By Peggy Griesinger and Mikala Narlock

Digital collections are deceptive; when users turn to online platforms to access content, the amount of work required to provide uninterrupted access to digital materials is not always obvious or clear. One aspect of this work is taken care of by our software developers and product owners, who work to ensure that the interface and user experience are as simple and effective as possible to our end-users. While that aspect of the work is handled, other library staff and faculty must then take on the not insignificant job of digitizing, describing, and making accessible library, archive, and museum materials before they can be accessed online. While it is beyond the scope of this blog post to discuss the nuances and particulars of digital collections writ large, we will briefly describe how digital collections are produced at Hesburgh Libraries, why workflows are so crucial, and how we are focusing on sustainability to ensure the long-term success of this type of work.

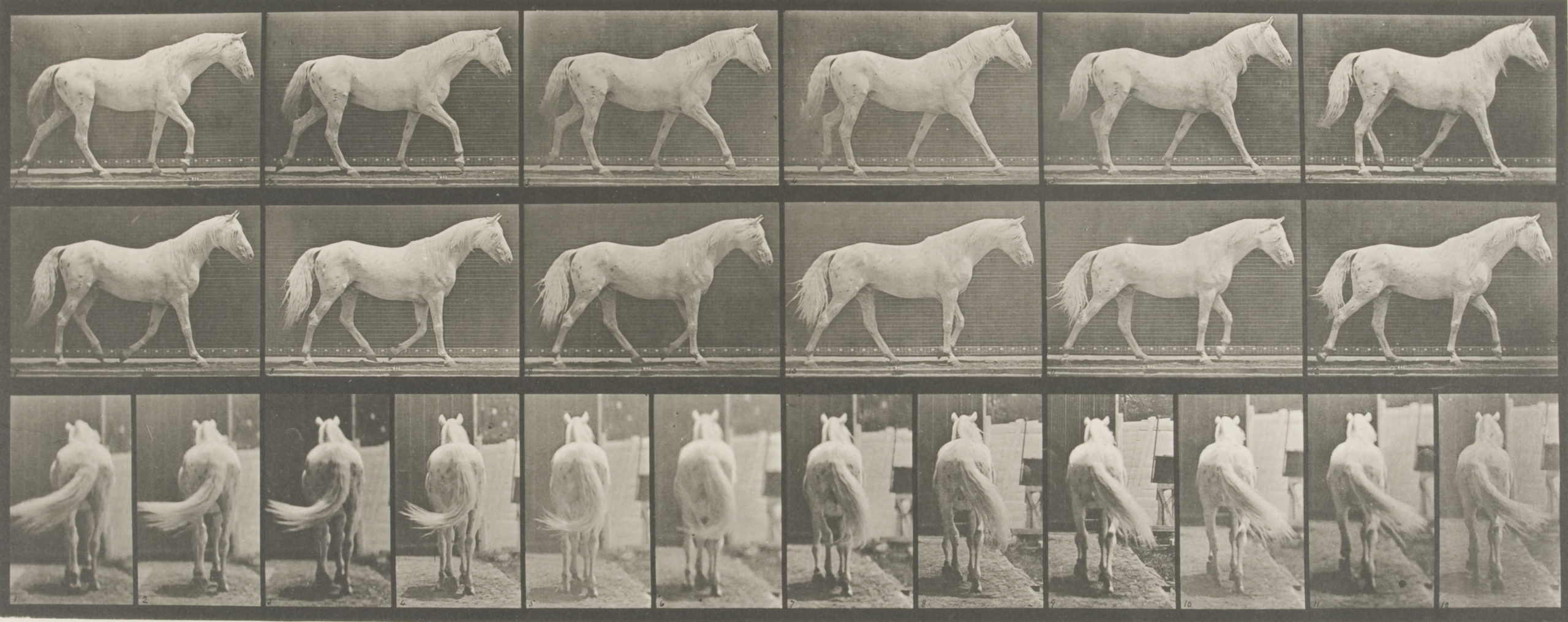

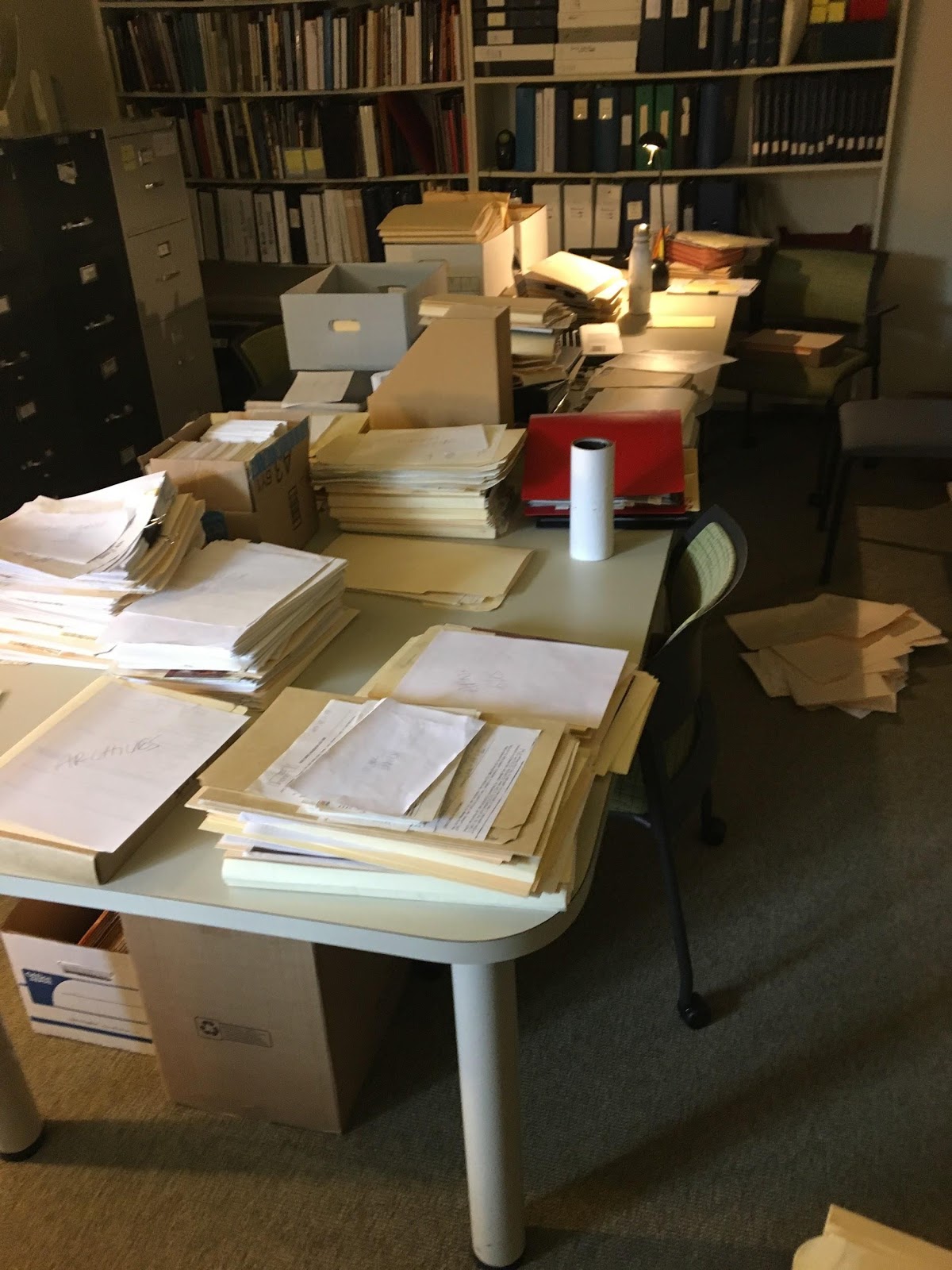

The Workflow Team hard at work.

