A President” poem from 1992, going further than Leonard by rejecting even the notion of presidency, of nation, and of Western ways of being, calling for a return to the earth and a return to Indigenous sovereignty, which includes liberation for Black and brown people.

This poem is now displayed on a prominent campus quadrant at the University of Oregon in the installation We Don’t Want A President… A sleek glass panel bearing the text of the poem looks out at passing students who rush back and forth from the nearby library to classroom buildings across the quad. The panel fills one niche on the JSMA’s façade, leaving the other open in anticipation of another silenced voice waiting to be given a platform. Though the installation is temporary, the potential it embodies makes space for future artists to respond to institutional silencing.

By ceding space to an Indigenous artist, the JSMA was able to foreground through art the Indigenous erasure ingrained in the museum’s design. The institution’s vulnerability allowed an important and powerful conversation to take place. When responding to issues of Indigenous autonomy and sovereignty, institutions of higher learning owe it to their students to engage in dialogue with honest self-awareness and an openness to being educated. The Columbus Murals and the decades-long saga to remove them from the University of Notre Dame provide an example of the pain, complications, and regression that result from an unwillingness to embrace such vulnerability. This struggle may seem trivial, but the enshrinement of racist public art on college campuses perpetuates environments of white supremacy that exclude many from reaping the full benefits of their education. Rather than sidestep difficult conversations by refusing to cede metaphoric and physical space to those harmed, institutions must swallow the bitter pill of following instead of leading with the goal of learning from outside the echo chambers of the institution.

Liam Maher is an alumnus of the University of Notre Dame. He is a doctoral student in art history at Temple University and founder of Accomplice.

[1] https://www.indystar.com/story/news/local/2017/12/03/notre-dame-students-want-these-christopher-columbus-murals-removed-saying-they-fo-celebrating-slaver/917687001/.

[2] This brochure even notes the Taino people depicted in the murals are inaccurately represented in the clothing of the Plains Indians, a choice Gregori made out of convenience.

[3] https://ndsmcobserver.com/2017/11/time-murals-go/.

[4] https://president.nd.edu/presidents-initiatives/columbus-murals/.

[5] https://www.yaf.org/news/notre-dame-yaf-condemns-cowardly-decision-to-cover-columbus-murals/; https://ndsmcobserver.com/2019/02/covering-columbus-murals-disregards-notre-dames-italian-americans/.

[6] http://www.kofc.org/en/news-room/articles/honoring-columbus-and-his-legacy.html.

[7] Recommendations of the Columbus Murals Committee, July 25, 2019. Report. https://president.nd.edu/assets/334683/columbus_murals_committee_report.pdf, 1.

[8] Recommendations of the Columbus Murals Committee, 3.

[9] Ibid., 3.

[10] Recommendations of the Columbus Murals Committee, 3.

[11] https://magazine.nd.edu/stories/columbus-murals-covered/.

[12] Ibid.

[13] bell hooks, “Representing Whiteness: Seeing Wings of Desire” in The Visual Culture Studies Reader, ed. Nicholas Mirzoeff (Routledge: London, England, 1998), 342.

[14] As of 2019, the National Catholic Reporter counted approximately 1.9 million members of the Knights of Columbus worldwide. According to a PEW Research Center study one year prior, there are 51 million Catholics in the United States alone.

[15] bell hooks, 338.

[16] McManemin, Jillian. “Let’s Preserve Acts of History, Not Racist Monuments” in Hyperallergic. September 21, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/589365/toppled-monuments-archive-op-ed/.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Judith Baca quoted in Doss, Erika. “Raising Community Consciousness with Public Art: The Guadalupe Mural Project in Spirit Poles and Flying Pigs: Public Art and Cultural Democracy in American Communities (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 158.

[19] Doss, 159.

[20] Ibid., 179–180.

[21] The use of “rematriation” instead of “repatriation” is intentional here, for in certain Indigenous cultures (including the Pokégnek Bodéwadmik) communities are led by women, not men, and thus land is discussed in terms of ownership by women. This can be seen in the January 20, 2020 Reparations & Reconciliation at Notre Dame panel co-sponsored by the Mediation Program and linked in Accomplice.