By Hanna Bertoldi

What is metadata?

I am constantly thinking about metadata, or the data that describes other data.

While most people may not often think about metadata, everyone who uses search tools benefits from clean, well-structured metadata.

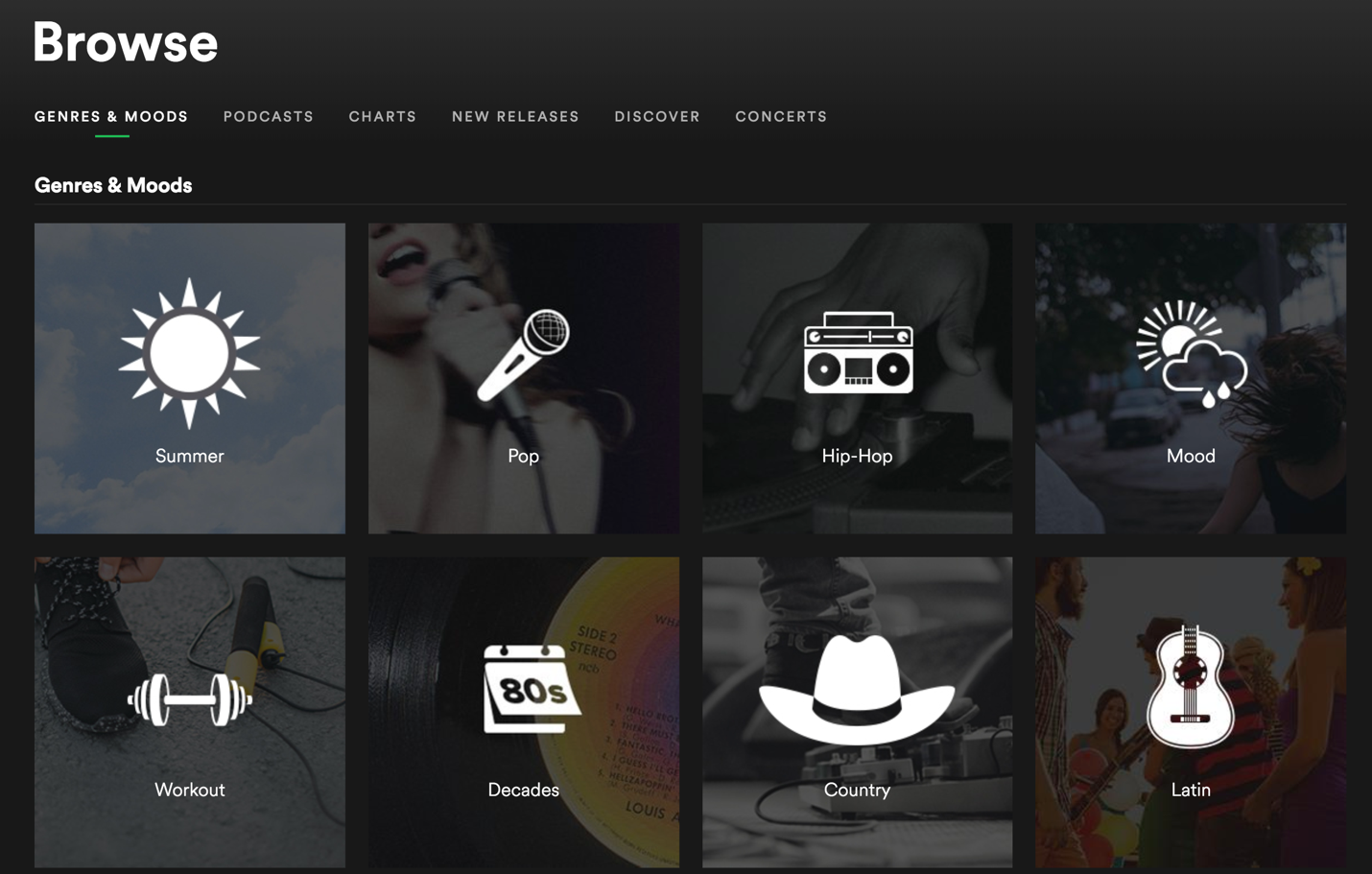

Think about a music file. Its metadata might contain the artist’s name, song title, album title, and year it was released. Spotify uses this metadata to help you find the songs you want and also to suggest music you might like. Some of these terms may be hidden from you, such as terms that describe the mood or genre of a song, but they all work in the background to create easily browsable categories.

