The Cost of Illness

Illness comes with overwhelming amounts of pain, symptoms, trauma, and costs. These emotions consist of negative feelings such as guilt, frustration, apathy, hopelessness, anxiety, loneliness, denial, grief, and disempowerment. Healthcare and treatment costs are at an all time high, leaving behind concerning levels of debt and a lack of affordability for those who need help most. Symptoms and effects of illnesses are not always properly understood; therefore, it is not always known how to treat them. The list of the struggles for the sick person goes on and on. All of these factors shape individuals’ experiences and therefore shape their livelihoods. However, there are other factors that end up placing an additional burden on the sick. Each sick individual’s immediate communities as well as their social environments work hand in hand to affect their personal interpretation of their illnesses through defining them with stigmas, utilizing the ideology of health, and pushing for the creation of controlling health practices.

First, I will elaborate on how our healthcare system and the society we live in create and place powerful stigmas on the sick, utilize the ideology of health to form systems of beliefs, and misuse their power to control society. Then, I will detail the numerous mental and emotional effects these factors leave on the sick. I will conclude by discussing possible solutions to these issues, specifically focusing on how physicians can better their care of those who are ill.

The Social Meaning of Sickness

Every sick individual has their own unique personal human experience of their symptoms and their suffering. However, both their immediate community as well as their social one adds an additional burden and an additional dimension of suffering they are forced to deal with through stigmas, ideologies, and methods of control.

“Acting like a sponge, illness soaks up personal and social significance from the world of the sick person.”

Kleinman Arthur, Illness Narratives, 2017.

The Power of Stigmas

Stigma is defined by Goffman as discredited attributes that are clearly visible and identifiable, marking patients with disgrace and shame, spoiling their identity, and creating an internalized feeling of being inferior and less than (Goffman 2022). They become defined as straying away from the “normal” status quo as their health is altered in some way, leading to them becoming “disqualified from full social acceptance” (Goffman 2022). My younger cousin is incredibly intelligent, most likely the smartest person I know at the young age of 14. He excels in school, rapidly spits out definitions of complex vocabulary terms, easily explains difficult concepts, and is incredibly quirky with his random comments and daily quotes. His personality and knowledge astounds me everyday. However, he is looked at differently because of his disability. He was diagnosed with autism at a very early age. This has led to him getting degraded and picked on by peers, labeled and placed in a box by educational professionals, and defined by healthcare workers. They all base their understanding of who he is on his differences. “The stigmatized person is defined as an alien other…whose persona…the group regards as opposite to ones it values. In this sense the stigma helps to define the social identity of the group” (Goffman 2022). My cousin is a prime example of an individual who is labeled as “other” by people in society and people in positions of power.

Ideologies and Their Effects

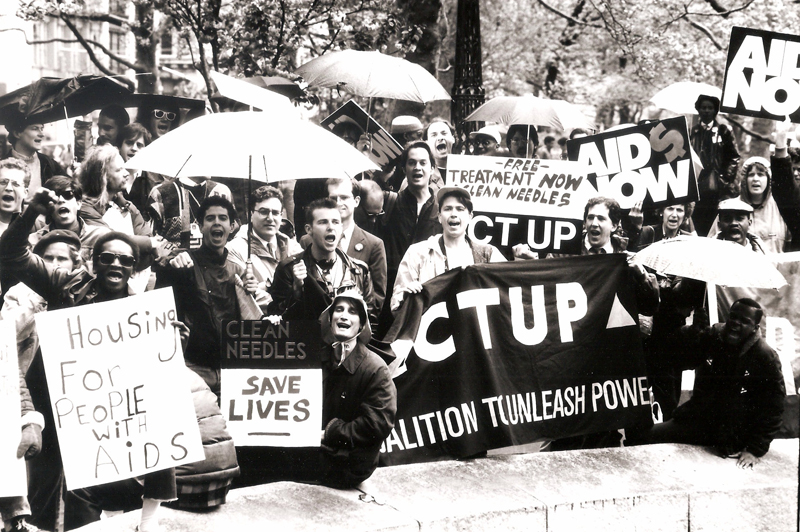

Ideology is philosophical. It is symbolic and it is practical. It is a system of beliefs shared by a certain group in an effort to shape action, succeeding by covering up patterns of dominance, power, and inequality (Crawford 2006). Ideology becomes acceptable to us. Crawford argues that health itself is an ideology that is powerful and effective as a form of social control as it succeeds in pushing us to participate in certain behaviors and consume certain goods (Crawford 2006). It works to replace the concern for a mutual obligation with a sense of tackling sickness with an individual responsibility for health. In the film “How to Survive a Plague” on the AIDS epidemic, those suffering with AIDS were held to the personal responsibility of fighting for themselves, doing their own research, finding their own drugs and treatment, and using their own voices to protest and stand up against lawmakers and pharmaceutical companies (France 2012). It was clear that those in power were not prioritizing the issue, owning up to their responsibilities of protecting the health of citizens, or assisting those who were suffering incredibly.

Establishment of Control Using Health

In addition to stigmas placed on people and the ideology of health affecting quality of care, the sick person battles differing forms of social and moral control. Medicine and health have become a form of authority that is not often questioned. There is a control over technology and jurisdiction over what is considered to be a good life. There is this idea that there is a rational and objective way to maintain healthy lifestyles and deal with certain illnesses in a way that is deemed “right.” When there is any attempt to step away and do anything in a different way, they are looked down upon and defined as resisting the correct way to heal. This takes an additional step towards labeling people. We become defined as being sick, dysfunctional, or needing medical intervention, leading to healthism where there is no upper limit of health, wellness, and fitness. There is always more you can do to remain healthy or heal. Sick people are pressured to answer two main questions of “why me” and “what can be done.” Without the answer to these questions, they may feel that they have failed, not dealt with their illness in the “correct” way, and deserve to be ill or that it is in some way their fault.

All in all, health practices act as a way to control, hack, and exploit the sick without having to force or coerce them as the effectiveness of social control removes the need for central or government power. A prime example of this is the overwhelming presence of wellness programs from gyms in work offices to the promotion of cycling classes and pilates. These work to create a more productive workforce, reduce liability through providing resources for healthy lifestyles, and attract more employees with the appearance of benefits (Winant 2018). Winant highlights Ehrenreich’s observance of the “fixation on controlling the body encouraged by cynical and self-interested professionals in the name of wellness” and how self care has become “a coercive and exploitative obligation [with] endless medical tests, drugs, wellness practices, and exercise fads that threaten to become the point of life” (Winant 2018).

Moving Forward: Recommendations for Clinicians

So how do we move forward from here? What steps can we take to better treat and care for the sick in a way that respects their dignity and right to fair care and treatment? We must ask ourselves how we can provide the utmost compassion and most effective care and treatment. It starts with those in power and those who interact most closely with the sick. This means physicians must take the first step. In this way, we can work to tackle the many issues that exist and thrive in our societies, hospitals, schools, and even homes.

Kleiman has offered some incredible advice for how we can take steps to achieve this through affirmation, listening, and offering empathy and compassion. He stresses that clinicians should work to affirm both the patients and their family members’ experience with a certain illness as constituted by lay explanatory models (Kleinman 2017). He also highlights the need for empathetic witnessing, which is listening (with care and intention) to what he calls the sick person’s persona myth or the story that they tell in an attempt to make sense of their illness (Kleinman 2017. We must also listen to their and their families fears and the trials and tribulations they face while mirroring these stories back to the patients in order to assist these patients in constructing these narratives (Kleinman 2017. I love these pieces of advice because in my opinion, one of the most important aspects of caring for an individual and bettering their health is forming proper relationships with them, relationships with total and complete care, fair equal dynamics, and dignity for the sick. Compassion and the feeling of being heard and understood is so important as those that are sick often face the experience of not having their voices heard, being constantly invalidated for their pain and emotions, and having their personal experiences be overlooked.

References

- Crawford, Robert. “Health as a Meaningful Social Practice.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, vol. 10, no. 4, 2006, pp. 401–420., https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459306067310.

- France, David, director. 2012. How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects. 109 min.

- GOFFMAN, ERVING. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. PENGUIN BOOKS, 2022.

- Kleinman, Arthur. “The Illness Narratives.” Academic Medicine, vol. 92, no. 10, 2017, p. 1406., https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001864.

- Winant, Gabriel. “A Radical Critique of Wellness Culture.” The New Republic, 23 May 2018, https://newrepublic.com/article/148296/barbara-ehrenreich-radical-crtique-wellness-culture.