What makes a captive audience a captivated audience?

by Jamie ‘Frodo’ Harkin

Traveling on an airplane hasn’t always felt like being trapped in a two-by-two-by-four shoebox, surrounded by fellow zombies, immersed in the cold glow of a myriad of blue screens. Planes once were more spacious, less stressful, and more importantly, full of laughter, conversation, and excitement… even if bored children sometimes were a little rowdy. Airtravel used to be an experience full of luxury and delight—now it’s become another example of what sociologists David Riesman, Nathan Glazer, and Reuel Denney diagnosed in 1950 as modernity’s predicament: the lonely crowd—masses of people alone in their own social and perhaps now also acoustic bubble.

With the advent of the economy class in 1958, airplane seating was rearranged to mirror what Gabriele Pedulla has described as “the true core of twentieth-century cinema”. David Flexer, a Memphis movie theater owner, fearing the impending downfall of the Golden Age of Cinema, had an idea to save his business: he pitched the idea of screening movies on flights to several airlines. Home television had brought the viewing experience into the home, just as radio had brought sound, music, and live news in the 1930’s. The advent of VCR in 1956 meant that consumers could buy or record any piece of audiovisual content, and, perhaps more importantly, the ever increasing catalog of content meant that media was constantly in competition for attention, and consumers started to individualize their media diet—a trend that has continued to this day.

Most airlines dismissed Flexer’s idea. Given the choices that viewers had grown accustomed to, they feared passengers would feel like a captive audience, trapped in some form of white noise torture chamber. Flexer countered that delivering the audio through a stethoscope-like set of headphones (designed to evoke the upward mobility of the medical professions) would give passengers a choice, and that this choice would not make them a captive audience, but a captivated one. Flexer, although he may not have known it at the time, had created the first fully immersive audio experience.

This was a taste of the future, where (practically) everybody owns headphones and goes through life listening to their own soundtrack. The (anti)social aspects alone could be enough to dissuade theater owners from promoting headphone usage, nevermind the health and safety arguments, such as a fire alarm. However, it was only in 1999 that we were introduced to Neo, and The Matrix: an entirely digital world – and the dangers of being too immersed in one. It is astonishing that it took only twenty-two years before technology progressed to the point where we’re talking about actually living in the Metaverse, with Bill Gates claiming that Zoom will be dead and gone in two-to-three years, replaced with an entirely digital environment. We can now simulate entire, virtual environments in an entirely real, 3D space, or a warzone, with shrapnel flying overhead, and bombs going off, or the rush of landing a plane amidst a hurricane in Microsoft’s Flight Simulator. We have reached a point of being able to simulate virtual environments so well that it is not a surprise to see multimillion dollar tournaments decided by who has better aural awareness. Why then, do so few movies, and even fewer movie theaters, strive to provide the same experience of total audio immersion? One must simply look at Baby Driver to see that headphones can provide Hollywood with an entirely new sensory playground.

Foremost, video games can have thousands of different sound effects playing simultaneously, combining to create a lush, dynamic, virtual audio environment. Video games do this as a way of populating the environment, much the same way that a waiting room might play generic, calming music, helping to reduce anxiety, and give the space a sense of life. This is important because it allows us to audibly perceive the environment that our avatar is in, from their point of view – to be immersed. It also means that the relative positions of the virtual sources of these sounds must also be taken into account.

