Here is another article that concerns infrastructure and entrepreneurship: http://theconversation.com/entrepreneurial-ecosystems-and-the-role-of-regulation-and-infrastructure-37030

Entrepreneurial ecosystems and the role of regulation and infrastructure

This is the second article on the topic of entrepreneurial ecosystems that build on a series of white papers developed by the Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand Ltd (SEAANZ). The first was published here in “The Conversation” in December 2014 and addressed the issues of what an entrepreneurial ecosystem is, and what role government policy can play in helping to foster their emergence and growth.

He we look at the second White Paper, which focuses on the role of regulation, infrastructure and financing. However, in this article I will examine the first two of these issues and devote a later article to financing.

The motivation for this work was the G20 Summit hosted by Australia last year. In particular the special G20 SME conference that was held at the Victorian Parliament House on 20 June 2014. That meeting was convened by the Australian Minister for Small Business Bruce Billson; and organised by the Australian Treasury, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the ANZ Bank, Australian Bankers’ Association and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The role of regulation in entrepreneurial ecosystems

As explained in the first article in this series, an entrepreneurial ecosystem is a conceptualisation of an environment in which the right combinations of elements help to foster economic growth through enterprise and innovation. One of these elements is the regulatory framework in which this entrepreneurial activity is able to take place.

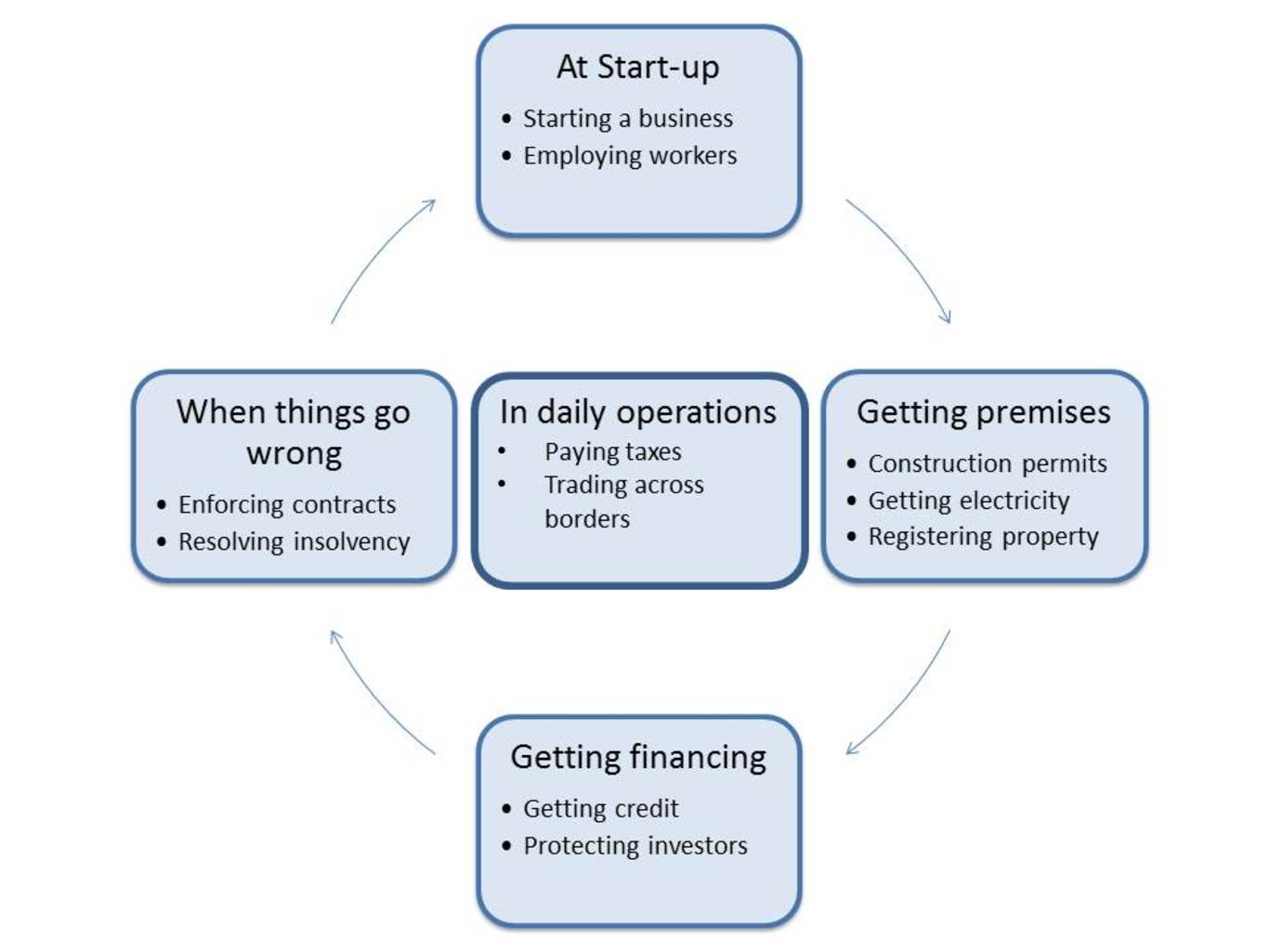

The following diagram illustrates the main regulatory issues that impact on a business throughout its lifecycle. It commences with how easy it is to start-up a new business venture and also how easily the new owners can employ workers. Other key issues relate to the compliance costs of securing premises and having all the necessary utilities and licences secured.

Regulations impacting the business throughout its lifecycle. World Bank (2013)

