For college students struggling with mental health, the weight of stigma and shame can feel heavier than the textbooks in their backpacks. Mental health conditions are among the most prevalent health issues affecting college students today. According to the American College Health Association, 63% of college students experienced overwhelming anxiety in the past year, while 40% reported symptoms of depression (Greenfield, B., & Gracey, E. 2010). However, despite the prevalence of these conditions, mental health stigma remains a major issue on college campuses. The stigmatization of mental illness can cause students to feel ashamed and embarrassed about their conditions, leading them to avoid seeking help and exacerbating feelings of isolation and social exclusion (Eisenberg, et al 2012).

Understanding the intersections of mental health and other types of marginalization is critical for effectively addressing mental health stigma on college campuses. This necessitates a consideration of how other kinds of oppression, such as ableism, racism, sexism, and homophobia, compound mental health stigma, and how these intersecting identities influence students’ experiences with mental health stigma.

In addition, decreasing mental health stigma involves a multi-pronged approach that targets the root causes of stigma, including as ignorance, fear, and misinformation, as well as the institutional and structural barriers that impede students from gaining access to the necessary services and assistance. By examining structural and institutional barriers to accessing care, promoting inclusive and affirming attitudes toward mental health, and addressing the intersectionality of mental health stigma and other forms of marginalization, we can create a higher education system that is more equitable and supportive for all students.

Factors Contributing to Mental Health Stigma in College Campuses

The stigmatization of mental illness in college campuses is deeply rooted in personal and social meanings of mental illness.

“The social organization of illness, including its meanings and symptoms, determines the cultural response to illness and the quality of care that patients receive”

Kleinman Arthur, Illness Narratives, 2017.

The preceding statement by Kleinman reaffirms that the way in which society views mental illness can affect the treatment and assistance provided to those with mental health disorders (Kleinman 2017). The stigmatization of mental illness prevents individuals from seeking care and discussing their experiences for fear of being judged by others. As detailed in Kleinman’s Ilness Narratives, broader societal attitudes and ideas about mental health shape the social meanings of mental illness. Contributing to the stigma around mental illness are media representations of mental disease, misconceptions of people with mental health disorders, and a general lack of knowledge and awareness. In Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha examines how cultural and societal notions about disability intersect with mental health stigma (Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018). She adds that people with disabilities may be perceived as “unwanted” or “broken,” resulting in stigma and prejudice. In addition, mental health issues may be stigmatized due to cultural views about “normalcy” and able-bodiedness, which can result in feelings of shame and humiliation (Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018).

Furthermore, the interconnectedness of disability and mental health further complicates the problem of mental health stigma on college campuses. According to Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Crip Emotional Intelligence, individuals with impairments are frequently subjected to stigma and discrimination, which may increase their risk of developing mental health issues (Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. 2018). In addition, the lack of accessibility and inclusivity on many college campuses can create further barriers for students with disabilities seeking mental health support.

“The disability community knows firsthand what it’s like to be told that our pain doesn’t matter, that our bodies are wrong, and that we don’t belong”

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Crip Emotional Intelligence

Specific examples of mental health stigma on college campuses illustrate these personal and social connotations of mental illness, as well as the intertwining of disability and mental health (Piepzna-Samarasinha, L 2018). For instance, individuals with mental health disorders are frequently described using negative language and stereotypes, reinforcing detrimental attitudes and beliefs. In addition, kids with mental health disorders may be excluded from social gatherings or treated harshly in the classroom, leading to feelings of isolation and perpetuating the stigma associated with mental illness. On college campuses, the stigma surrounding mental health is pervasive and well-documented (Lu, et al. 2019). Students with mental health disorders may encounter discrimination and negative attitudes from their peers, professors, and even healthcare professionals. Additionally, these students may have difficulty gaining access to necessary mental health resources on campus due to restricted availability, lengthy wait periods, or substandard care. The stigma associated with mental health may also discourage students from seeking assistance or admitting their condition, resulting in feelings of isolation and social exclusion (Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. 2018).

