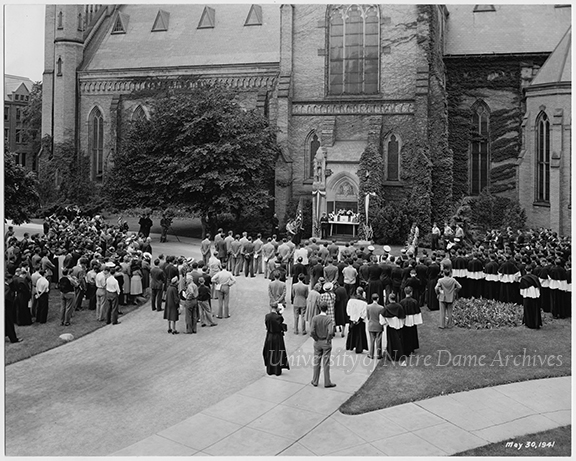

On Memorial Day, May 30, 1924, University President Rev. Matthew Walsh dedicated the World War I Memorial at Notre Dame before saying a military field mass in front of it. The memorial is an addition to the east transept of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart designed by Notre Dame architects Francis Kervick and Vincent Fagan. The professors also designed Cushing Hall of Engineering, Howard Hall, Lyons Hall, Morrissey Hall, and South Dining Hall.

The cry for a memorial for Notre Dame’s contributions to the Great War began shortly after armistice in 1919. The memorial initially was going to have inscribe all 2500 Notre Dame active students, alumni, and faculty members who served. In that number were two future University Presidents who served as chaplains during WWI – Rev. Matthew Walsh and Rev. Charles O’Donnell. In the end, the tablets only list the names of the 56 who sacrificed their lives in the war.

The Notre Dame Service Club worked diligently to raise funds for the memorial through dances, Glee Club concerts, and general petitions in Scholastic. Notre Dame formed a post of Veterans of Foreign Wars in January 1922, which then took up the efforts. The VFW disbanded in 1923, as there would be few veteran students left on campus to keep the post going. They had hoped to have the memorial complete by the end of their run, but it would still be another year before it would be finished.

In January 1923, a special committee of Notre Dame’s VFW post approved Vincent Fagan’s design for the memorial to be a new side-entrance to the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, the idea favored by University President Walsh (see sketch above). Scholastic noted that “[t]he design is beautiful and appropriate and will add charm to the campus as well as ‘hold the mind to moments of regret'” (Scholastic, March 24, 1923, page 677).

The real purpose of a memorial, from the Catholic point of view, is to inspire a prayer for those we desire to remember. It is very proper that this memorial should be a part of the Church of Notre Dame.

No one who knows Notre Dame need be told of the spirit of loyalty and faith that has animated this university from its beginning. We should imitate our dead in that they have shown us the lesson of patriotism. If only the people of America would follow their example there would be no discrimination because of race or creed. When Washington said that religion and morality are the basis of patriotism he gave us the definition to every patriotic move at Notre Dame.

It is to the boys of the World War and to the men of the Civil War that this memorial is dedicated. Let us ask God that this memorial will not only be beauty in stone, but also a reminder to pray for the men to whom it is dedicated.

(Notre Dame Daily, May 21, 1924, page 1)

For many years, the memorial door was the natural place to hold mass on Memorial Day and other military occasions. With the changes made to altar placement with Vatican II and the academic year ending well before Memorial Day, this tradition has gone by the wayside. The memorial remains an important corner of campus and the “God, Country, Notre Dame” inscription is often quoted today.

Mass at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart World War I Memorial Door, 1925.

Mass at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart World War I Memorial Door, 1925.

Sources:

Scholastic

Notre Dame Daily

GNDL 28/29

GHOP 1/08

GNDS 5/11

GDIS 29/02

GPUB 6/39

Scholastic, December 28, 1867

Scholastic, December 28, 1867

Thanksgiving Day Menu for the Oliver Hotel, South Bend, Indiana, 11/29/1906

Thanksgiving Day Menu for the Oliver Hotel, South Bend, Indiana, 11/29/1906

Thanksgiving Day Menu for the Congress Hotel Company, Chicago, banquet after the

Thanksgiving Day Menu for the Congress Hotel Company, Chicago, banquet after the

Notre Dame Dining Hall Thanksgiving Day Menu, 11/23/1939

Notre Dame Dining Hall Thanksgiving Day Menu, 11/23/1939

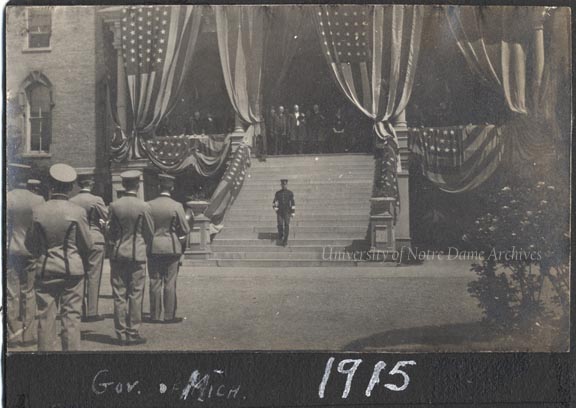

GNDS 2/11: Main Building decorated with American flags for the visit of the Governor of Michigan, 1915. In the foreground are SATC students in military uniforms.

GNDS 2/11: Main Building decorated with American flags for the visit of the Governor of Michigan, 1915. In the foreground are SATC students in military uniforms.

CEDW 16/11 (Calendared XI-2-m): Easter postcard that reads “Holy Easter, time of blessing, May we each rejoice and sing, Giving praises, heartfelt praises, To our risen Easter King.” This postcard was sent to

CEDW 16/11 (Calendared XI-2-m): Easter postcard that reads “Holy Easter, time of blessing, May we each rejoice and sing, Giving praises, heartfelt praises, To our risen Easter King.” This postcard was sent to

band in front of the college and in the afternoon Randolph and myself and four other boys went asked one of the Brothers to take us up in the steeple [of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart] to see the Bells which he did immediately so when we got up their three or four of the boys tapped to see how loud it would sound the bell weighs seventeen thousand pounds and, it takes four men to wring it and after he’d played two or three tones by chains. And still St. Patrick was not over yet in the evening they all assembled in the Rotunda of hear some of the boys speak in which George Clark delivered a very fine piece of poetry he is the best speaker of the students of Notre Dame and is a resident of Cairo, Illinois. This is all for the present, so when you receive this letter I suppose you will answer it with more latitude than the last, for I suppose that time are not so hard. Best regards,

band in front of the college and in the afternoon Randolph and myself and four other boys went asked one of the Brothers to take us up in the steeple [of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart] to see the Bells which he did immediately so when we got up their three or four of the boys tapped to see how loud it would sound the bell weighs seventeen thousand pounds and, it takes four men to wring it and after he’d played two or three tones by chains. And still St. Patrick was not over yet in the evening they all assembled in the Rotunda of hear some of the boys speak in which George Clark delivered a very fine piece of poetry he is the best speaker of the students of Notre Dame and is a resident of Cairo, Illinois. This is all for the present, so when you receive this letter I suppose you will answer it with more latitude than the last, for I suppose that time are not so hard. Best regards,