Figure 1: Spotify browse page

Museums and metadata

Like Spotify, museums also create and use metadata, but, instead of music, the metadata describes pieces of art.

As its best self, museum metadata has the potential to bridge gaps between cultural heritage institutions and provide access beyond virtual and physical barriers. This unbounded potential can only be leveraged by using accurate and standardized metadata.

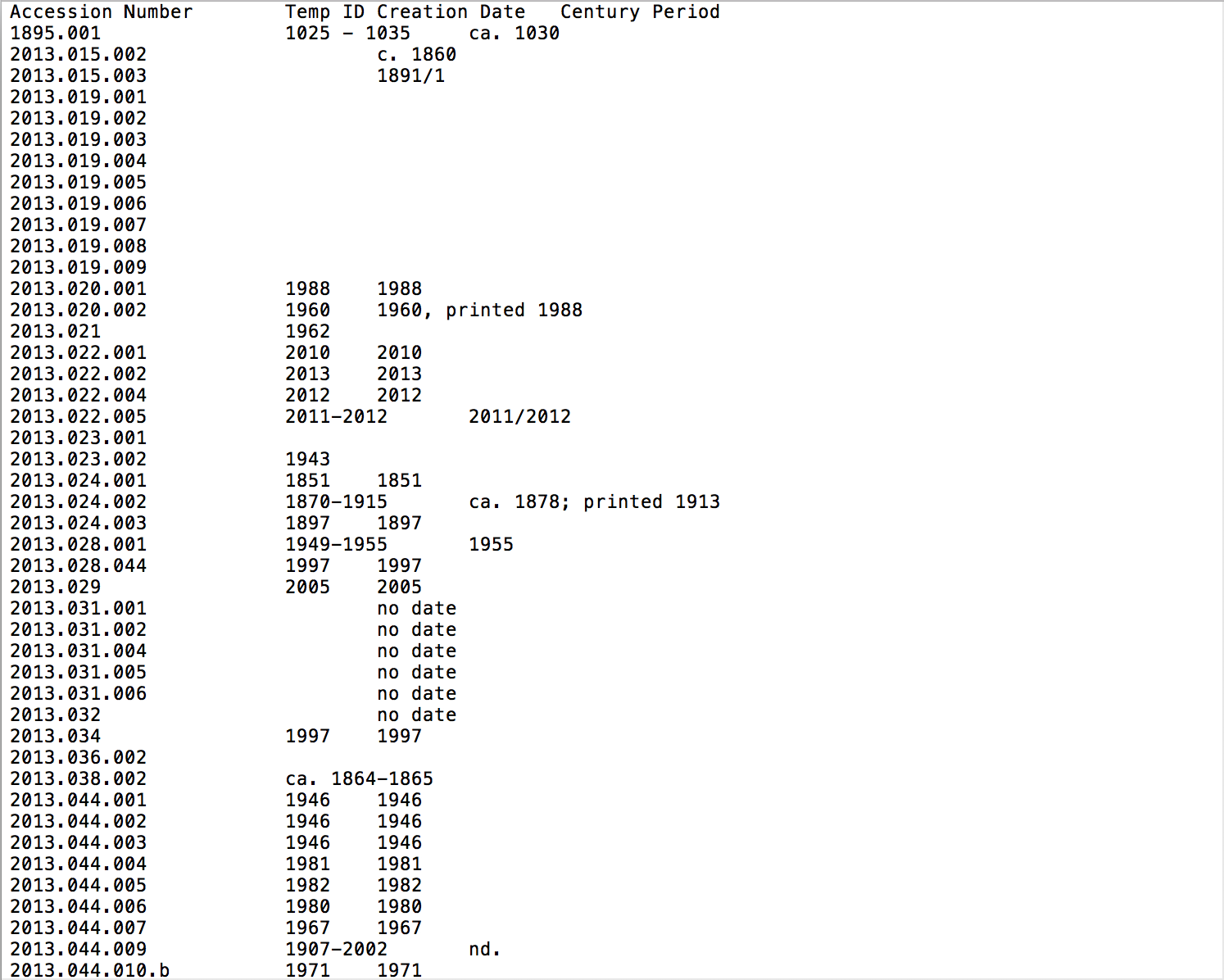

But, when I think about museum metadata, I mostly think about how messy it is. (Apparently, Spotify thinks about this too). In the screenshot below, the fields “Creation Date” and “Century” reveal some examples of data inconsistency and redundancy. For instance, you can see that at one time items without an identifiable creation date were marked with “no date” whereas others were marked with the abbreviation “n.d.” In addition, the same date is repeated in both the “Creation Date” and “Century” fields for many of these objects. These kinds of metadata errors can prevent database users from finding objects that meet their search criteria.

