The Medicalization Debate

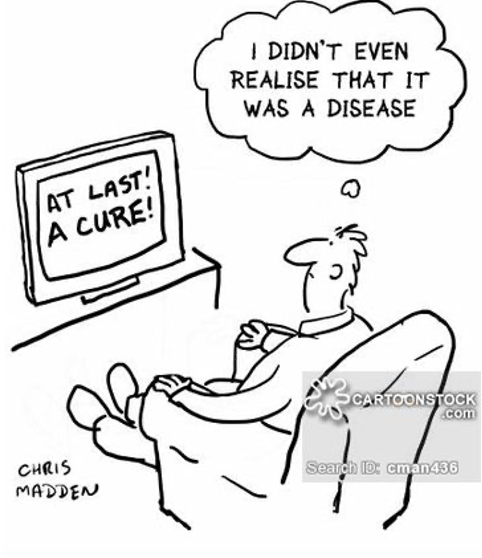

The healthcare field has been one of the fasted growing industries across the globe in recent decades as researchers and medical professionals continue to search for new and improved forms of care. Advancements in new technology, drugs, and our understanding of various health-related conditions are constantly being made and shaping our perception of the world we live in. As Robert Crawford points out in his publication Health as a Meaningful Social Practice, medical policies, forms of treatment, and the way in which we understand different medical conditions influences how we perceive ourselves within the social sphere of society (Crawford, 2006). This relationship between healthcare and social practices becomes especially important when discussing the concept of medicalization. Medicalization refers to the process in which non-medical problems become redefined within the scope of medicine and are treated as such, according to Peter Conrad from Brandeis University (Conrad, 1992). Medicalization has become a point of focus recently as improper identification of an issue as being medical-related could have harmful effects on both patients and society as a whole. Researcher Erik Parens points out that medicalization itself is not necessarily a bad thing, but rather it becomes an issue when the medicine oversteps its limitations (Parens, 2013).

Emilia Kaczmarek describes four major risks that may arise in the case of over-medicalization. First, over-medicalization may have a negative impact on patient health as it promotes excessive treatment that could lead to undesirable side effects. Next, over-medicalization has an effect on the economy as it can promote the misplacement of both public and private funds. Third, over-medicalization can have important psychological implications by stigmatizing certain individuals or their “condition” as being sick and restrict personal freedom through pressures to alter one’s behavior to the standards of society. Finally, over-medicalization overlooks the different social, political, and interpersonal relationships that may play a role in the problem a person is facing (Kaczmarek, 2018). Excessive medicalization can be seen in a number of different examples, such as ADHD, women and childbirth, menopause, erectile dysfunction, sleep disorders, and much more. In each of these cases, the condition is viewed through a biological lens that causes other contributing factors to be overlooked and an emphasis to be placed on medications and other medical treatments. This reading will be focusing on the influence medicalization has had on ADHD specifically and the impact this has had on the most vulnerable patient population: children.

A Snapshot of ADHD in the U.S.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention describes ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder that is commonly diagnosed during childhood and persists through adulthood (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022). The condition is typically associated with an inability to pay attention, difficulty controlling impulsive behaviors, and being excessively active. In the U.S., it is estimated that around 6 million children are currently diagnosed with ADHD with over 265,000 of these diagnoses occurring in children between the ages of three and five (CDC, 2022). Of this patient population, 62% were consistently taking ADHD medication while 47% were receiving behavioral treatment for a combined 77% of children with ADHD taking some form of treatment. Behavioral treatment for ADHD does not have an impact on the core symptoms experienced by these patients, but rather it involves teaching children various coping strategies in order to control their symptoms. Behavioral therapy is comprised of two main components in order to help children manage the various symptoms of ADHD. The first is what is known as “parent training” that focuses on teaching children how to control their impulsive behavior. This portion of therapy involves both the children and their parents and provides parents with different strategies in dealing with their child’s behavior. The second form of behavioral therapy deals with what is known as “executive functions.” These executive functions are a set of skills that enable a child with ADHD to better manage their time, stay organized, and plan different tasks (Miller, 2022).