In many cases local, state and federal government regulations can impact here. The other major issues relate to getting financing, paying taxes and other fees and charges, plus how well the legal system protects small business owners and shareholders, and deals with insolvency.

Government regulation encompasses many things but the World Economic Forum (WEF) has suggested that there are at least three key issues likely to impact on an entrepreneurial ecosystem. These are the ease of doing business, promoting “business friendly” legislation and policies and taxation policy, particularly for small to medium enterprises (SMEs).

Ease of doing business

The first of these issues – “ease of doing business” – is related to what is popularly termed “red tape”, or the amount of compliance costs and bureaucratic encumbrances placed on businesses. A useful global guide to this is the World Bank’s “Doing Business” study that compares 189 nations against a set of measures of how easy or hard it is to do business there.

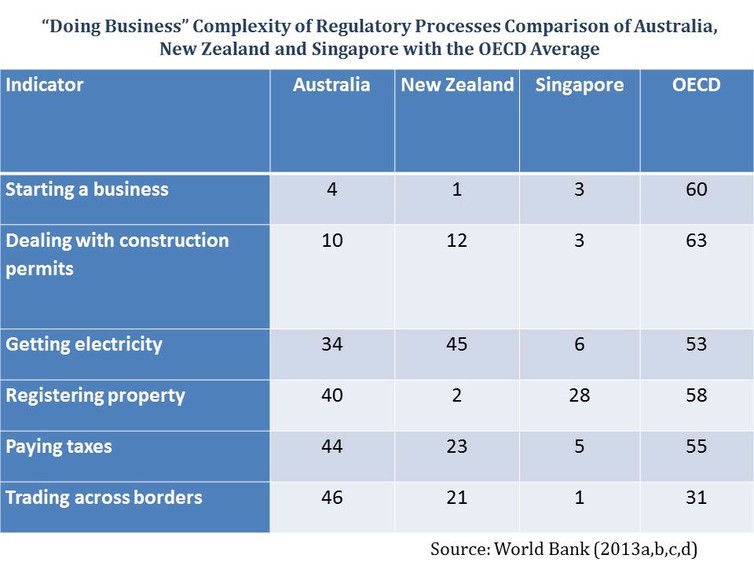

Some of the key criteria used are the ease of starting up a new business, securing construction permits, registering property, getting electricity connected, paying taxes and trading across borders. At a global level New Zealand is the easiest country in the world in which to start-up a new business, ranking first out of 189 nations. Australia, by comparison was ranked 4th in the world with Singapore just ahead in 3rd place.

As shown in the diagram below, Australia and New Zealand rank quite well in comparison with the OECD average across most indicators of ease of doing business. However, they are generally well behind Singapore, which in 2014 was ranked number 1 out of all countries surveyed by the World Bank.

Doing Business – Complexity and Cost of Regulations. World Bank (2013)

New Zealand generally out performs Australia on the “ease of doing business” indicators. In 2014 it ranked 3rd in the world after Singapore and Hong Kong. In an area like ease of starting up a new business, it was found to take only one step, half a day and cost little or nothing in fees to get this done in New Zealand.

