By Abigail Shelton

At universities, there is often the desire for project partnerships, but differing organizational priorities sometimes inhibit true, long-term collaboration. The question is, how can two independent campus departments work effectively together toward sustainable outcomes?

At Notre Dame, the leadership for Hesburgh Libraries and the Snite Museum of Art started by identifying a project with shared goals that aligned with institutional priorities.

Securing funding was the next step. The partners jointly submitted a grant proposal for a three-year project, the success of which depended on multiple stakeholders working together to develop collaborative solutions over time. In December 2017, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded Notre Dame’s project to create a unified discovery and access platform for library and museum collections.

It was clear early on that the project’s complexities demanded that technical and subject matter experts from both organizations had appropriate representation and a framework to sustain what would become a new, shared campus service. Ultimately, strong project management, persistent outreach, ongoing communication, and cross-departmental teams became important ingredients to collaboration.

Early Planning and Outreach

Project organizers set some basic guidelines for collaboration: each unit would receive one grant-funded position; team members would regularly work in each other’s spaces; the project team would meet every quarter for an update; and staff would tour and gain familiarity with each others’ collections.

These structures worked well for those directly involved in the project’s work, but there was still a question of how to ensure the diverse community of experts from the museum and library were also involved and invested over the long-term.

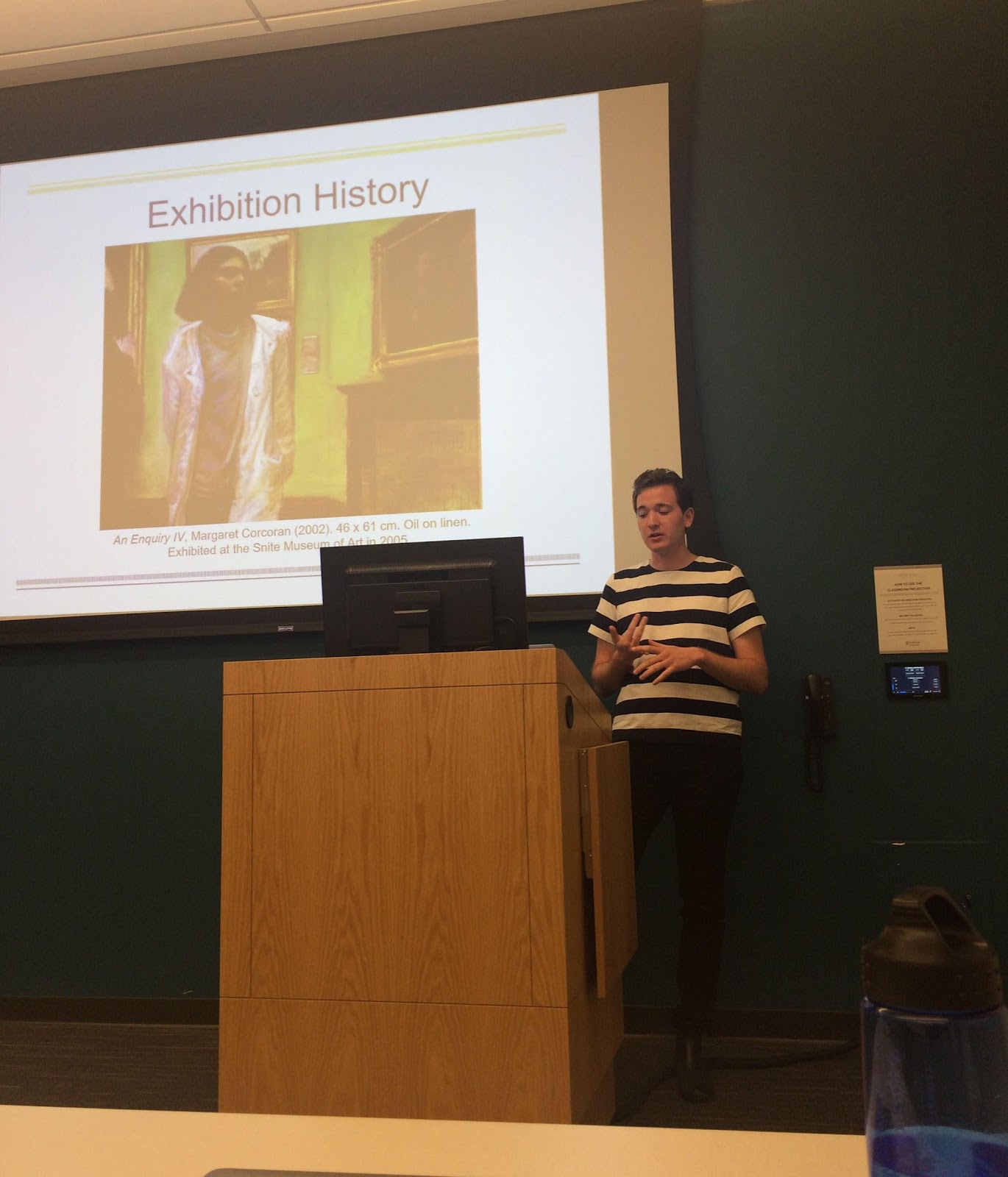

The first strategy was targeted outreach by the Outreach Specialist who met one-on-one with library and museum curators, archivists, subject specialists, metadata librarians, and other stakeholders. Project staff also held quarterly meetings open to all library and museum personnel to hear project updates, ask questions, and learn about next steps. The outreach specialist and project manager also began working towards a website and blog to be a communication resource for staff as well as the wider world.

The Content Team Forms

As 2019 approached, the core team realized that they would also need needed investment from collections experts to make decisions about digital content. They invited curators from the Snite Museum of Art, archivists from University Archives, curators from Rare Books and Special Collections, and librarians from Hesburgh Libraries to form the Content Team. Led by a curator from Rare Books and Special Collections, this group began to meet regularly to select representative content from across collections for inclusion in the platform.

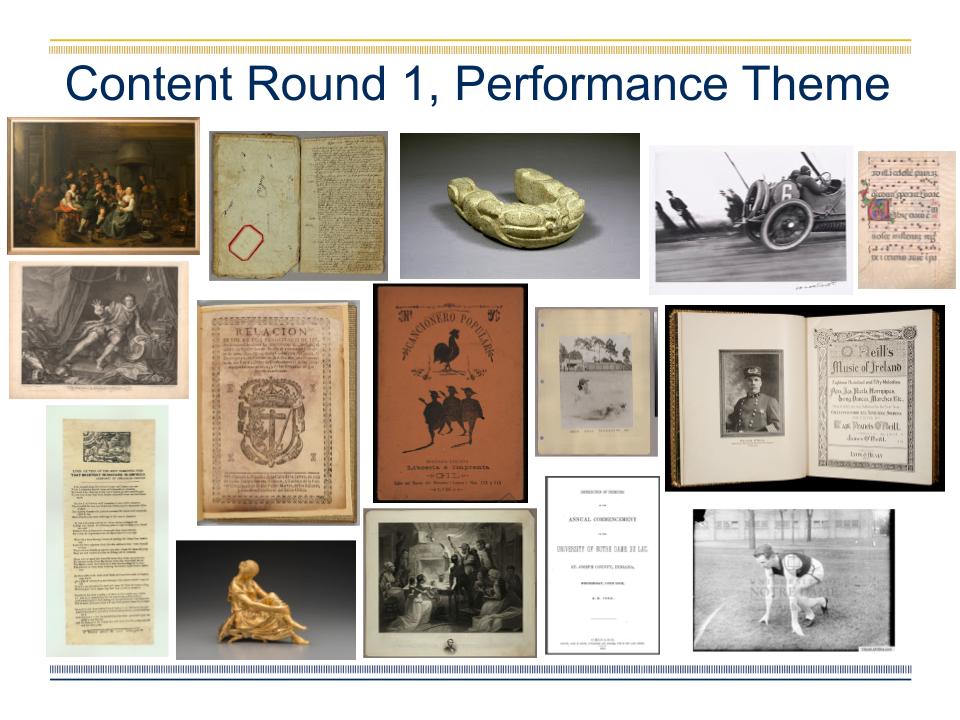

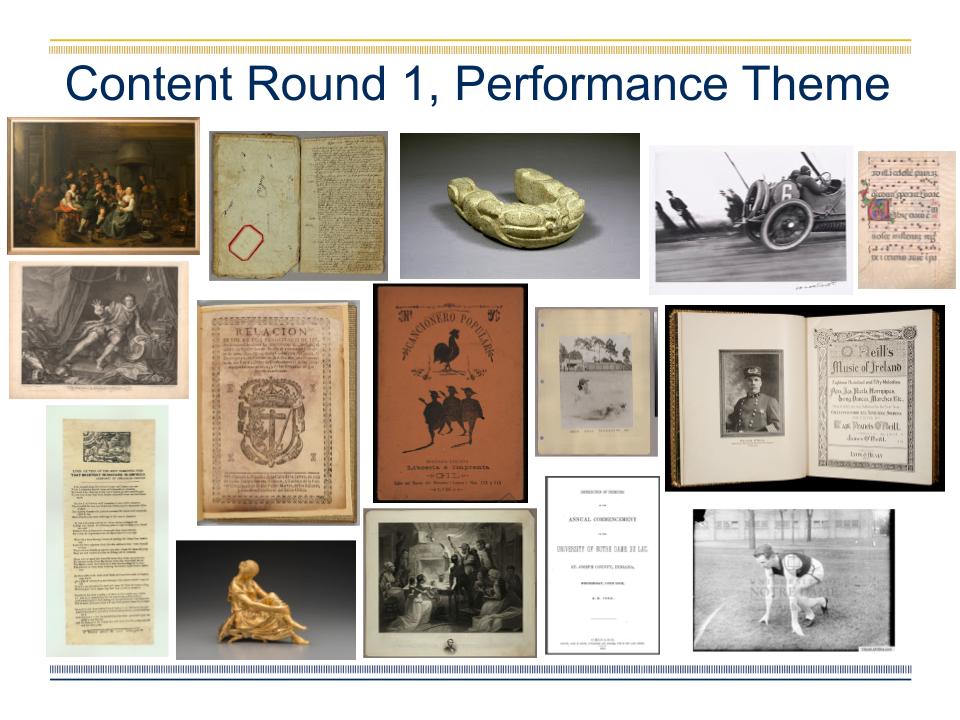

This team organized the first batch of content around a theme that could encompass materials from the archives, library, and museum. In choosing performance as the opening topic, curators drew from the library’s rich sports collections, Irish music broadsides, and religious materials. Museum specialists selected objects from the Meso-American collections, prints depicting historic theater performances, and a portrait of one of the greatest nineteenth-century French actors, among others. Archives staff selected Notre Dame student jazz festival programs, historic commencement programs, and speeches from the University’s beloved past president, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh.

Sample of selected content

The team was sure to choose diverse formats — from photographs and print materials to three-dimensional objects and paintings — in order to challenge the next two teams in the chain: Workflow Team and Metadata Team.

From Content to Workflow and Metadata

After forming the Content Team, the core project team created the Workflow Team to empower those who would ultimately implement the project workflows. Once the Content Team handed off the first test batch, the Workflow Team set out to take the raw material and make it accessible online.

The first challenge was to identify the source systems for the digital assets and associated information for the pilot collections. Hesburgh Libraries and the Snite Museum of Art have been digitizing their rare materials for conservation, research, and teaching purposes over the course of several decades. As a result, digital images are scattered across a range of storage locations including file folders, hard drives, and cloud-based storage systems.