Figure 2: Screenshot of creation date export from EmbARK, the museum’s collections management system

Organizing the “mess” with controlled vocabularies

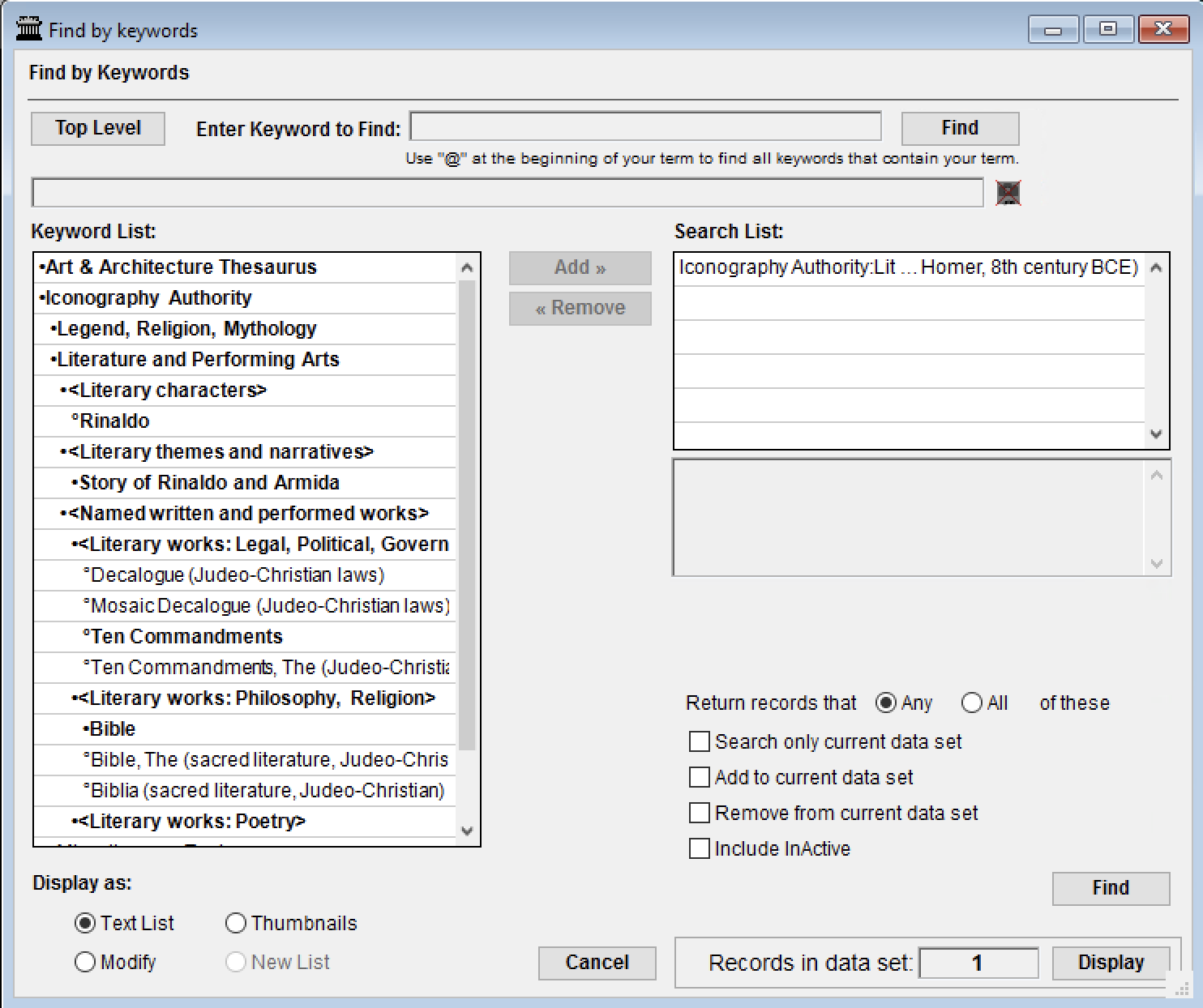

Controlled vocabularies are a critical element of creating consistent metadata. A controlled vocabulary is an organized arrangement of words and phrases used to index content and to retrieve content by browsing and searching.

