Pregnancy is viewed as a normal process of life, a cycle that is repeated so frequently that the risks are often forgotten. However, millions of pregnant women die before, during, or after birth each year, largely due to preventable causes. Lack of access to health care (an obstacle faced by many women living in rural areas) is a huge risk factor for maternal and infant mortality/poor birth outcomes. Furthermore, the intersection of little to no health care and impacts of climate change poses an even greater risk for rural women. Surmounting evidence shows that the negative effects of climate change compound on pregnant women in rural areas to a higher degree than women in nonrural areas. As the earth continues to warm, healthcare initiatives must be put in place to protect rural pregnant women and prevent poor birth outcomes.

Living on the Moon

The shocking distance from health providers experienced by some communities can be perfectly encapsulated by Stan Brock, the creator of Remote Area Medical (a program that provides free pop-up clinics to rural communities). When describing a trip to a rural area of the Amazon, locals told him that the nearest doctor was 26 days away by foot. After relaying the story to astronaut Ed Mitchell, Brock was told that astronauts on the moon were a mere 3 days away from the nearest doctor.2 Brock’s grave revelation that people living in remote areas of the world are basically living on the moon has stark implications for pregnant women.

“People in the rural Amazon and rural America basically live on the moon.”

Stan Brock from Remote Area Medical2

Pregnant women living in rural areas with little to no access to healthcare have heightened vulnerability to several factors that climate change also influences, such as environmental health and housing/food security. The limited access to health providers increases risk of poor birth outcomes when complications from these factors occur; in fact, over half of rural American women live at least 30 minutes away from a hospital with a labor and delivery unit.5 It is also common for rural women to attend prenatal appointments much later in their pregnancies than nonrural women.5 Furthermore, environmental hazards from industries commonly found in rural areas (such as agriculture, logging, and mining), unsafe housing that lacks temperature control and other necessities, and limited access to fresh and affordable food pose existing threats to the health of pregnant rural women.5 These social determinants of rural health compound the effects of climate change, creating a dangerous environment for rural women to go through their pregnancies.

Climate Change and Pregnancy Outcomes

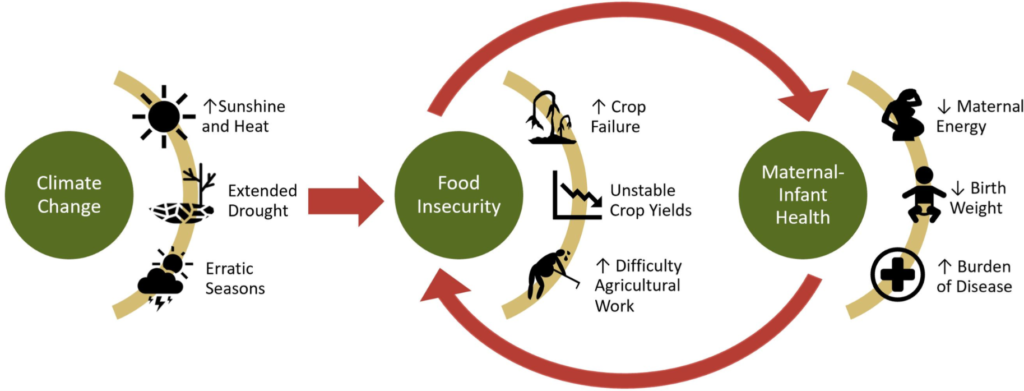

As the effects of climate change become increasingly drastic, it is important that healthcare workers are prepared to combat the negative consequences on pregnant women’s health. As global temperature hikes increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as droughts, food insecurity subsequently increases. Such weather conditions also make homes without temperature control unsafe to live in, which can lead to negative birth outcomes, increased morbidity, and forced migration. Tropical developing countries, along with any areas with high poverty rates, poor healthcare systems, or little to no healthcare access will be hit the hardest by these effects.3 Many rural communities fall into all of these high risk areas, meaning increased prenatal care to rural women is integral.

