How stadium organists sometimes sound like silent film accompanists

by Justin Peacock

Sports themselves provide ample entertainment, but the in-stadium experience has long been enhanced with music and sound effects as well. For centuries, the organ, sometimes known as the “Queen of instruments,” had been used mainly in Churches to accompany the Sacred Rite. During the silent era, organists played on special theater organs to accompany films. After the fully electric organ was introduced in 1933, it was quickly transferred to another popular venue of entertainment: sports stadiums. These organs were first used to play the classic baseball songs like the national anthem and take me out to the ballgame. Later on during the 1960s, the ballpark organists would play songs as players walked up to the plate, known as walk-up songs. At first, these songs were always the players’ home state anthems. However, since these tunes were unknown to a majority of the audience, an innovative young organist named Nancy Faust decided to change her game.

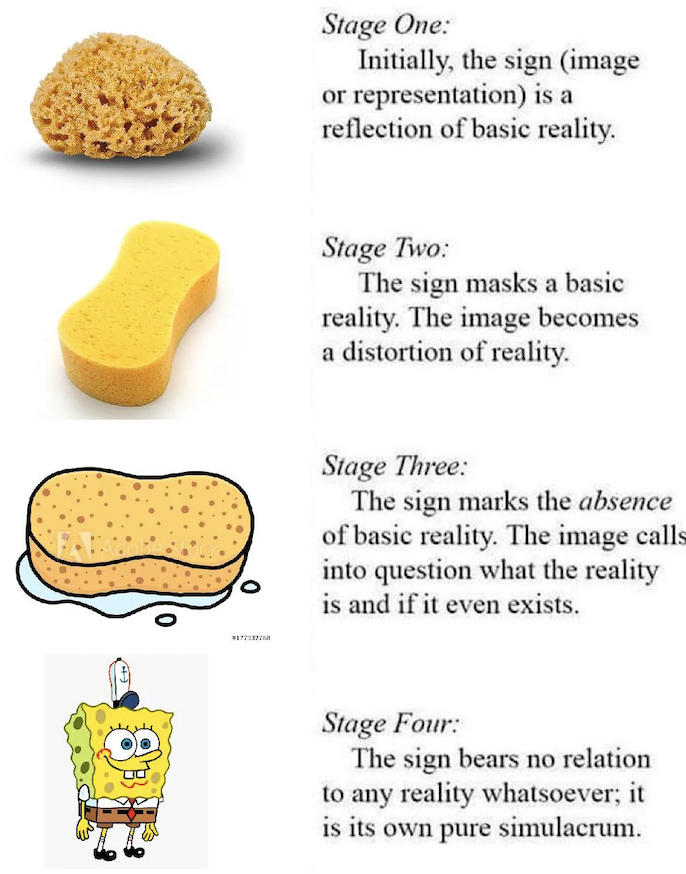

Faust was hired by the White Sox before the 1970 season to be their organist. A female organist in this era caused some uproar from the traditionalist baseball fans, but Faust didn’t care much. She was extremely talented, but didn’t read music. Instead, Faust learned to play almost any song by ear. When she didn’t know a state anthem for a walk-up song, she would call her mom and play it based on her mother’s humming. Faust realized that the state anthem songs didn’t get the crowds excited, so she started playing more modern walk-up songs that had something to do with the players’ names or numbers. She would play things like “Till You Marry Me, Bill” when Bill Melton came to the plate or “Take Five” for someone with the jersey number five. Using her creativity, Faust was able to expand the organ’s use to cover the action within the game, like playing the ominous Jaws theme when a manager takes the long walk to the mound or “The Gambler” when a player steals a base. The organ became an integral part of the fan experience at White Sox games as Nancy expanded its use to all parts of the game, and this style quickly spread around the entire league and even to other sports. She turned the organ into a tool to react to the action of the game, like playing her signature “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” late in the game when the opposing team was losing. This kind of “underscoring” was very similar to what was called during the silent era “playing the picture.” This was when organists would coordinate their musical selections with what they were seeing on the screen.

Silent films originally used entire orchestras as underscoring. While orchestras had to strictly follow their sheet music, pianists and organists could improvise. The theater organ was the the best of both worlds: one person (much less expensive than an orchestra) could fill the hall with a “symphonic” sound while also playing the picture for dramatic and comedic effect. The organist in the movie theater would either follow the studio’s cue sheet or improvise their own music to accompany the film. The underscoring of each film would vary depending on the organist’s interpretation of the film. This is similar to how the different organists would affect the audience’s view of the baseball game. Nancy Faust may think of one song to play for a player, and the Chicago Cubs’ organist may think of another. In a silent movie, the music dramatizes the action on the screen, like speeding up rhythm and tempo during an intense scene. Similarly, the ballpark organist dramatizes the action on the field with their music, like playing the Jaws theme when a coach is doing something as routine as walking out to pull his pitcher.

The most basic purpose of movies and sports is to provide entertainment to the audience. The organ adds to the atmosphere of the game, much like it did during the silent era for movies. Baseball is a very slow game, with most games lasting over three hours. The organ is a way to keep the audience entertained during all the downtime between pitches and innings. During these lulls in action the organist usually plays short tunes like “Charge” or “Let’s Go” to pump up the crowd. In playoff games or with a win on the line, these short tunes can really get the crowd standing and cheering. Faust also showed that the organ can comment on the game and the emotions felt in the crowd. By playing an ominous song with the bases loaded, the organist is heightening the fear and worry in both the pitcher and the crowd.

The organ is used differently in a Church setting than in a sports stadium or movie theater. During a mass, the organ is used to add more meaning and additional prayer through song. The loud and grand sound of the organ made it perfect for the sacred act of celebrating a Mass. The organ’s use in a baseball stadium also adds some sacred effect to the game. A baseball game is a ritual as well since the same pattern is followed every game. For decades, the same “Star-Spangled Banner” has been played before the game and the same “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” has been played during the seventh inning stretch. The fans know when to stand for these songs because they have been played at every game they’ve ever attended. Each team has some of its own special “rituals” too. The St. Louis Cardinals have a tradition every year on opening day of having the players parade around the stadium in cars. The massive Anheuser-Busch Clydesdales open the parade by pulling an old beer wagon around the stadium as the song “Here Comes the King” is played in the background by the stadium organist. The ceremony is one that connects fans across generations, since nearly every fan has attended at least one opening day throughout the years. The song has become synonymous with the team and specifically this celebration of the return of baseball. During the ceremony, the organ is used to add more meaning, not just to entertain. When fans hear this song played on the organ, it evokes a nostalgic feeling and takes them back to the first opening day they attended decades earlier.

In this way the organists do much more than just add to the entertainment or emotion of the baseball game. Sure, the songs being played can give us a laugh or add to the drama unfolding in front of us, but they also create memories for us that we associate with the music. Hearing that same sound of the organ brings us back to that feeling of sitting out in the summer sun with our family and relaxing at a baseball game. Without the organ music, every silent film would be the exact same, but the organ helps to differentiate the experience for us and create a lasting memory. Similarly, the organist’s creativity and talent can make the baseball game more special and give it more meaning than just any generic game.