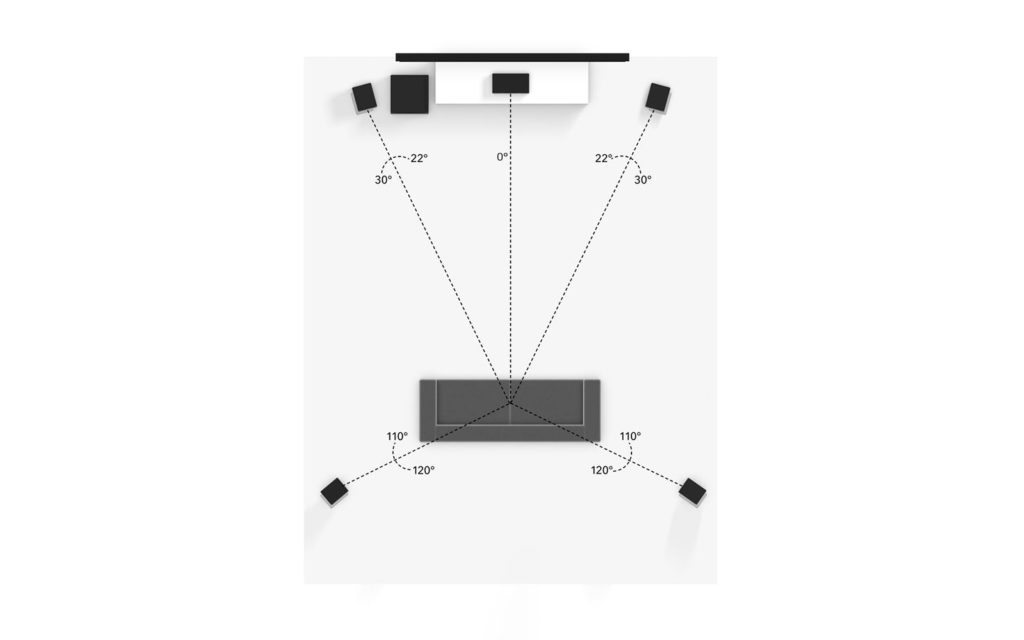

By contrast, in film, every single sound, from a pin dropping, to a machine gun firing is carefully composed, recorded, and mixed to sync up with what is happening on screen. But the output remains the same summation of signals whether from a mono-speaker, or a Dolby 7.2.3 System. However, if you consider a larger room, such as an IMAX theater, the time for the sound to travel from Side Left to Side Right can be in excess of 0.1s, almost ten times the limit of human latency perception. This creates an uncanny-valley effect in traditional surround sound loudspeaker systems, generating a minute echo and de-synchresis between the two channels. Additionally, this dilution of metadata into simply “This speaker plays this sound file at this volume”, means that the only way of denoting a moving sound is by increasing that sound in one speaker while decreasing it in another. This can cause hot (and cold) spots in the directionality of the output sound. Dolby 5.1 (or equivalent), which is still used in most theaters, is notorious for having a lack of rear or side depth, depending on the layout of the speakers themselves.

Headphones, by contrast, use an entirely different type of encoding. Imagine you are playing a war simulator, and a grenade goes off at your two o’clock. The headphones only have two, L&R, outputs, but you can tell that the explosion was in front of and to your right from the directionality of the sound. The audio drivers will take the unedited sound effect, and knowing the relative position of the grenade, perform a Fourier transform on the original file, creating a slight distortion. This slight distortion is what gives the sound a sense of direction.

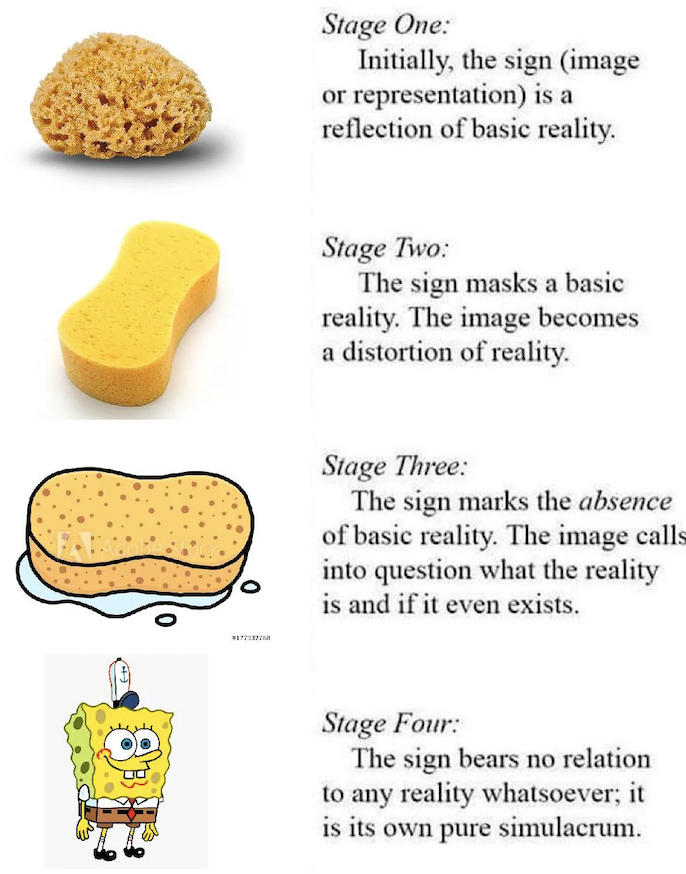

It is also extremely important to factor that in film, practically all sound effects are added in post production, unlike in video games, with each and every sound being generated dynamically by the environment in real time. Given that the vast majority of movies will now be watched on a TV (or some system with only stereo output), it is no wonder that most studios would elect to focus less on the audio, and more on the visual in post-production. In this way, despite being an actual simulation, the video game is technically a Stage 3 Simulacra, masking the absence of a profound reality, a copy with no original. Ironically, film, having been manipulated and precisely arranged to tell the audience exactly what they want to hear, is the deeper Stage 4, lacking any hyperreal aspect, a world entirely its own that we can merely observe.

Alas, it appears that, while the added immersion made possible through headphones in video games is vastly superior to that which is available through loudspeakers thanks to superior encoding and processing, we are cursed by our millennial audio recording, studio limitations, and societal factors to suffer multichannel audio in theaters a while longer. Next time you are watching a movie on a flight, choose one that you have seen in theaters or at home. Ask yourself, are you as captivated by the movie as you were then, or simply captive on the plane, trying to escape?