Impacts of Mental Health Stigma on Students and Campus Culture

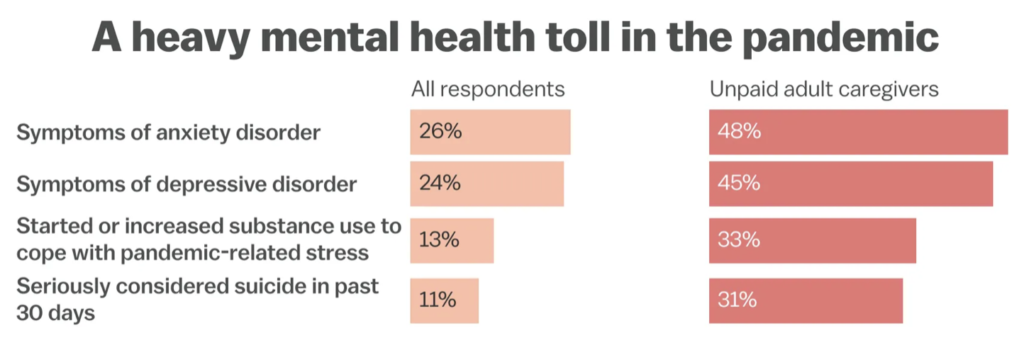

The impact of mental health stigma on students and campus culture is profound and cannot be overstated. Daniel Eisenberg, of Mental Health on College Campuses: A Review, discovered that stigma and discrimination against students with mental health disorders are pervasive on college campuses, with many students avoiding assistance out of fear of receiving negative labelsand social rejection (Eisenberg et al., 2012). The American College Health Association (2019) reported that 63% of college students experienced overwhelming anxiety in the past year, while 40% reported symptoms of depression. However, only 20% of students with mental health conditions sought help from a mental health professional (Eisenberg et al., 2012). This can lead to detrimental consequences for students, including lower academic performance, decreased quality of life, and higher rates of substance abuse and suicide (American College Health Association, 2019).

The stigma associated with mental health also has a significant effect

on campus culture. Corrigan and Watson, of The Paradox of Self-stigma and Mental Illness, discovered that stigma can create a hostile and unsupportive atmosphere for students with mental health disorders, resulting in social isolation and limited access to resources and support. This can perpetuate the stigma and prejudice cycle,establishing a culture of neglect and apathy toward mental health. (Corrigan, 2004). Furthermore, the lack of money and resources for mental health services, as well as the dearth of skilled mental health practitioners on college campuses, exacerbates the impact of stigma and leaves many students without the care they require. (Eisenberg et al., 2012).

The impact of mental health stigma on students with mental health conditions is also profound. Linton, of The Ableism of Disability Studies, argues that mental health stigma can lead to a form of “internalized ableism,” where students with mental health conditions begin to internalize the negative attitudes and stereotypes associated with their condition and view themselves as inferior or inadequate (Linton, 2018). This can lead to self-doubt, low self-esteem, and a reluctance to seek help or disclose their condition to others (Linton, 2018). Furthermore, students with intersecting marginalized identities, such as those who identify as LGBTQ+ or have disabilities, are at an even higher risk for mental health stigma and its effects, exacerbating the impact of stigma on their mental health and overall well-being (Kaufman et al., 2018).

A comprehensive and evidence-based strategy is required to mitigate the effects of mental health stigma on students and campus culture. Vogel of Mental Health Stigma on Campus: A Review of Literature and Implications for Practice, argue that interventions that focus on developing mental health literacy, encouraging inclusive and affirming attitudes toward mental health, and strengthening access to resources and support can aid in reducing stigma and improving mental health outcomes for students (Vogel et al., 2007). In addition, policies that prioritize the recruitment and retention of diverse mental health professionals, as well as the provision of proper financing and resources for mental health services, can assist in addressing the shortage of resources and promoting a more equitable and inclusive campus culture. (American College Health Association, 2019).

The impact of mental health stigma on campus culture is also significant (Vogel et al 2007). Stigma can create a hostile and unsupportive environment for students with mental health conditions, leading to social isolation and a lack of access to resources and support (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). This can further perpetuate the cycle of stigma and discrimination, creating a culture of neglect and apathy towards mental health (Corrigan, 2004). Furthermore, the lack of resources and financial support for mental health services, as well as a shortage of skilled mental health practitioners on college campuses, exacerbates the impact of stigma and leaves many students without the care they require. (Eisenberg et al., 2012).