By comparison the average across the OECD was 7 separate procedures, 25 days and costs of around 32% of the firm’s annual income. Australia’s performance on starting up a new business suggested that it took at least three separate procedures, around two and a half days and about 0.7% of annual income in fees.

Business friendly regulations and policies

However, the act of starting up the new business is perhaps of less importance than the ability of the new owners to secure power, water, building approvals and the necessary licences to undertake the operations required to run the business. Here the worst performing areas for Australia were the compliance cost of trading across borders, paying taxes and registering property. For New Zealand it was getting electricity supply connected.

According to the World Bank it was taking an average of 5 separate procedures, 75 days and a cost of around NZD $45,721.50 to get a new electricity connection made in the city of Auckland. In Australia this process was found to take the same number of procedures and days, although at a lower cost of AUD $5,152.90. By comparison Singapore was able to connect electricity in about 38 days at a cost approximately 40% of that charged in New Zealand.

Australia’s compliance costs for trading across borders were found to be worse than the OECD average. The World Bank study found that to secure export permits it was requiring Australian firms to complete at least five separate documents and for imports seven documents. The average cost per container shipped from Australia was around US $1,150, and US $1,170 per container for imports. This compared to US $440 per container in Singapore and US $870 (export) and US $$825 (import) for New Zealand.

The time taken to export or import goods to and from Australia was around 8 to 9 days. This compared to only four days for Singapore. All of this highlights the importance of ensuring that government regulations are efficient and do not impose unnecessary compliance burdens or costs on business.

What is needed is not the removal of any regulation or “red tape” on businesses, particularly small firms, but “smarter” regulations. As the SEAANZ White Paper argues:

“While the cutting of ‘red tape’ is often used as a mantra by those seeking to lift the regulatory burden off the shoulders of SMEs, there are frequently few successful campaigns to cut red tape. This is because government regulation and compliance is typically put in place to protect the community, the workforce, consumers, the environment or other businesses. Some industries are more heavily regulated than others due to high potential for risk (e.g. air transport, construction, medical services and pharmaceuticals).”

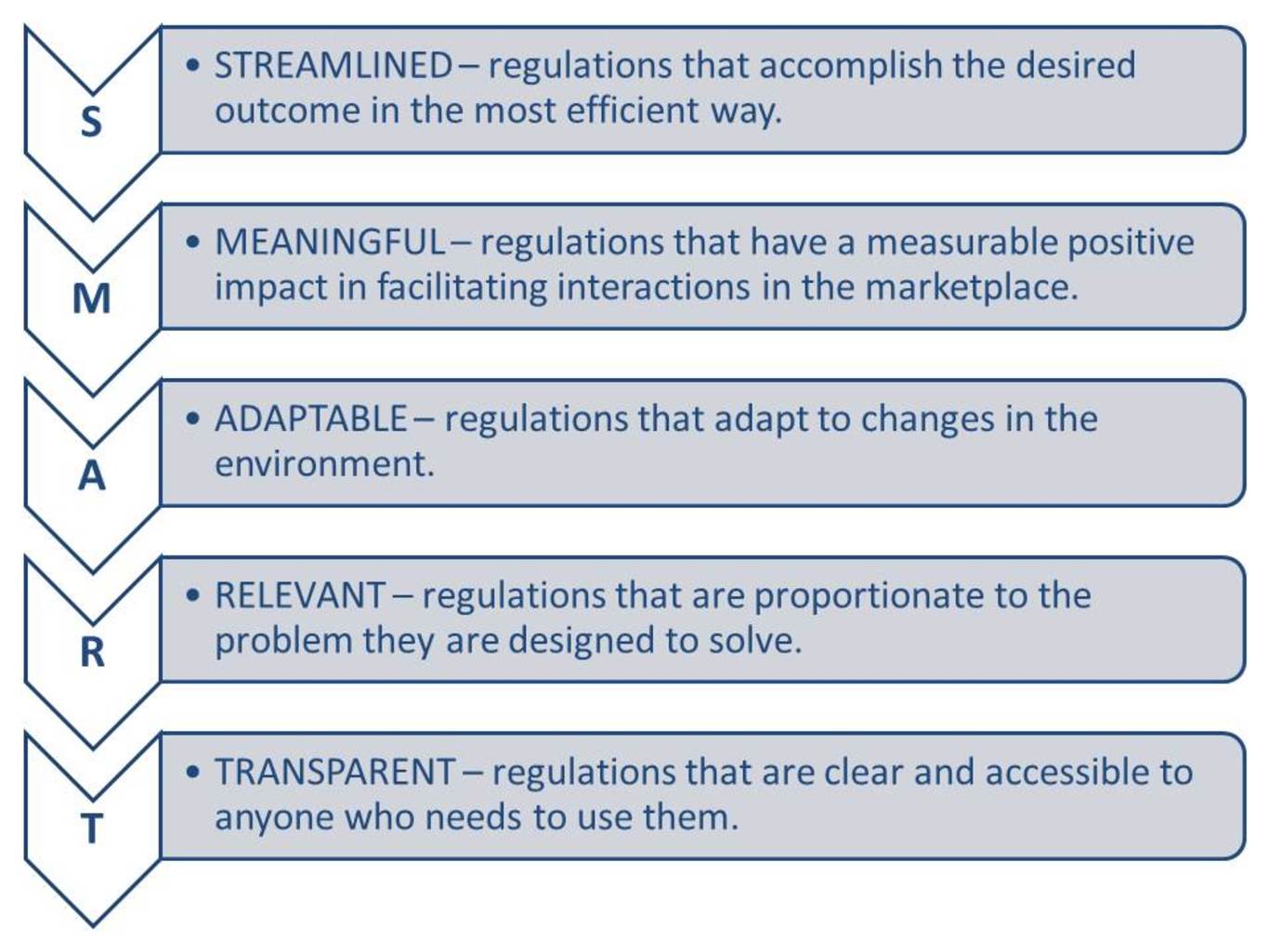

The World Bank suggests that business regulations should be streamlined, meaningful, adaptable, relevant and transparent. This forms the concept of “smart” regulations as shown in the following diagram.

SMART Regulations. World Bank (2013)

In other words it is not a matter of making government and bureaucracy smaller so as to get it out of the way, but to ensure that it is more efficient, and more responsive to the needs of the public and industry. Streamlining local, state and national government policies to reduce duplication, and shifting engagement with government online via “one-stop-shop” portals is one way that this might be achieved.

Taxation policy

Of all the areas of government regulation and compliance that raise the most discussion it is taxation policy. Yet it is important to recognise that while nobody likes to pay tax, without a well-managed taxation system the viability of the nation state is in serious jeopardy. Key considerations for tax policy in entrepreneurial ecosystems are how equitable are the taxes, do they provide incentives for new businesses to form, and do they disadvantage small firms?

According to KPMG the average corporate taxation rate for Australia and New Zealand over the period 2009-2014 has been around 30% which compares to 25.6% for the OECD, 22% for the European Union, 40% for the United States and 17% for Singapore over the same time period. This suggests that while Australia and New Zealand company tax rates are not the highest in the world, they are generally higher than the OECD and EU average.

The World Bank’s analysis of taxation compliance found that Australian businesses were paying around 47% of annual profit in taxes and making an average of 11 separate payments. This included company income tax, superannuation guarantee levy, state payroll tax, worker’s compensation, fringe benefits tax (FBT), land tax, municipal tax, vehicle tax, fuel excise, GST and taxes on insurance contracts. It was also estimated that this taxation compliance was taking an average of 105 hours per year for businesses to complete.

By comparison, in New Zealand companies were making only 8 payments. These included company income tax, the employer paid Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) levy, road user charges, interest tax, FBT, property tax, tax on cheque transactions, fuel tax, and GST (VAT). The average rate of company tax in New Zealand was estimated at 34.6% of annual profit, and it was taking around 152 hours per year to complete the compliance paperwork.

This compares to Singapore where only 5 taxes are paid each year and the time taken is estimated to be around 82 hours per annum. Overall, this suggests that countries such as Australia and New Zealand could improve their taxation systems with a view to reducing the amount of taxes that have to be paid, the rate of taxation and the time taken to complete the necessary paperwork.

It is particularly important to note that small businesses on average pay a much higher rate of company tax than their larger counterparts. This was a point raised by Dr Sergio Arzeni, Director of the OECD’s Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development at the G20 SME Conference last year. He told the conference that while compliance costs or “red tape” hit small firms around 10 to 30 times more than larger firms, the rates of tax paid were also unequal.

For example, he stated that while the average rate of taxation paid by SMEs across the OECD was around 30%, that for large firms was between 2% and 5%. This suggests that government policy could do much more to ensure that large firms are paying their fair share of tax rather than leaving the burden to fall disproportionately on the small business sector.

The importance of infrastructure

In addition to regulation and taxation policy the vibrancy of an entrepreneurial ecosystem is also dependent on the quality of infrastructure available within a country or region. According to the WEF, the main infrastructure critical to the growth of these ecosystems are transport (e.g. road, rail, sea and air), telecommunications (particularly broadband access), and utilities (e.g. electricity, gas, water, sewerage).

There is little doubt that the ability for business to perform at a globally competitive level is contingent on the quality of this infrastructure. This is something I wrote about in another article in “The Conversation” back in 2012. That article pointed to Australia’s ranking of 20th out of 142 nations as measured by the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Report, which noted that our infrastructure was lagging behind world’s best practice.

The latest Global Competitiveness Report ranks Australia in 22nd place and notes that the country’s position has been steadily worsening since 2009. Key areas of concern are labour market and wage setting “rigidities”, although it has excellent financial services, a sound banking system, excellent higher education and training sectors and the fourth lowest public debt-to-GDP ratio in the OECD. The report also points to concerns over Australia’s tax rates and regulations, government regulations efficiencies and infrastructure.

It scores Australia’s overall infrastructure in 35th place, which is behind New Zealand in 32nd the United States in 12th place, or Switzerland and Singapore in 1st and 2nd places respectively. Further, while the adoption rate of internet services is high, the internet bandwidth in the country is poor. Australia’s ranking in relation to international internet bandwidth (kb/s) per user is 39 out of 144 countries. This places us ahead of New Zealand (57th place), but well behind the majority of European Union (EU) states plus Hong Kong (ranked 2nd) and Singapore (ranked 4th).

It is critical to Australia’s long term economic growth and our ability to foster the next generation of globally focused, innovative and competitive industries to have world’s best practice infrastructure. Any failure by government to provide or facilitate such infrastructure will impede the emergence, growth and development of business.

This is particularly the case for high speed broadband services. The ability for young and growing small firms to remain competitive in the global economy is heavily dependent on their being able to access high speed broadband infrastructure. Increasing use of online services for e-commerce, e-business (e.g. supply chain management), e-tendering and e-marketing have made it imperative for SMEs to engage with the digital economy.

In the EU a target has been set for all Europeans to be able to access the internet with broadband speeds of more than 30 Mbps by 2020. The EU also plans to provide the majority of users with speeds of over 100 Mbps by the same date. This will be critical for SMEs engaging online business and marketing activities where a minimum requirement will be 100 Mbps for both uploading and downloading digital data.

Australia’s business community cannot afford to be left behind in relation to broadband infrastructure. It is a shame that the National Broadband Network (NBN) has been turned into a political issue rather than a significant investment for the future competitiveness of the national economy.

Key recommendations

The SEAANZ White Paper recommends that all government agencies and regulatory authorities should move towards a “digital by default” model of dealing with business online. Such online systems should also aim to achieve a “one-stop-shop” model for compliance issues. All efforts should also be made to achieve a “joined-up-government” approach, linking local, state and federal government agencies to reduce duplication and compliance costs.

Regulation of SMEs should be dealt with on “risked-based” model in which employees of regulatory authorities are empowered to adopt flexible and reasonable approaches to how they deal with small firms. This should follow an “educate and inform” approach, rather than treating all firms as posing the same threat. They should see their role as providing services not enforcement. This is consistent with the recommendations from the 2013 Productivity Commission Report into how regulators should deal with small business.

Conclusions

In order to foster a healthy and growing entrepreneurial economy it is necessary for government to ensure that they maintain efficient, effective, and easy to use services, and that compliance costs and regulations are managed intelligently. While regulation and taxation are necessary evils they should be designed to avoid unnecessary costs, inefficiency and duplication.

Infrastructure is also critical to business competitiveness. If road, rail, sea and air transportation systems are inefficient, congested or poorly maintained the net effect will be to strangle the ability of business to operate competitively. If telecommunications services, broadband, power and water infrastructure are unduly expensive, slow or ineffective, this will also impede the competitiveness of business.

If we take an ecosystem’s perspective, the ability of businesses to start-up, grow, employ people and generate economic growth, will be enhanced if the macro-conditions within their environment are appropriately configured. Poor infrastructure and excessive regulation and compliance costs will impede economic growth and stifle long term prosperity.