If we wanted to build an application where you could search every artwork in the world, every arts organization or collector would have to agree to use the same vocabulary, or a “controlled vocabulary,” to describe their objects. We couldn’t have the Getty Museum using “Claude Monet” while the Louvre was using “Oscar-Claude Monet” to describe the artist that painted water lilies in the nineteenth century. They would have to agree on the same version of the artist’s name.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Getty Research Institute started developing controlled vocabularies for cataloging visual arts and cultural heritage. The terms and associated information in the Getty Vocabularies are valued as authoritative because they are derived from published sources and represent current research and usage in art history and cultural heritage communities.

In short, the Getty Vocabularies provide a convenient system for mapping data, without spending a lot of wasted time reinventing what already exists.

Figure 3: Searching EmbARK, the museum’s collections management system, by subject terms

Applying the Getty Vocabularies to Snite Museum collections

Now, back to the messy data part.

The Snite Museum of Art has been thinking about subject retrieval for quite a while. Perhaps as early as 2010, Snite curators began cataloging works of art with subject terms or keywords. This metadata allows curators to search for things about an object, such as who or what is depicted. Unfortunately, these terms were used without standardization.

Building off of the curators’ previous work, my goal as Collections Database Coordinator was to transform these subject terms or keywords so that they fit within the Getty Vocabularies. On a superficial level, this process has helped to clean up things such as errors in spelling and inconsistencies with formatting and style. On a deeper level, the process created relationships among objects and increased discoverability.

Figure 4: Unidentified photographer, Geisha in a Ricksha, Japan, ca. 1880-1890, albumen silver print with applied color. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Acquired with funds provided by Robert E. (ND ’63) and Beverly (SMC ‘63) O’Grady, 2008.054.002.

Such immediate improvements in discoverability are a result of the way Getty Vocabularies are structured: as hierarchical thesauri.

Getty Vocabularies are hierarchical to allow similar objects to be grouped together. For example, you want to discover all of the works in your collection that depict transportation.

- You would search the term “vehicles” and return all objects that use the word “vehicles”

- You would also return any objects with more specific terms that are organized underneath the term “vehicles” such as “milk carts,” “fire engines,” “wheelbarrows,” etc.

With the hierarchical organization, you would not have to think of or know all the various subsets of vehicles.

Getty Vocabularies are also thesauri because they connect variable terms that express the same concept. It doesn’t matter if you search for “ricksha,” “rickshaws,” or the French pousse-pousse — the computer will always know what you mean.

By leveraging the research that Getty has done, I can make the Snite collections more usable to a diverse audience.

Contributing to Getty Vocabularies to pave the way for MARBLE

Creating a thesaurus for the entirety of human knowledge is a big task, so Getty relies on contributions from the user community to expand their vocabularies.

I’ve come across many terms that weren’t part of the Getty Vocabularies in the Snite Museum’s database. These terms could have stayed “local,” which would have made the information only available to our staff. Our purpose, however, is to make the Museum’s collections searchable alongside the University Archives, Rare Books & Special Collections, and other cultural heritage materials on Notre Dame’s campus.

To make sure our collections are cataloged in a way that computers can understand, I needed to add these missing terms to the Getty Vocabularies.