As the most vulnerable members of society, pregnant women, fetuses, and newborns are prone to suffering from the effects of food/housing insecurity and high ambient temperatures. During pregnancy, energy demand increases by 20%.3 This means that more food is required for all of a pregnant woman’s bodily functions to operate at full capacity, but food insecurity means that food is not a reliable source in equal quantities throughout the pregnancy. Underweight women are more likely to give birth to underweight or intrauterine growth restricted babies, which inherently places newborns in a vulnerable position.3 Additionally, food and water insecurity leads to mass migration. With an estimated several hundred million climate refugees by 2050, prenatal care will be virtually impossible for displaced women.3 Throughout the upcoming decades, the lives and health of pregnant women and newborns are in imminent danger.

Ugandan Case Study

“During the dry season, it’s suffering. If you don’t save what [food] you had during the rainy season, then in the dry season you find you have nothing when you are pregnant.”

Women from rural communities in Kanungu District of Uganda1

The damage to the health of pregnant women living in tropical, rural areas is exemplified by a case study conducted in the rural Kanungu District in Uganda. This area is already threatened by food insecurity due to droughts and other weather that harm the region’s agriculture, particularly in the dry season. In a series of interviews conducted with adult women of all ages, it was noted that the rainy season is the best because “every crop grows” and that the insecurity has reached a point where food grown in the rainy season must be saved for the dry season to avoid starvation.1 The women reported many negative symptoms during pregnancy, including “nausea”, “general malaise”, “dizziness”, “shivering”, and “weakness”, in addition to a recent increase in babies that are “weak”, “small”, and “having more sickness”.1 They noted that this was due to mothers not having enough to eat anymore due to droughts. Another observation indicated that babies born in the rainy season are typically stronger due to an increase in food availability towards the end of pregnancy. Since food variability late in pregnancy becomes increasingly detrimental to the health of the baby, some mothers expressed interest in trying to plan pregnancies around rainy and dry seasons, although this often isn’t possible due to family planning challenges.1 The health observations by these mothers make it evident that climate change is already affecting rural regions negatively and that it will only continue to do so as global temperatures increase.

Implications

Although millions of rural women are at risk of increasingly dangerous pregnancies in the upcoming decades, there isn’t a lot of research documenting the physiological reasons negative birth outcomes due to various climate change effects occur.4 How can public health officials be prepared to face a crisis that they aren’t armed to fight? Until research investigating the physiological effects of factors such as heat exposure at different gestational periods, chronic heat exposure, and heat acting in tandem with environmental pollutants becomes available, increasing the amount of prenatal care to rural women is the best solution.4 Hopefully, awareness of the risks that rural pregnant women face in the upcoming decades will become more widespread before a major public health crisis occurs. In our ever changing world, we cannot let rural women and their babies fall through the cracks.

References

1Bryson, J., Patterson, K., Berrang-Ford, L., Lwasa, S., Namanya, D. B., Twesigomwe, S., Kesande, C., Ford, J. D., & Harper, S. L. (2021). Seasonality, climate change, and food security during pregnancy among indigenous and non-indigenous women in rural Uganda: Implications for maternal-infant health. PloS One, 16(3), e0247198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247198

2 Remote Area Medical. Directed by Farihah Zaman and Jeff Reichert, Candescent Films, 2013.

3 Rylander, C., Øyvind Odland, J., & Manning Sandanger, T. (2013). Climate change and the potential effects on maternal and pregnancy outcomes: an assessment of the most vulnerable – the mother, fetus, and newborn child. Global Health Action, 6(1), 19538–19539. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.19538

4 Samuels, L., Nakstad, B., Roos, N., Bonell, A., Chersich, M., Havenith, G., Luchters, S., Day, L.-T., Hirst, J. E., Singh, T., Elliott-Sale, K., Hetem, R., Part, C., Sawry, S., Le Roux, J., & Kovats, S. (2022). Physiological mechanisms of the impact of heat during pregnancy and the clinical implications: review of the evidence from an expert group meeting. International Journal of Biometeorology, 66(8), 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-022-02301-6

5 “Social Determinants of Health for Rural People.” Social Determinants of Health for Rural People Overview, Rural Health Information Hub, 6 June 2022, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/social-determinants-of-health.