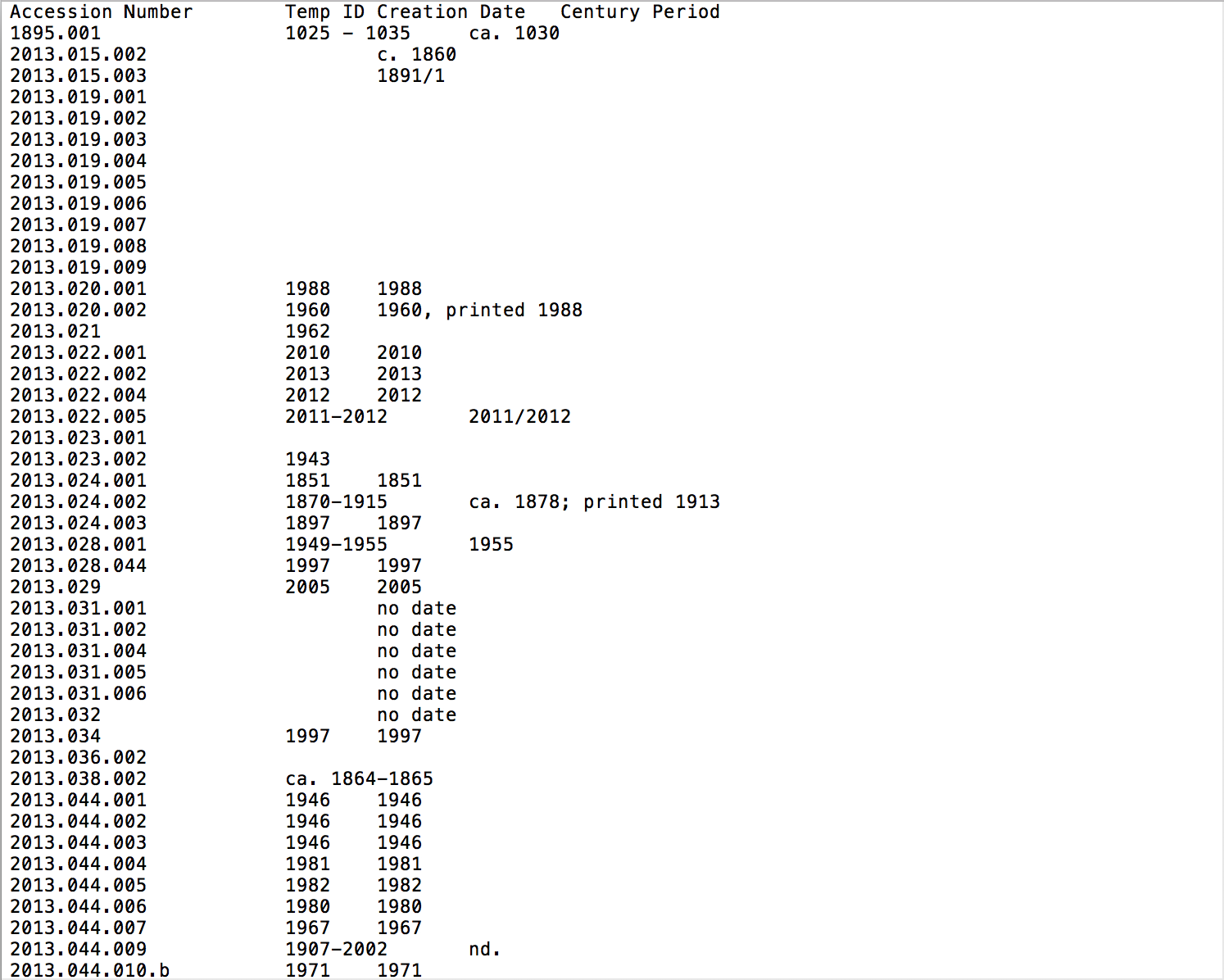

The associated metadata is also dispersed across several locations, such as an integrated library system (ILS), proprietary museum database, ArchivesSpace (finding aids for archival materials), standalone websites, spreadsheets, our institutional repository, printed catalogs, digital exhibits, museum object files, and most importantly, the minds of our subject specialists.

Once the Workflow Team identified the source systems, they began talking to the gatekeepers about formats and access. The team is currently working towards moving digital assets and metadata from their current locations into a directory structure, through a IIIF pipeline, into the search index, and ultimately to the user interface.

Workflow Team meeting and diagrams

A Metadata Team was also started to engage experts from each organization to make collaborative decisions about how to manage metadata across the platform. They work in tandem with the Workflow and Content Teams to plan for metadata remediation and mapping.