Potential Solutions to Address Mental Health Stigma in College Campuses

Mental health stigma is a pressing issue on college campuses, as it can prevent students from seeking help and exacerbate feelings of isolation and social exclusion (Greenfield, B., & Gracey, E. 2010). According to a survey conducted by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), 64% of college students with mental health conditions report that stigma has made it difficult for them to succeed academically, and 50% report that stigma has prevented them from seeking help (Nelson, 2011). Additionally, a study by Eisenberg and colleagues (2013) found that only 11% of college students with mental health conditions receive treatment, with stigma being the most common barrier to seeking help (Eisenberg et al., 2012).

Several potential solutions have been proposed in the literature, including destigmatizing language and practices, increasing awareness and education, and involving students with mental health conditions in decision-making. According to Greenfield and Gracefield, of Disability Awareness: A Course for College Students. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, disability awareness courses are one technique to enhance awareness and education (Greenfield, B., & Gracey, E. 2010). These courses allow learners to comprehend the experiences of people with disabilities, specifically those with mental health disorders. In addition, Lu and Feeley of Reducing Mental Health Stigma on College Campuses: Targeting External and Internal Sources of Stigma, argue that external causes of stigma, such as negative media portrayals, can be countered by media campaigns that challenge stigmatizing mental health representations (Lu & Feeley, 2018). Moreover, internal origins of stigma, such as self-stigma and shame, can be addressed through therapy procedures that emphasize the development of self-esteem and self-acceptance (Lu & Feeley, 2018).

However, these prospective solutions are not devoid of obstacles and constraints. Greenfield and Gracey, for instance, remark that disability awareness classes are not yet extensively implemented on college campuses, and there is a need for additional research to evaluate their efficacy (Greenfield, B., & Gracey, E. 2010). In addition, Lu and Feeley (2018) admit that media campaigns can be costly and difficult to continue, and that they may not necessarily alter deeply rooted cultural attitudes around mental health (Reczek et al (2016). Similarly, therapeutic interventions may not be available to all kids, especially those from marginalized backgrounds who may experience significant challenges to care access (Lu & Feeley, 2018).

Despite these challenges, college campuses have begun implementing effective programs and initiatives to combat mental health stigma. For instance, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work, explores the role of “crip emotional intelligence” and “sick and crazy healer” in creating supportive and inclusive spaces for people with disabilities, including those with mental health conditions (Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. 2018). Similarly, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) has created initiatives like as Ending the Silence and NAMI on Campus to improve awareness, decrease stigma, and give resources and support for students with mental health disorders (Eisenberg, et al 2009).

Going Beyond the Classroom

As a current undergraduate student pursuing pre-health and global affairs at the University of Notre Dame, I am acutely aware of the critical importance of mental health in the college setting. College represents a pivotal time for young adults as they navigate new experiences, opportunities, and challenges that can profoundly shape their personal and professional trajectory. However, mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress can significantly impact a student’s academic, personal, and social life, making it difficult for students such as myself, to thrive in this dynamic and demanding environment.

The stigma surrounding mental health further exacerbates these challenges, creating significant barriers for students to access care and support, hindering their ability to manage and overcome their conditions effectively. Moreover, given that college graduates are often future leaders and contributors to the building of a more equitable and just society, decreasing mental health stigma on college campuses can have far-reaching effects on society as a whole. By increasing awareness, reducing stigma, and improving access to mental health services and assistance, we can foster a campus environment that is healthier, more resilient, and more conducive to the growth and development of all students.

References

- Crawford, R. (2006). Health as a meaningful social practice. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 10(4), 401-420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459306067310

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(1), 35-53. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35

- Corrigan, P. W. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614-625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. B. (2012). Mental health and academic success in college. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 12(1), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1515/1935-1682.3530

- Linton, S. (1998). The ableism of disability studies. Disability & Society, 13(5), 665-666. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599826619

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. (2018). Crip emotional intelligence. In Care work: Dreaming disability justice (pp. 23-30). Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Hackler, A. H. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.40

- Vogel, D. L., Bitman, R. L., Hammer, J. H., & Wade, N. G. (2013). Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 311-316. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032400

- Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., & Larson, L. M. (2007). Avoidance of counseling: Psychological factors that inhibit seeking help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(3), 410-422. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2007.tb00601.x

- Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., Wei, M., & Boysen, G. A. (2005). The role of outcome expectations and attitudes on decisions to seek professional help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 459-470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.459

- “Mental Health on College Campuses: A Review” by Eisenberg, Golberstein, and Hunt

- “Mental Health Stigma on Campus: A Review of Literature and Implications for Practice” by Vogel et al.

- “The Stigma and Shame of Illness” from Care Work by Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha