The Number that Kept Fred Astaire Dancing

By Kelly Anne Huggard

Fred Astaire is probably the most famous American dancer of all times, known for his imaginative numbers in film musicals like Swing Time, Top Hat, and The Band Wagon. A little-known piece of trivia is that his “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (henceforth: PoR) for the 1946 musical Blue Skies was to be Astaire’s last dance number, and it looked like he was going out with a bang. It’s one of the most unusual and iconic dances of his legendary career, which is marked by many groundbreaking routines that came before and after PoR. Some of the most celebrated performances of his career before his first attempt at retirement involve dancing in roller skates, “dancing” a drum set, and mimicking the sound of a machine gun with the incomparable speed of his feet (all things that had never been done before). PoR is stunning in showcasing Astaire’s creative mind at the top of his game, allowing for his career to continue for 25 more years, with routines that got even more innovative. Although Astaire retired at the age of 70, he would still come back for a performance at the Oscars one year later.

Why is PoR so special? The New York Times 1946 review of the Blue Skies notes:

“Mr. A. makes his educated feet talk a persuasive language that is thrilling to conjugate. The number ends with some process-screen trickery in which a dozen or so midget Astaires back up the tapping soloist in a beautiful surge of clickety-clicks.”

On top of its “trickery,” the biggest thrill is the explosion of pure tap. Tap dancing is distinct because of the shoes that allow dancers to produce a unique sound with each movement because of the metal “taps” attached to their feet.

Tap dancing originated as a fusion of primarily Irish and African styles of dance in the late 17th century. The combination of these two cultural styles of dances is credited for tap’s unique emphasis on rhythm and sound. Tap dancing reached the height of its fame from the 1930’s through the 1950’s because of the rise of the Hollywood musical. The popularity of tap dancing during this time was largely due to the creativity and talent of performers, like Astaire. Astaire, however, was different from other stars because his style of tap dancing was influenced by ballroom dancing, giving it a more graceful appearance – an appearance of pure movement.

Tap can be performed as a solo, duo, or with a troupe (or a combination of each). While a solo allows the dancer to shine through advanced and technical choreography, the incorporation of an ensemble changes the acoustics of the number, amplifying the sound of the taps through the reproduction of sound. The louder and stronger the sound of the taps is, the grander the performance appears to be. One of the most entertaining parts of tap dancing is the vital role of sound in the performance. This is why the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the feet of the dancer – not just because of their movement, but because of their sound.

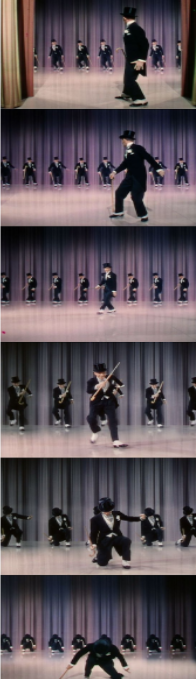

In PoR, Astaire took the typical ensemble and made it his own – literally! Although most of the number is a solo to highlight his talent, in the final minute of the song, the curtain opens to reveal a second stage filled with an ensemble of Fred Astaires. As the cluster of clones is revealed, there is a pause in the music as their taps are heard for the first time, and the tempo speeds up as they continue to dance. When the soloist Astaire differentiates his choreography from the ensemble’s, the sound of the troupe’s taps essentially becomes part of the music. As Todd Decker notes in his award winning book “Music Makes Me: Fred Astaire and Jazz,” this number is a prime example of Astaire’s “music making approach to dance making,” as the ensemble provides another layer of sound. Sound is essential to tap dancing, as every move (or mistake) can be heard, but in Astaire’s performance, there are no mistakes. The perfection of the dance naturally produces a perfection of sound.

Although the use of a cane or any prop in general is not uncommon, Astaire brings it to the next level with his cane in PoR. The cane becomes a third tap shoe as he masters the difficult rhythm of the song by hitting it against the ground to emphasize certain beats in the music. In all of his dances, especially tap numbers, rhythm was Astaire’s primary concern. The irregular tempo of this song challenged Astaire, taking him five weeks to master. The unique incorporation of the cane combined with Astaire’s natural talent to switch between fast and slow movements, turned an obstacle into part of what makes PoR so iconic.

The way in which this stunning number is designed and performed sets the stage for pure dance. There are no distractions from the dance as Astaire moves around the screen uninterrupted for over four minutes: he is aiming at pure movement. Astaire achieves pure movement by walking in a wide circle to reset before a faster dance break. These moments not only helped Astaire catch up with himself but also provide structure for the complicated choreography. The visual of the soloist Astaire combined with the ensemble of clones is simply stunning. Even though the backdrop is plain, the image and movement of the many Astaires is mesmerizing. The simple set acts as a stage for pure dance, pure movement, and pure sound.

By achieving this idea of pure dance, pure movement, and pure sound, the number takes place in Astaire’s fantastical world of pure. Although the curtain closes at the end of this number, it did not close on Astaire’s career like he intended it to. Astaire came out of retirement in 1947, with some of the most innovative performances of his career following.

Astaire further revolutionized the potential of a prop in his hat rack dance from Royal Wedding (1951). In the absence of a partner, Astaire transforms a simple prop, the hat rack, into a partner as he dances around the room with it as if he were dancing around the ballroom with Ginger Rodgers (his most famous dance partner). Royal Wedding contained another legendary Astaire performance in which he defied the laws of gravity (or so it appeared). During a solo performance of “You’re All the World to Me,” Astaire dances on the walls and ceiling of his room thanks to a rotating set. The scene is absolutely mind-blowing and stunning to watch, displaying Astaire’s infinite creativity – something that lived on even after his passing in 1987. His obituary in the New York Times praised his talent and creativity saying, “His dance numbers fit neatly within the bounds of a movie screen, but they gave the illusion of being boundless, without regard for the laws of gravity or the limitations of a set.” Astaire’s fantastical world of pure could not be confined and continues to live on through the influence of his performances.

Although Astaire’s career would have ended on a high note if he went out with PoR, how lucky are we that this number was not the end.