In a society where being healthy is a high standard that people strive to attain, it can be very detrimental to a person when they are diagnosed with an illness that has no cure. The society we live in today has always been very individualistic in the sense that people are expected to become healthy and return to doing what they have been doing before they became sick. There is an idea that people who become sick could have avoided it by changing their lifestyle and habits. In this society, having any illness would make one feel like a burden, feel guilty, or have a sense of uselessness. Sadly, we live in a society where people with these illnesses are not treated with respect. As someone with a great family friend that was diagnosed with HIV, it can be heartbreaking to see the many ways that this diagnosis interferes with their self-image and life. As someone who also has hopes of going to medical school and becoming a doctor, the way that shame and disease can impact people is something that I want to keep in mind to provide patients with the best care. I hope to talk about the background of HIV/AIDS, the negative experience of people with illnesses and diseases, the impact of stigma and shame, and disparities in this disease that causes people with it to be an easy target for discrimination along with ways that physicians can slightly improve the experience.

HIV/AIDS Background

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks cells that help with fighting infections in the human body (“What Are..”). HIV can be contracted by having contact with bodily fluids such as sharing injection drug equipment along with unprotected sex. Leaving HIV untreated leads to AIDS which is acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (“What Are..”). Although there is no final cure for HIV, people can take antiretroviral medications that are used to treat it, helping people live longer lives (“HIV and..”). Although there are many ways to contract HIV/AIDS, with the most common being drug equipment and unprotected sex, casually interacting with people does not put you at risk which is what makes the discrimination people with HIV/AIDS face very disconcerting

Source: HIVinfo.NIH.gov. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/basics-hiv-prevention

Experience of Illness: Stigma and Shame

My family friend with HIV/AIDS has mentioned to me many times that his friends would stop reaching out to him once they found out he had it and would describe how doctors would keep their distance from him. Illness can be defined by the human experience of having to live with the symptoms of pain and suffering. The definition of illness and disease is summed up well in Illness Narratives. Since illness is an experience one has to go through, people can become demoralized, lose hope, or feel as if they are a burden to the people that are taking care of them (Kleinman, 1988, Chapter 1). Disease refers to the problem from the physician’s perspective meaning the experience of one who lives with the illness is not taken into account. There is great danger in not considering the lived experience of a person with a disease and the many obstacles they encounter. HIV/AIDS is viewed as a major threat to the major values of American society. In today’s society, people with AIDS are blamed for their “promiscuous sexual practices” (Kleinman, 1988, Chapter 1). AIDS in a way brands the person with the idea that they deserved it for the way that they were acting (Kleinman, 1988, Chapter 1).

In the case of Horacio Grippa, he not only had to deal with the symptoms that HIV/AIDS had on his body but also the way that he was treated because of it. His illness defined him in a way that got him kicked out of his apartment and made him lose his job as a teacher. He also mentioned how his nurses seemed scared to come close to him and how the doctors he would encounter would wear masks and gloves (Kleinman, 1988, Chapter 10). As a person who wants to become a doctor someday and knows someone with HIV/AIDS, reading this was emotionally taxing. For a patient, seeing a doctor should be a relief and someone that they can count on. The fact that some patients are still discriminated against because of having HIV/AIDS is truly concerning. When I become a doctor, I would hope to treat everyone with respect and make them feel safe and welcome because they already come to see you in a very vulnerable position.

Disparities with HIV/AIDS that Lead to Easy Targets of Shame Along With Ways of Improving as a Medical Provider

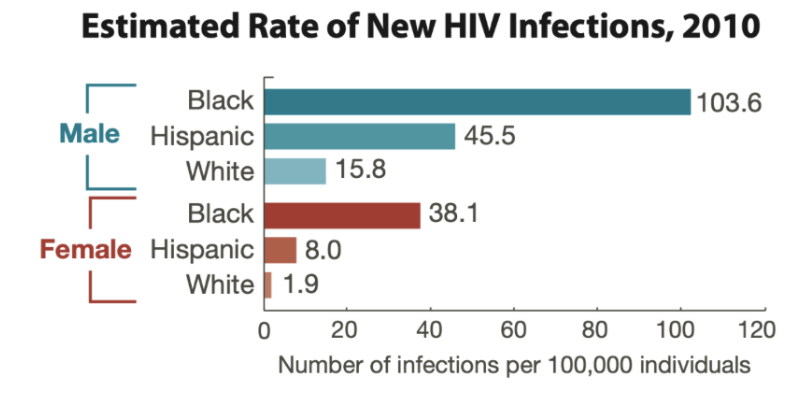

In the early stages of HIV/AIDS, the predominantly affected were homosexual and bisexual men since they made up 63% of AIDS-reported cases (Bosh et. al). In 1986, the CDC began to report the disproportionate effect that HIV/AIDS was having on African Americans and Latinos (“A Timeline”). The prevalence rate of HIV for African Americans is nearly eight times greater than for white people and three times higher than for Latinos (Geary). These statistics show that HIV/AIDS is common in minority communities that are already great targets for discrimination and shame. This can also make it easier to categorize a group of people and make them feel responsible for the high prevalence rates of HIV/AIDS.

There are many ways of improving the experience that patients encounter, especially when it relates to stigma and shame. As people that work in a clinic or are doctors, one can be understanding of the challenges that patients have such as obstacles that could cause them to need more time to make it to appointments in the example of using a wheelchair. Doctors must overcome certain biases that they are taught and always listen to their patients by not disregarding the symptoms that they are having. There must also be a reconceptualization of medical care where the physician shows empathy and takes the patient seriously. Although this will not solve all the problems and biases experienced by the patient, it would be the first major step in making them feel heard and important (Kleinman, 1988, Chapter 2).

References

“A Timeline of HIV and AIDS.” HIV.gov, www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline.

Bosh, KA, Hall, HI, Eastham, L, Daskalakis, D.C., Mermin, J.H. Estimated Annual Number of HIV Infections–United States, 1981-2019. MMWR Morb Wkly Rep. 2021 Jun 4;70(22):801-806. Doi 10.15585/mmwr.mm702a1. PMID: 34081686; PMCID: PMC8174674.

“CDC Fact Sheet: Today’s HIV/AIDS Epidemic.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Aug. 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf

Geary, Adam A. Antiblack Racism and the AIDS Epidemic State Intimacies. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Accessed October 8 2022.

“HIV and AIDS: The Basics.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-and-aids-basics.

Kleinman, Arthur. The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books, 2020. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tV_ODwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT8&dq=illness+naratives+suffering+healing+and+the+human+condition&ots=vHKpCH05FJ&sig=bEjhFgb8K9POln0DYexQAwdBclA#v=onepage&q=illness%20naratives%20suffering%20healing%20and%20the%20human%20condition&f=false

“What Are HIV and AIDS?” HIV.gov, www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids/.