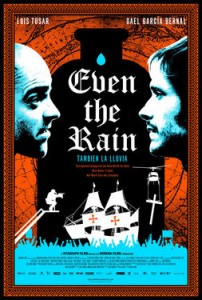

Movies that are about making movies aren’t that good normally. They are often distracting and self-absorbed (Charlie Kauffman’s “Adaptation,” for all its creativity, stands out here). So when a movie comes along and demonstrates the real potential of using this narrative style, it deserves special recognition. “También la lluvia” (“Even the Rain”), directed by Icíar Bollaín, is such a movie. But it is so much more.

The movie revolves around a couple of Spanish filmmakers, Costa and Sebastián, played by Luis Tosar and Gael García Bernal, respectively. They arrive with their film crew to Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 2000 during a moment of great social upheaval over the privatization of water. The poor, mostly indigenous population of Cochabamba struggle enough to survive by living on less than $2/day. When a company arrives under government permission to restrict their water access for the purpose of making a profit from them, it creates dramatic backdrop that emerges to the forefront as the film progresses.

The Spaniards who arrive are not making any ordinary film, but one about Columbus, the conquest of the Americas, and the first Dominicans who opposed the Crown’s policy. This is why the movie works so effectively as a film within a film. It juxtaposes a real historical crisis in Bolivia’s recent history with real historical characters (i.e., Bartolomé de las Casas and Antonio de Montesinos) that provide a continuous prophetic critique in the name of justice and holiness in the film crew and the movie viewer.

One of the local indigenous chosen by Costa and Sebastián to star in the movie is Daniel (Juan Carlos Aduviri). Chosen to play the great Taíno hero Hatuey because of his passion for justice and leadership, Daniel is also spearheading the local protest against water privatization. This allows the dramatic tension of the social context to become personal for Costa and the film crew.

The film works on so many levels. The cinematography is intimate and beautiful. The premise of a movie within a movie is not a source of distraction because when the scenes of the sixteenth century are being shown in the film, the camera and directors disappear allowing for a more seamless layering of time periods as the movie draws to its heart-pounding conclusion. The music is deeply soothing and yet tense when it needs to be due to its usage of string instruments. All of this creates a wonderful tapestry for a film that is really about solidarity and the cross in an age of deep regret, loneliness, and waywardness.

“Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me.” (Mark 8:34) In the opening moments of the movie, a giant wooden cross is brought by helicopter to the set of the film. The viewer knows that this is not mere coincidence as the decision to take up the cross weighs on the conscience of the film crew more and more. The historical characters of Las Casas, Columbus, and Montesinos figure richly into the narrative. We hear the speech that Montesinos gave in Hispaniola in 1511 (during Advent December, not March, as the film incorrectly suggests). We also hear the speech of Hatuey given before his heroic death.

What makes this movie so exciting, at least for someone who studies or cares about this moment in early modern history, is that it presents the conflicted interpretations of contemporary Spaniards. In the actor who plays Christopher Columbus (a very humorous and brilliant performance by Karra Elejalde), we get a sense of the pride and doubt regarding the “bright side” of the New World conquest. There is an incredible dinner scene with excellent dialogue that provides an example of what I am talking about. The actors are gathered around talking about the movie and the social crisis. Antón or Columbus (Elejalde’s character) challenges the actor who plays Las Casas to defend his alter-ego. Antón, not unlike the clamorous historical Dominican counterpart, plays the role of prophet in the contemporary setting. But whereas the criticism of Montesinos arose from the Gospel imperative to love and a desire for God’s justice, Antón’s critique is rooted in cynicism and spiritual unrest. He asks: was Las Casas really just another face of empire as one author has recently suggested? Did he not, after all, defend the African slave trade as an alternative to Indian slavery? These are difficult questions that need to be treated carefully. Unfortunately, the film does not fully acknowledge that Las Casas deeply regretted thinking this way and why he did. Rolena Adorno has written authoritatively about the subject in The Polemics of Possession in Spanish American Narrative (see pp. 66-68). The challenging question that the film raises for Spaniards and everyone else, however, is: how much are they willing to defend by words the personality of someone like Las Casas when their lives and example do not?

Even though we can all sympathize with the voices of cynics and skeptics in our spiritually impoverished age, are we left with this as our only path? That the film provides an answer to this in the negative is truly its greatest contribution as both a Spanish and Latin American film for the rest of the world. Without giving away too much, I cite moments of dialogue that poetically capture the significance of water and rain in the movie that points us toward the way of justice, love, and truth. Costa at one point asks Antón why he drinks so much liquor. Antón responds that is it is because he is very, very, very thirsty.

The translated movie title, “Even the Rain,” is, in my interpretation, not merely a reference to the material dilemma over water, but also a spiritual reference to Jesus’ teaching that God allows the rain to fall on the just and unjust alike. The two characters in the movie that demonstrate this juxtaposition of righteousness and injustice–clearly evident early on in the movie–are Daniel and Costa. The beautiful fact that the movie points a way out of injustice by promoting solidarity and the call to holiness is suggested when Daniel says in defense of his social movement against the selfish Costa interested in finishing the movie, “Without water, you would understand.”

This last statement, in my opinion, captured the movie’s deep insight into the need, sometimes, for revolution as a matter of self-defense and survival. After all, this is what made Las Casas and his Salmantine counterparts so problematic to the Spanish Crown. They argued incessantly: the Indians have a right of self-defense against the aggressive Spaniards. When push comes to shove, and the context ripe, this is demanded especially of Christians who wish to take up the cross and deny themselves. But there is always a choice: martyrdom or just heroism. I think it would be a travesty to elide the fact that the cross and self-sacrifice appear in both instances even though there are important differences. The movie shows how this is so through solidarity. I heartily recommend it and the fact that it was not finally nominated for best foreign film at the Oscar’s gives me little hope, as always, for Hollywood.