Although, nearly half of all diagnosed children are involved in ADHD behavioral therapy, treatment in the form of medication is much more common and also more relevant to the topic of medicalization. ADHD medication primarily involves stimulants such as methylphenidate or amphetamine. These stimulants, which include well-known brand-name drugs like Adderall and Concerta, are the most commonly used ADHD medications and are often varied by dosage depending on the patient’s needs. In general, long-term use of stimulants can have adverse health effects, primarily on the cardiovascular system, as it can lead to chronic high blood pressure, increased heart rate, and heart failure (Losch, 2023). As a result, concern has grown regarding prescribing ADHD medication to children, especially since some may begin taking these drugs as young as three years old.

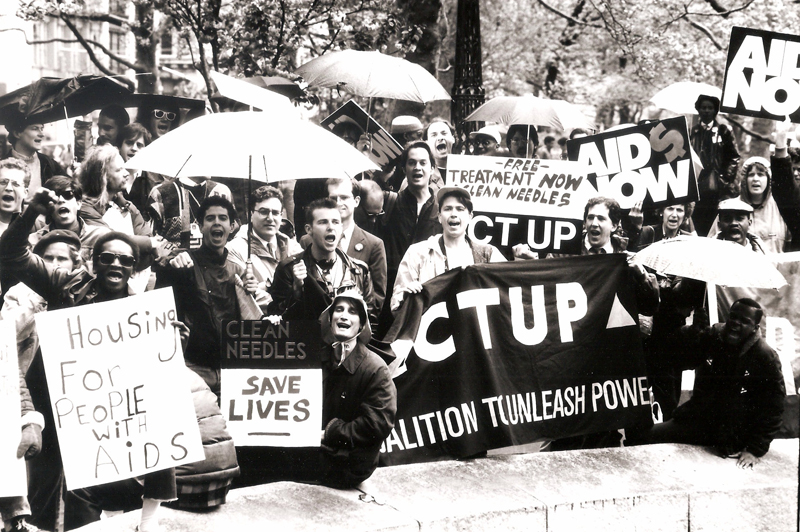

Only a small fraction of children with ADHD have outwardly hyperactive symptoms.

ADDitude Magazine

The Medicalization of ADHD and the Risks it Poses to Children

With nearly 1 in 11 children in the U.S. currently having an ADHD diagnosis and this rate of instance steadily increasing since 1997, it calls into question the reason for this growing prevalence (Lanham, 2023; CDC, 2022). Are more people in the U.S. being affected by ADHD, is improved testing allowing for more accurate detection of ADHD, or is our understanding and perceptions of ADHD changing and causing a greater number of people to fall under what society categorizes as ADHD? This is where the topic of medicalization becomes relevant. The over-medicalization of ADHD has the potential to increase the rate of diagnosis in children and, as a result, increase the number of children receiving medicated treatment. It is possible that more people are not actually suffering from ADHD, but rather societal pressures, expectations, and norms are shaping how we view the condition. The structure of the U.S. education system requires students to sit at their desk for prolonged periods of time and often does not involve a lot of physical movement. When a kid fails to adhere to expectations that they remain attentive and non-disruptive for these prolonged periods of time, the first assumption may be that they are suffering from ADHD since an inability to focus and control impulsive behavior is associated with this condition. In today’s world, there is a much greater public awareness of ADHD that has caused it to become de-stigmatized, which could explain the growing numbers of cases. The inability of children to focus in a classroom setting may have previously been thought to be related more to the energetic nature of children, but increased public awareness has created an over-emphasis on the correlation between ADHD and hyperactivity in children, leading to far more diagnoses.

