Like many other American universities in the late 1940s, Notre Dame saw an influx of a new type of student: a World War II veteran on a G.I. Bill with a wife and possibly children. Since Notre Dame did not have married student housing at the time and alternate housing in South Bend was scarce, “Vetville” was created to fill this need. Vetville opened in the Fall of 1946, housed 117 families, and occupied areas of Mod Quad along Bulla and Juniper Roads. Each building consisted of three two-bedroom apartments with a kitchen and bathroom and was constructed of “thirty-nine prisoner-of-war barracks [from] a military camps in Weingarten, Missouri” [Schlereth, page 191].

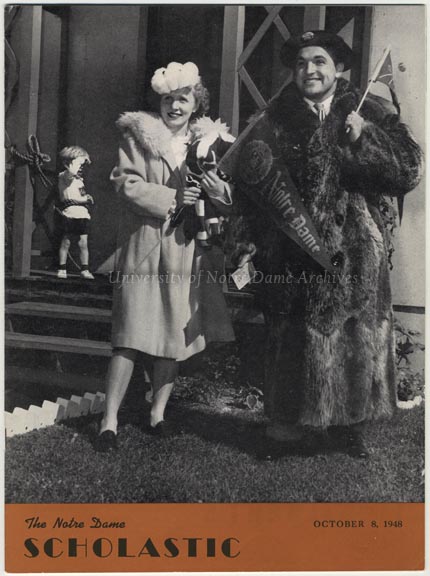

Caption: “With a bow to the Vet Gazette’s Tracey Cummings from whom Scholastic stole the idea for this week’s cover, we present a problem which plagues Diaperville each time the team plays ball in the stadium. Mr. and Mrs. Chuck Perrin and recalcitrant Junior, roped securely to the old homestead, typify the difficulties of going anywhere sans offspring. Junior, never fear, will exact his pound of flesh by an orgy of mural-painting on the living room wall during his parents’ absence.”

Vetville was its own village, with six wards, council representatives, and a mayor “who was charged to negotiate with the University administration for better garbage collection, paved streets, food cooperatives, and playgrounds.” In addition to carrying a full academic course-load, most of the students and many of their wives held down full-time jobs, trying to make ends meet, while also raising a family in tight living quarters [Schlereth, pages 191-192].

The lives of the married students and their families are well documented through the weekly newspaper, which debuted on April 30, 1947, and ran in one form or another through 1962. It announced events, accomplishments, guidance, and other information for the Vetville families.

Notre Dame did not intend the barracks of Vetville to be permanent housing. As the enrollment of veterans with families waned in the late 1950s, plans for new, modern residence halls, library, and chapel were laid out in the early 1960s. The Vetville buildings and Navy Drill hall were demolished by 1962 to make room for the new construction. However, Notre Dame also recognized the need for married students housing and the Cripe Street Apartments for married students was completed in 1962 as Vetville vanished.

On June 11, 1966, former Vetville Chaplain Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, dedicated a plaque on the hill just north of the Memorial Library (now called Hesburgh Library) to the families who spent their years at Notre Dame in Vetville. It reads, “This area was the site of ‘Vetville,’ married student housing 1945-1962. Many were the trials — Thanks to the Holy Family for the many blessings needed to persevere.”

Sources:

PNDP 10-Ve-01

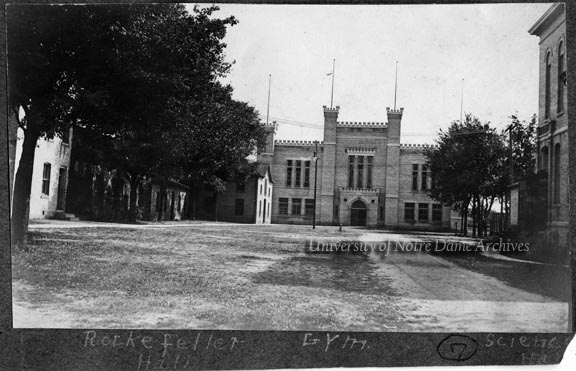

PNDP 83-Nd-3s

Scholastic

The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History and Campus by Thomas Schlereth (1976)

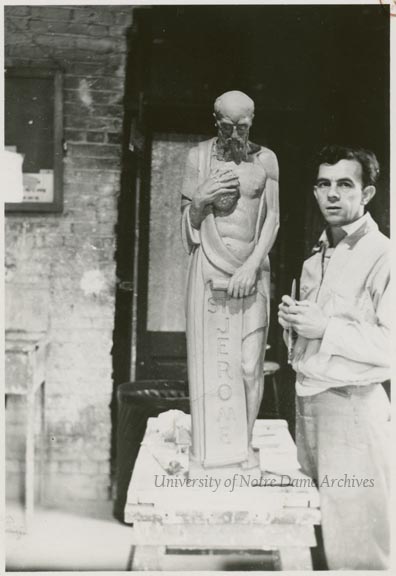

GPHR 45/4144

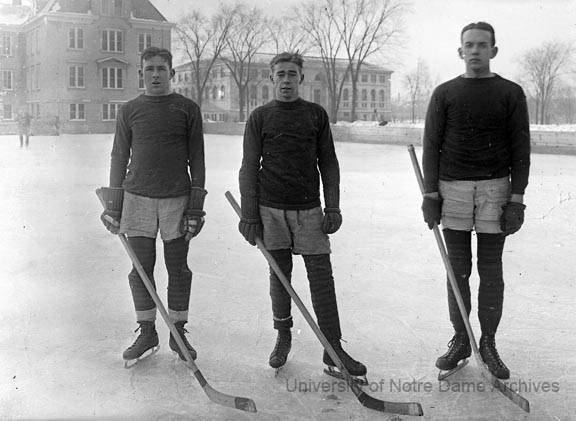

GPHR 45/2382