About Digital Collection Management at Hesburgh Libraries

At Hesburgh Libraries, the process of creating digital collections is managed by a team of ‘Case Managers,’ individuals responsible for overseeing projects and ensuring that collections are processed efficiently and following standardized processes. Established in 2018, this low-tech approach to workflow management is based on project management principles to ensure the timely completion of requests. The case manager provides guidance and support for digital collections, and serves as a liaison between units. As Case Managers, we are tasked with working with subject selectors to identify collections, triage requests, and determine how best to digitize the content. Using modular workflow components, such as “Send to Conservation,” or “Route to Metadata Services,” we can build custom workflows to ensure all collections receive the appropriate care without stalling in a bottleneck area. Additionally, Case Managers serve as the primary contact for all project participants, and keep everyone apprised of progress and hindrances. Every digital collection, ranging in complexity and size from one diary to hundreds of boxes, is assigned a Case Manager to ensure there is always formal project oversight and that collections are not left behind in the event of personnel change. This team of case managers is called the Digital Collections Oversight Team (DCOT).

The oversight provided by DCOT is crucial to avoiding stumbling blocks in the complex process of creating digital surrogates for collection materials. Potential stumbling blocks include, but are not limited to: the digitization itself; additional processing requirements, such as in the case of archival collections; physical conservation needed to ensure materials are not damaged in the digitization process; additional descriptive information requiring the intervention of experienced catalogers; copyright review; and other concerns unique to particular collections, such as a need to be able to batch-process catalog records or transport materials to a vendor. Every collection calls for a slightly different workflow, but, at the same time, each project provides more experience and practice for our team to more comprehensively understand digital collections workflows at the Libraries. Given efforts at Hesburgh Libraries to identify a Libraries-wide digital collections platform, we are aware that the workflows we develop and document will be crucial for effectively creating and delivering digital content in ongoing and future efforts, including the MARBLE site.

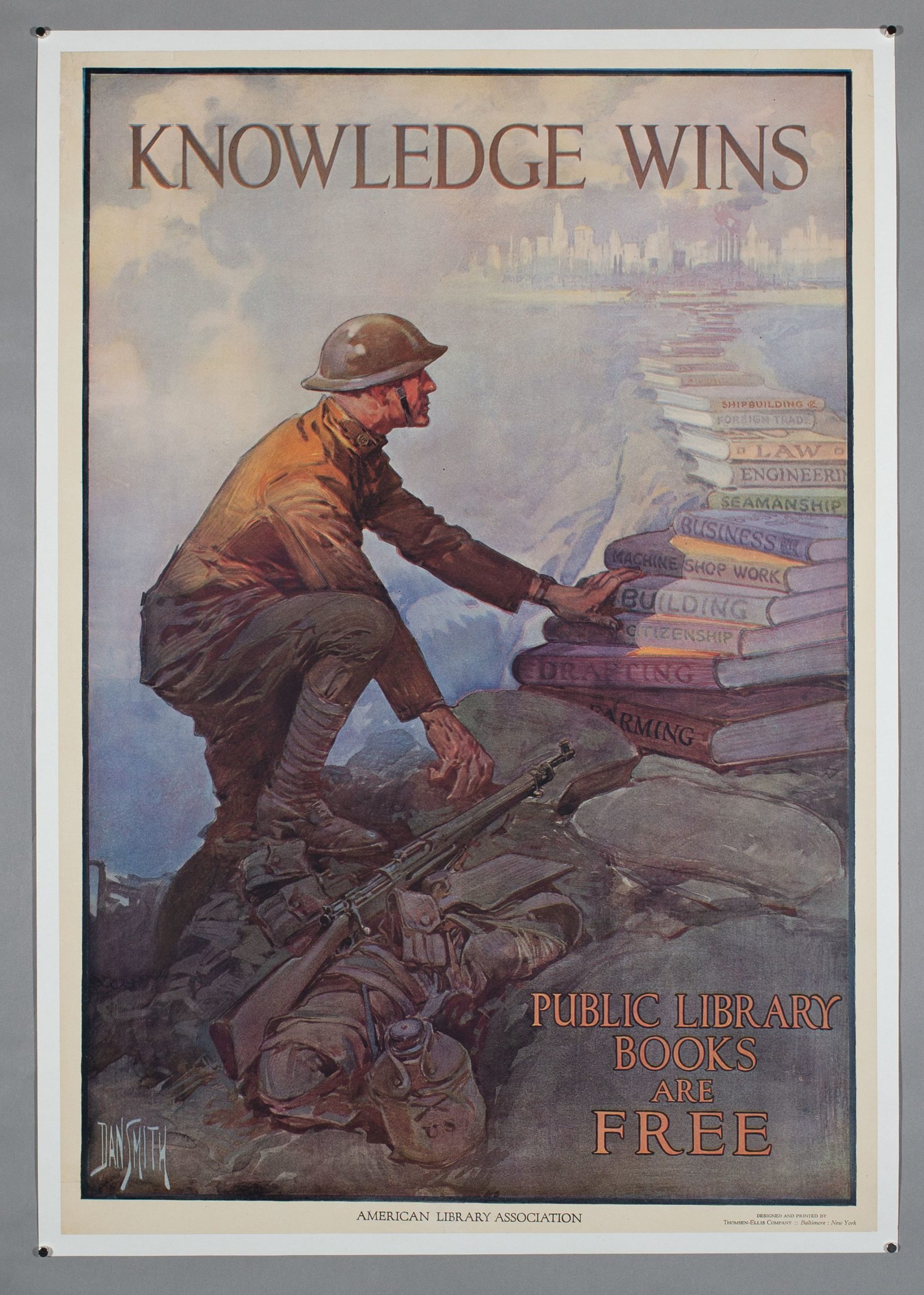

A recently added World War I-era poster proclaiming the importance of libraries .

Workflows for MARBLE

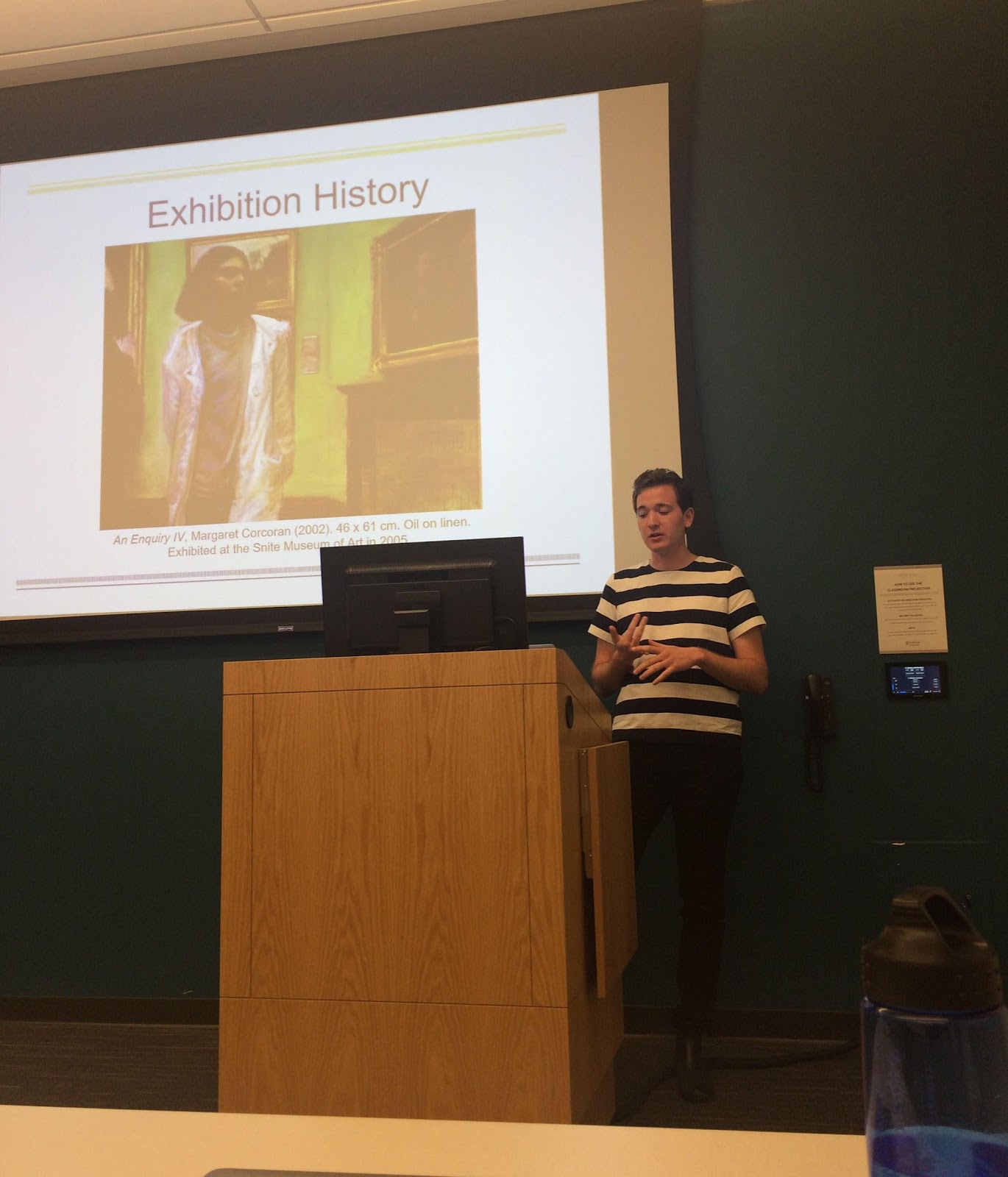

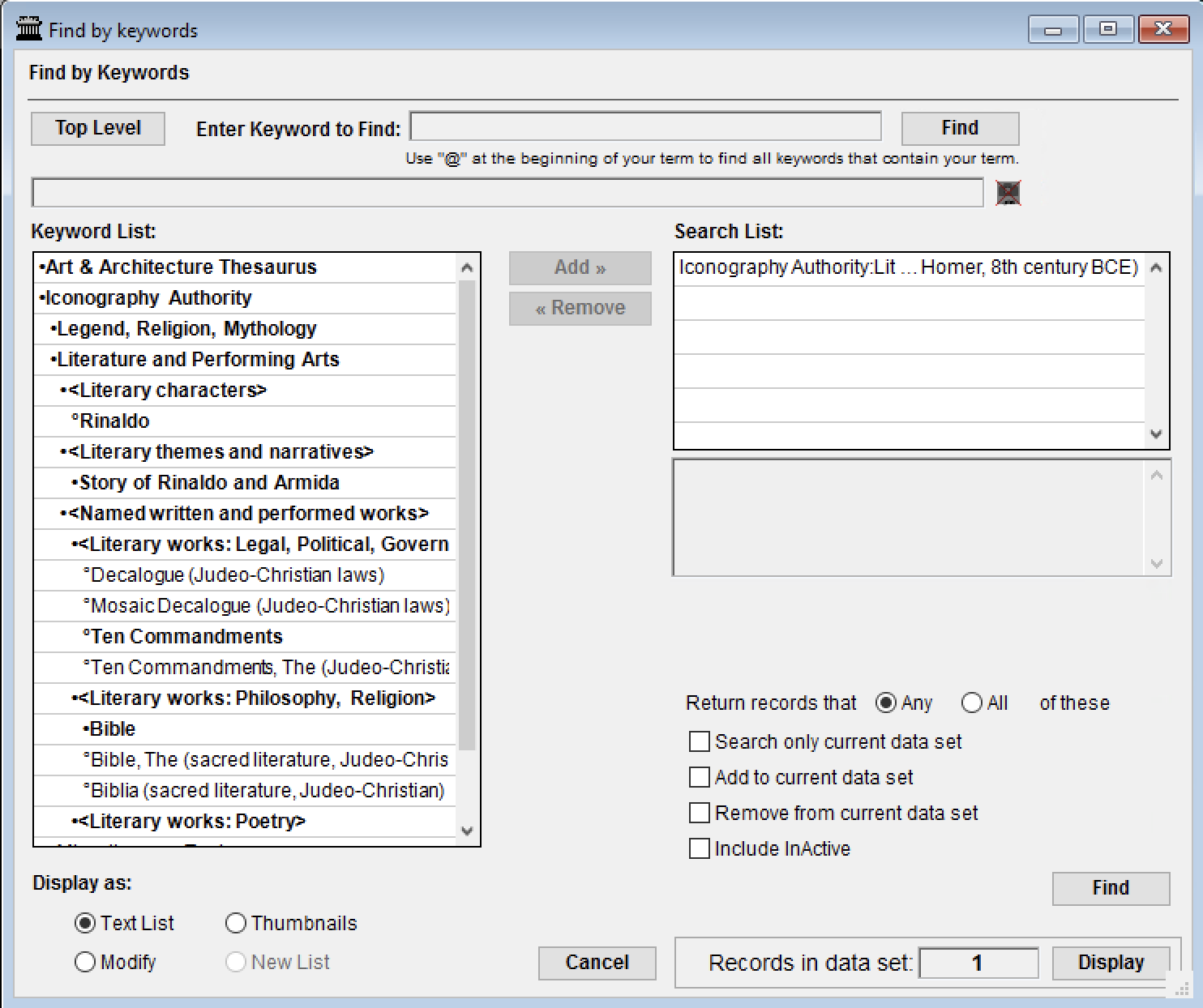

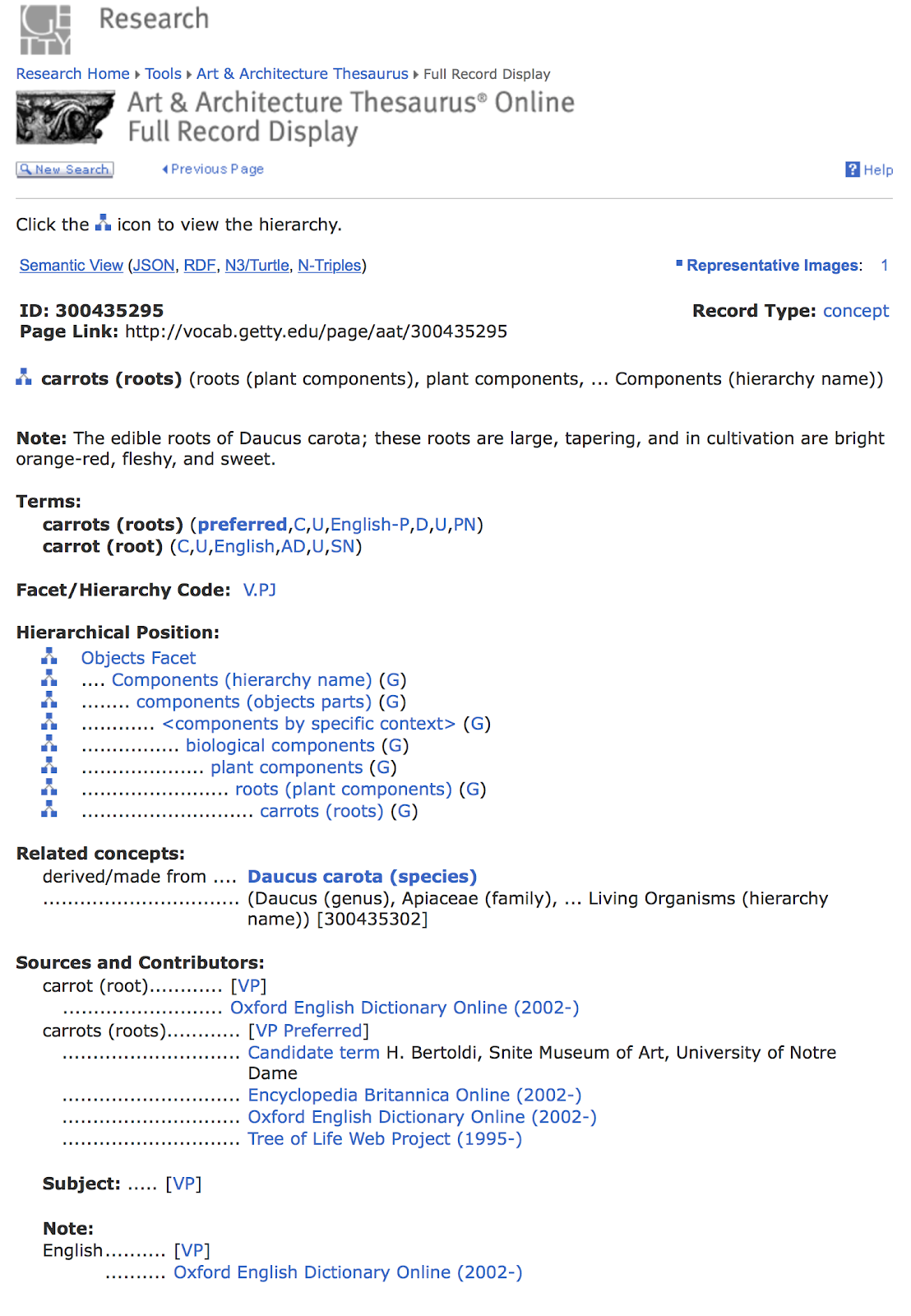

In keeping with the collaborative spirit of the MARBLE project, we have focused on simplifying our workflows across departments and aligning processes between the library and the museum. In reducing the number of discrepancies between the workflows, we can automate processes and simplify the burden of labor on Case Managers and other stakeholders. We started this effort by sketching out anticipated workflows, taking into account variables such as: the existence of descriptive metadata, whether an item was a library or archival material type, and the custodial department responsible for the item. During this process, it became apparent that, despite anticipated discrepancies in workflows, many of our procedures were already aligned, even if we sometimes used different terms to explain related concepts. Additionally, the work of our developers has allowed us to align our existing workflows in a way that will enable each unit to continue using its own best practices while still automating the process of content ingest into MARBLE in a consistent and standardized manner. Building this ability on top of our existing systems will allow us to continue using workflows that are effective for each unit while at the same time easing the process of conciliating diverse collections so they can be accessed on a shared platform like MARBLE.

Ensuring Sustainability

Workflows for creating and managing digital content are critical to the success of any digital library. We expect demand for digital facsimiles to increase as traffic to the MARBLE site continues to grow, especially during this period of heavy reliance on online classes and virtual instruction. Our team is looking to grow sustainably, and ensure that many people, particularly those embedded in custodial departments, are able to upload content to the MARBLE site without confusion, significant efforts, and bottlenecks. Our overall focus is on making use of existing expertise, staffing, and workflows while also ensuring those disparate pieces work well together and lead to solutions, like the MARBLE project, that make the cultural heritage of Notre Dame institutions more widely accessible.