The reason that the changing perception of ADHD in society, leading to more supposed cases, is important again comes down to the emphasis on using of ADHD medication to treat the disorder. The nature of stimulants, like ADHD medications, can create a number of different side effects in those taking them. ADHD medications have been known to cause sleep problems, decreased appetite, delayed growth, frequent headaches and stomachaches, irritability as the drug wears off, tics, and changes in mood (Boorady, 2022). This has caused great concern in prescribing children these medications as they are undergoing significant neurological, hormonal, and physical development and the long-term impact these effects can have on this development are mostly unknown as most studies often involve non-human subjects due to the many ethical concerns of experimenting on humans (Volkow, 2008). The fact that the experience and severity of ADHD often varies among individuals can lead to an increase in the number of patients being diagnosed with and receiving treatment for ADHD as well. According to a study published in the National Library of Medicine, there is not a single pathophysiological entity that causes ADHD, but rather multiple risk factors work together to promote the condition we know as ADHD (Curatolo, 2010). This creates the potential for a number of different neurological conditions and features to be classified as having ADHD implications when they may not necessarily cause ADHD themselves and, therefore, more children may qualify for an ADHD diagnosis. This prevents the development of a biologically based test for diagnosing children and instead diagnosis relies on the clinician’s perception of the child’s behavior and parent description.

Conclusion

The over-medicalization of various disorders and conditions has major implications on patient health and overall quality of life. Viewing these disorders with an emphasis on their biological and medical applications opposed to a more comprehensive understanding of the different factors that may contribute to them may negatively affect the patients living with these problems. This becomes more relevant for disorders that are typically diagnosed in children as there could be many long-term effects that have the potential to adversely affect the patient later in life. ADHD is one of these conditions that generates a great deal of concern, especially since the main form of treatment for ADHD in children is prescription drugs. The over-medicalization of ADHD has the potential to increase incidence of diagnoses, and result in a greater number of children taking these prescriptions. ADHD, like many other overly medicalized conditions, lacks a strong biological basis where biological markers can be used to make a diagnosis. Instead, clinicians rely on observed behavior of the patient and descriptions from parents to make the decision of whether or not the child should be treated with a strong chemical compound. Understanding the role that medicalization has on our perception of conditions like ADHD and how this can influence our decisions is key in being able to prevent excessive treatment in vulnerable patients that may not necessarily require treatment.

Works Cited

Behavioral treatments for kids with ADHD. Child Mind Institute. (2023, January 25). Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://childmind.org/article/behavioral-treatments-kids-adhd/

Carpiano, R. M. (2001). Passive medicalization: The case of Viagra and erectile dysfunction. Sociological Spectrum, 21(3), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/027321701300202082

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 9). ADHD throughout the years. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 9). Data and statistics about ADHD. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 9). What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html#:~:text=ADHD%20is%20one%20of%20the,)%2C%20or%20be%20overly%20active.

Conrad, P. (1992). Medicalization and Social Control. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 209–232. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001233

Crawford, R. (2006). Health as a meaningful social practice. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 10(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459306067310

Curatolo, P., D’Agati, E., & Moavero, R. (2010). The neurobiological basis of ADHD. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 36(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-36-79

General prevalence of ADHD. CHADD. (2022, October 20). Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://chadd.org/about-adhd/general-prevalence/#:~:text=5.1%20million%20children%20(8.8%25%20or,%E2%80%9317%20(1%20in%2010)

Is there an increase in ADHD? CHADD. (2019, July 11). Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://chadd.org/adhd-weekly/is-there-an-increase-in-adhd/#:~:text=Greater%20public%20and%20professional%20awareness,and%20getting%20treatment%20for%20children.

Kaczmarek, E. (2018). How to distinguish medicalization from over-medicalization? Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 22(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9850-1

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2023, January 25). Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/adult-adhd/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350883#:~:text=and%20certain%20medications-,Treatment,they%20don’t%20cure%20it.

PARENS, E. R. I. K. (2011). On good and bad forms of medicalization. Bioethics, 27(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01885.x

Side effects of ADHD medication. Child Mind Institute. (2023, January 25). Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://childmind.org/article/side-effects-of-adhd-medication/

Staff, P. R. C. (2022, June 7). The long-term consequences of stimulant use. Pinelands Recovery Center of Medford. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.pinelandsrecovery.com/the-long-term-consequences-of-stimulant-use/

Volkow, N. D., & Swanson, J. M. (2008). Does childhood treatment of ADHD with stimulant medication affect substance abuse in adulthood? American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(5), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020237