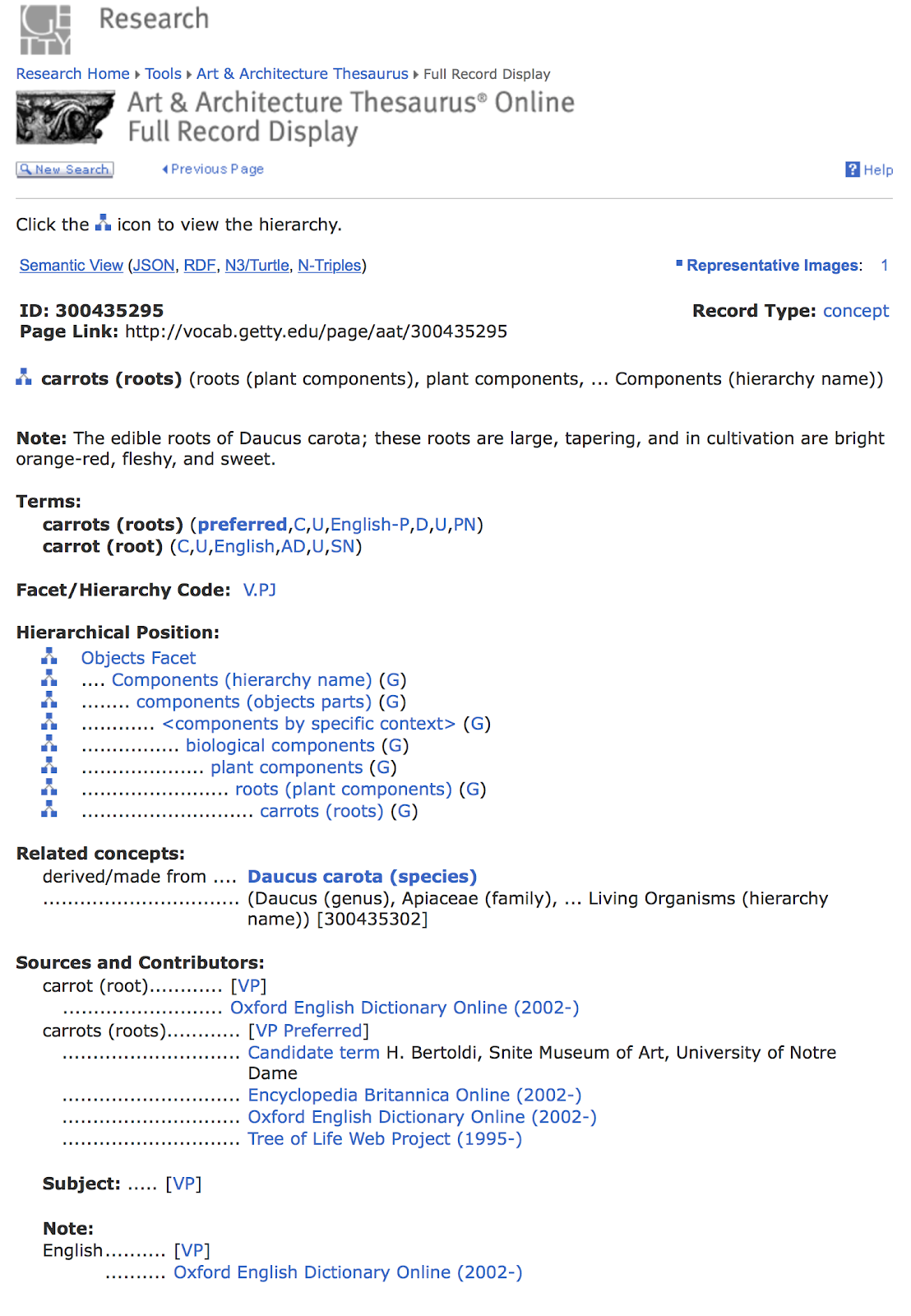

Figure 5: Record for carrots created from my submission

Using the Snite’s collections, I have contributed over 80 terms to the Getty Vocabularies within the past year. The terms are reviewed and published so that they can be used by others. Terms like these will be a core piece of the MARBLE website so that users can search across different kinds of collections through a single search portal.

MARBLE: Combining controlled vocabularies

The Getty Vocabularies are just one example of a controlled vocabulary. Other vocabularies are appropriate for cataloguing different kinds of materials, such as the Library of Congress subject terms for print materials or the National Institute for Health’s Medical Subject Headings for biomedical information. Although we don’t have many biomedical items slated for inclusion in the MARBLE site, we will need to accommodate the different controlled vocabularies used by art museum, library, and archival catalogers.

Our Metadata Team is currently working on a solution for combining the authoritative vocabularies used by the Hesburgh Libraries and the Snite Museum. We’ve considered everything from enforcing a singular controlled vocabulary across collections to experimenting with Linked Open Data solutions that would allow us to combine different vocabularies using emerging web technologies. Cleaning up the Snite’s subject terms is just the first step towards revealing metadata’s best self. Stay tuned for future posts on our progress.

While our immediate aim is to improve discoverability, our future aim is to provide some of the same services as Spotify. Users may not be aware that controlled vocabularies are working to suggest artworks or texts that might be of interest to them. My hope is that specific metadata clean up will seamlessly improve searching and browsing on a large scale.