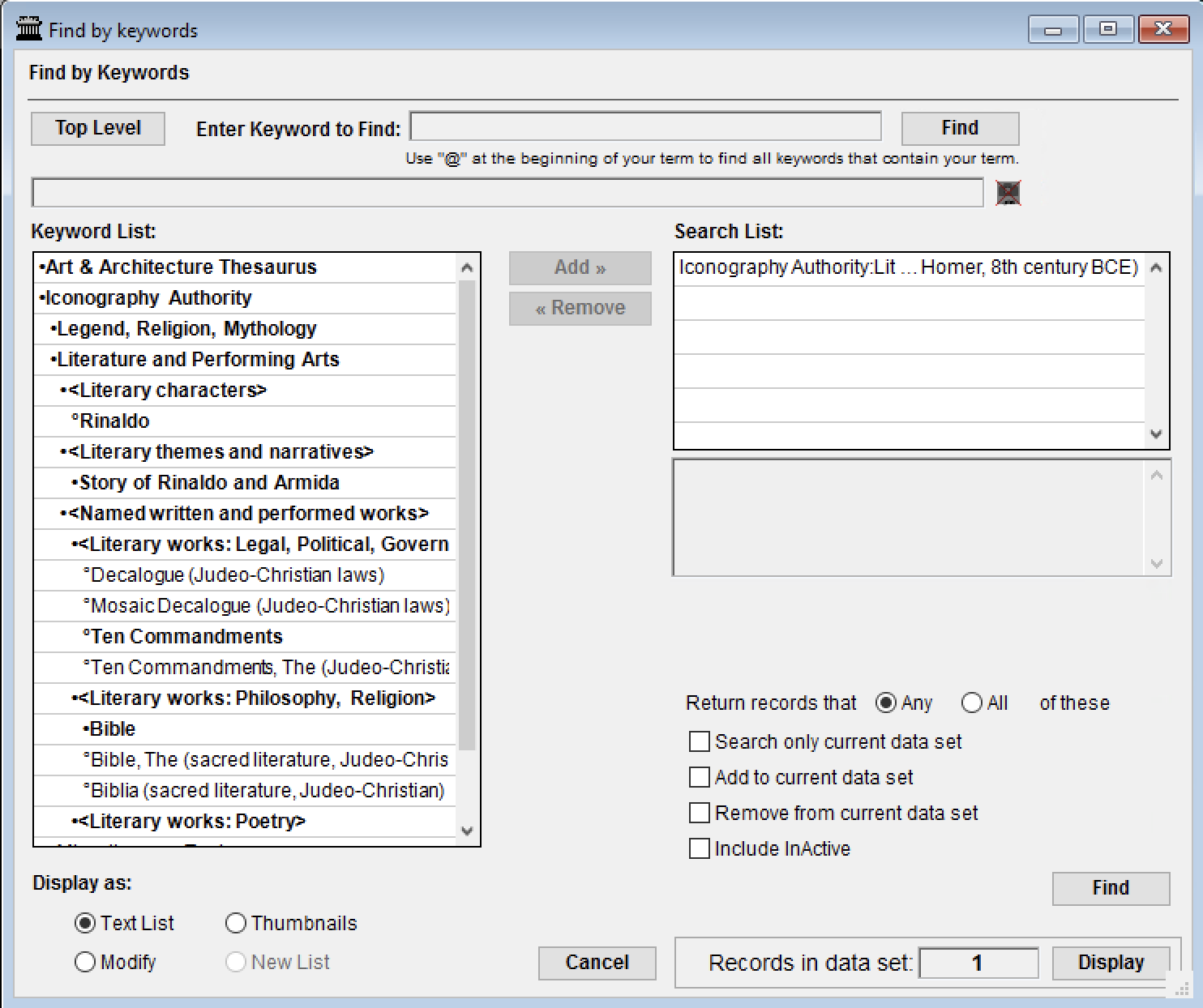

One of their greatest challenges is devising a solution that enables a robust search across archives, museum, and library collections when each project partner uses different data standards and formats.

The team has been working on better understanding how each partner is cataloging their items and storing their metadata. In the next phase of the project, the team plans to make recommendations for how to reconcile subject term differences and develop basic metadata profiles. They will also document how to map museum and archival metadata into a unified search index so that users can search across the repositories’ holdings.

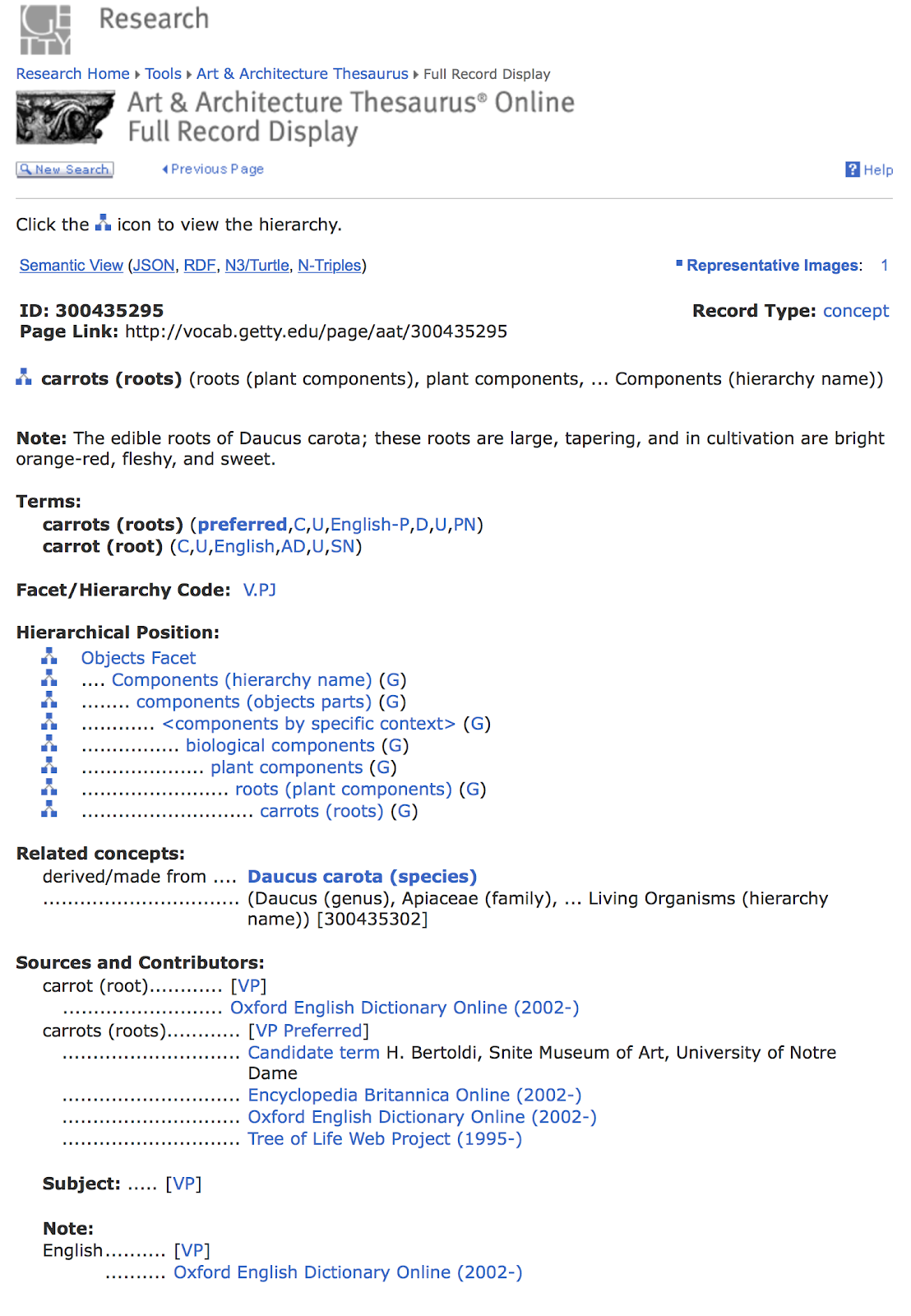

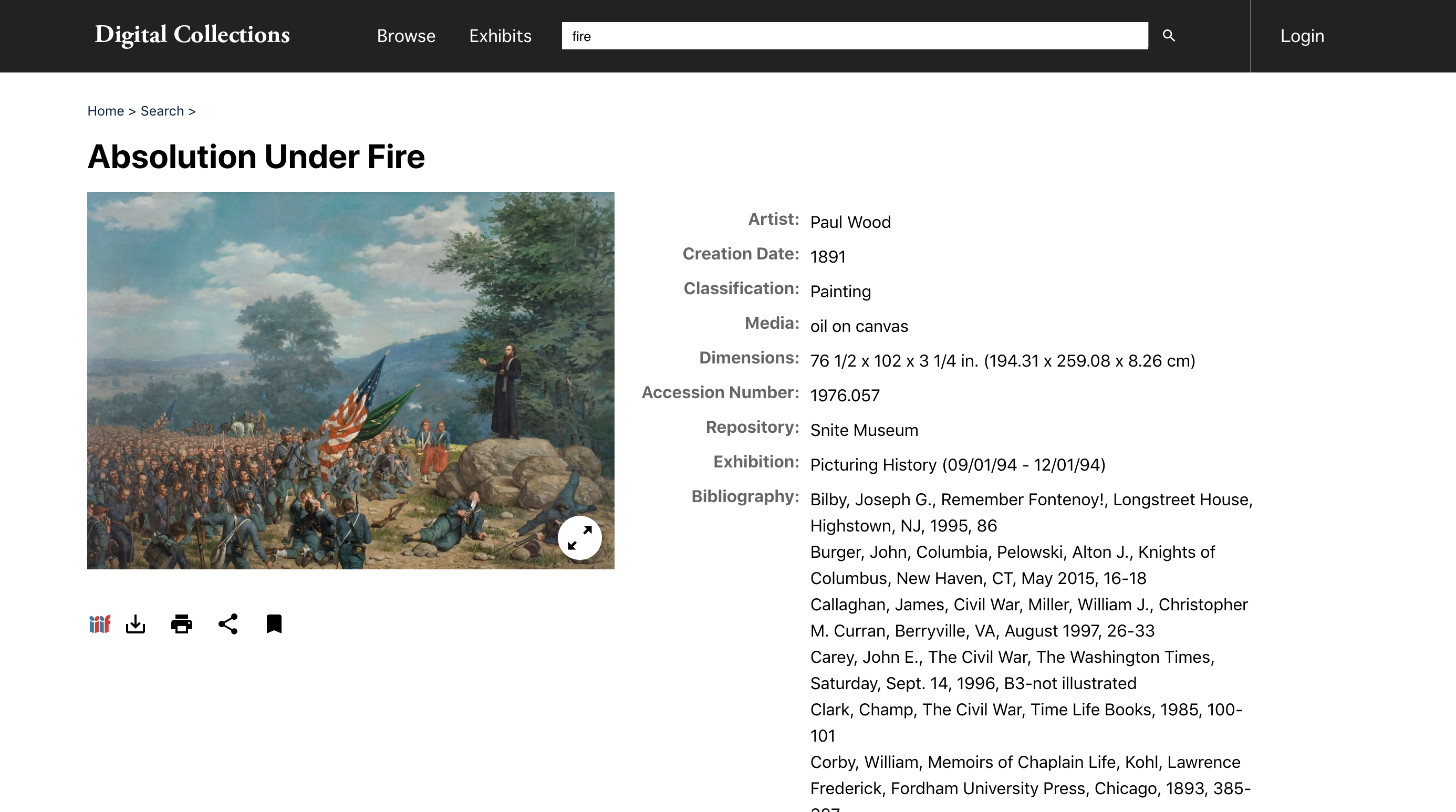

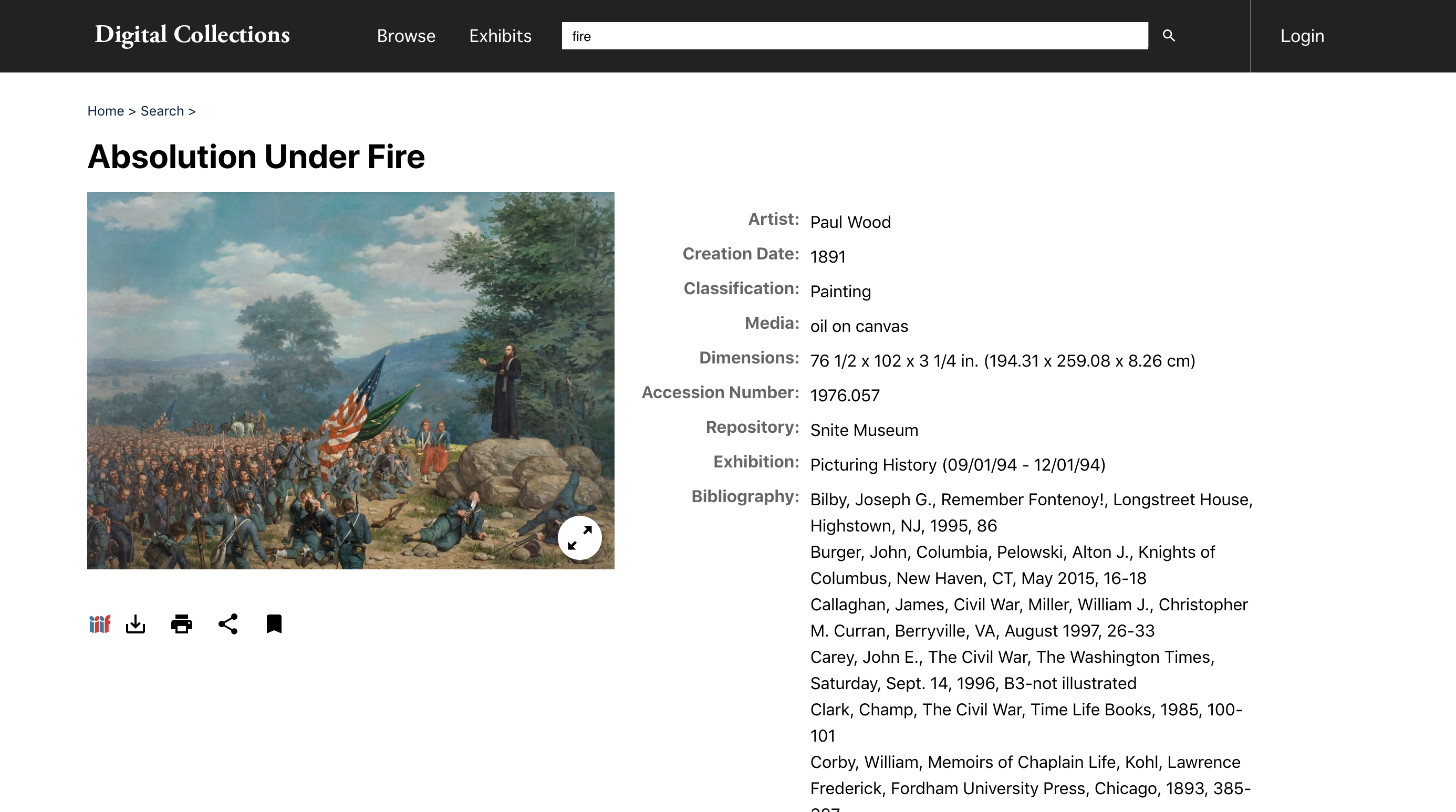

Metadata display for painting from Snite Museum of Art

The Foundation of Collaboration

At the onset, the core team understood that the software would only as successful as the collaboration and the long-term commitment of the people behind it. Opportunities for staff in the museum, library, and archives to better understand each others’ collections, professional best practices, and workflows were intentionally designed to strengthen the partnership between the two campus departments.

Already, members of these teams have begun to learn the best practices of others. Walk into a Workflow Team meeting and you might hear a metadata librarian talking about museum software. Sit down with the Metadata Team and the museum database coordinator might tell you all about archival finding aids.

The Content, Metadata, and Workflow Teams have limited project charters — their mandate is to tackle specific use-cases and questions within the three-year scope of the grant. However, the investment in developing shared understanding and vision through teamwork has cemented working relationships that will thrive after the grant period ends. This will be critical to ensuring the success of the platform well beyond the initial development and launch.