The first Senior Bar building has an unlikely history. The house was built in 1916 as a private residence and was known as the McNamara House. In 1951 the house was converted into a home for men in formation to the Brothers of the Congregation of Holy Cross and renamed André House after now Saint Brother André Bessette, CSC.

André House facing Eddy Street, March 1951.

André House facing Eddy Street, March 1951.

This space is now occupied by the current Legends Restaurant

André House served as a home for the brothers for about a decade. It was then used as a Faculty Club in the 1960s. At this same time, the Senior Class would designate a local, off-campus watering-hole as “Senior Bar.” The location changed yearly and students worked with local establishments to have a private club for Notre Dame seniors and their dates over the age of 21 who purchased membership.

The opportunity for students to move Senior Bar to campus came when the University Club opened in 1968 along Notre Dame Avenue (razed in 2008) and André House was once again vacant. In January 1969, the Alumni Association took over the old house and opened Alumni Club. Of-age seniors could gain membership and “senior class managers handled the day-to-day operations of the club” [Scholastic, 12/05/1975, page 18]. Alumni Club could accommodate several hundred people and offered bars, pool tables, and dancing areas.

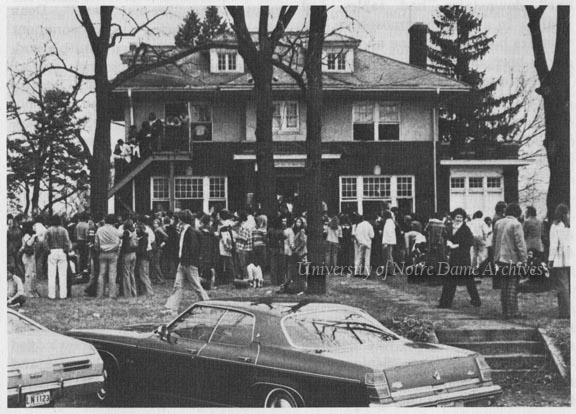

Students outside of Alumni-Senior Club, c1970s

Students outside of Alumni-Senior Club, c1970s

Students dominated Alumni Club and the Alumni Association backed out of the venture in 1974. After much negotiation, the club moved under the auspices of the Office of Student Affairs and changed the name to Alumni-Senior Club. Ever since 1969, the popularity and financial stability of Alumni-Senior Club ebbed and waned. The 1916 building became cost prohibitive to physically maintain. In 1982, a new Senior Bar was built on the same location as the old house. The new building, designed with input from students, offered three times as much space as the old building. It included three bars, two dance floors, and a game room with pool tables and video games.

Senior Bar (Alumni-Senior Club) exterior, March 1999

Senior Bar (Alumni-Senior Club) exterior, March 1999

In 2003, Senior Bar was transformed into Legends Restaurant and the lifetime memberships held by alumni were no longer valid. One side of Legends houses a restaurant open to the public. The club side is generally used for private parties or student-only events.

Sources:

Scholastic

PNDP 10-An

PNDP 30-Al-02

GPHR 45/1366

GSCO 3/93

Ghoul John Morgan playing a piano at Carroll Hall’s Haunted House, 1988

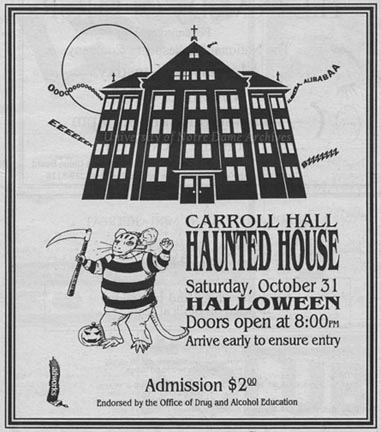

Ghoul John Morgan playing a piano at Carroll Hall’s Haunted House, 1988 Advertisement for Carroll Hall’s Haunted House in the Observer, 1992/1029

Advertisement for Carroll Hall’s Haunted House in the Observer, 1992/1029