Early in the 1880’s Professor James F. Edwards, librarian of the University of Notre Dame, aware that irreplaceable items pertaining to the history of Catholicism in America were constantly in danger of being lost through neglect, carelessness or willful destruction, began to implement a plan which he had conceived for establishing at Notre Dame a national center for Catholic historical materials. The frail but hard-working Edwards set about acquiring all kinds of relevant items, including relics and portraits of the bishops and other missionary clergymen, a reference library of printed materials, and an extensive manuscript collection. Notre Dame’s ambitious scheme for an official American Catholic archives had to be given up in 1918 when Canon Law was changed to require each bishop to maintain his own archives.

James Edwards acquired the The Archdiocese of New Orleans Collection in the 1890s and it remains a very important collection in the University Archives. The first two items in the collection are dated 1576 and 1633 and are two of the oldest documents in the University Archives. There are a number of items for the period from 1708 to 1783, but the great bulk of material pertains to the years 1786 through 1803. Consulted mainly by historians of the Catholic Church, this collections also proves useful also to secular historians because of the close connection between Church and State which existed during both the French and Spanish colonial regimes in Louisiana and Florida.

1633

1633

De Perea, el Padre Fray Estevan, Guardian of the Province of New Mexico

to Very Rev. Francis de Apodaca, Commissary General of all New Spain,

of the order of St. Francis.

In the 1960s, with the aid of a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the University Archives microfilmed the Records of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas, 1576-1803, containing the early documents from the New Orleans collection. A digital edition is now available to researchers online with abstracts in English summarizing the original Spanish, French, and Latin documents. The online guide gives extensive information on the provenance of the collection, the history of the diocese, and the explanation of how to use the collection. Researchers can browse by date or name or can search by keyword. For more information, please contact the Archivist and Curator of Manuscripts.

<img class="aligncenter" src="http://www.archives.nd.edu/mano/0002/00000045.gif" alt="" width="434" height="549" 1719 Feb. 14

Nepuouet, Galpand, notary in the court of Montreuil Bellay and Arpairteur sworn resident at the royal seat of Senechaussee de Saumur and Andre Hullin, notary royal. Rochettes, (France)

A marriage agreement between Perrine Bazille widow of Jean Douet, laborer, mother and guardian of Marie, Perrine, Francoise and Anne Douet her children and those of the deceased on the one side; and on the other side Gille Beaumont, laborer. The parties live at Rochettes, parish of Concourson. Property arrangements were made. (This document was drawn up in France).

GPHR 45/2646: Four Notre Dame Presidents Gathered Together, 1956/1221.

GPHR 45/2646: Four Notre Dame Presidents Gathered Together, 1956/1221.

Tickets and press credentials for the Washington Day Exercises, 1960-1964

Tickets and press credentials for the Washington Day Exercises, 1960-1964 Senator John F. Kennedy receiving the Patriot of the Year Award from Senior Class President George Strake at the Washington Day Exercises, February 1957.

Senator John F. Kennedy receiving the Patriot of the Year Award from Senior Class President George Strake at the Washington Day Exercises, February 1957.

Program cover from the 1965 Washington Day Exercises and Patriot of the Year Award Ceremony. R. Sargent Shirver Jr. received the award this year.

Program cover from the 1965 Washington Day Exercises and Patriot of the Year Award Ceremony. R. Sargent Shirver Jr. received the award this year.

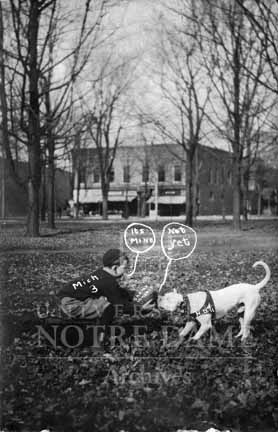

The rivalry heated up in 1909 when Notre Dame went into Ann Arbor with a then 0-8 series record. The Notre Dame victory came as a shock to Michigan fans and would later be the focal point in the debate over which team was the true Champion of the West. Notre Dame went undefeated except for a tie to Marquette and Michigan only lost to Notre Dame. Sports writers around the country debated for months with no clear resolution. The yearbooks from both schools claimed bragging rights to the championship that year.

The rivalry heated up in 1909 when Notre Dame went into Ann Arbor with a then 0-8 series record. The Notre Dame victory came as a shock to Michigan fans and would later be the focal point in the debate over which team was the true Champion of the West. Notre Dame went undefeated except for a tie to Marquette and Michigan only lost to Notre Dame. Sports writers around the country debated for months with no clear resolution. The yearbooks from both schools claimed bragging rights to the championship that year.

[Source:

[Source: