How do we understand race in the modern digital age? In our conversation on Wednesday about the essay “On Being White and Other Lies” by James Baldwin, we discussed the choice to become white when European immigrants reached American shores. These people gave up their unique heritages for homogeny. As James Baldwin wrote, “America became white because of a necessity of denying the black presence, and justifying black subjugation” (Baldwin 1). This led me to question how we see ourselves as Americans today, and the future of race in America because of this homogeny. As a midwesterner, I share many interests and speech patterns that are considered universally “American”. I love hot dogs and baseball games, I say “ope” in awkward moments with stranger, etc. But because of the institution of white supremacy, anything American has become synonymous with whiteness. As a false identity created to support racism, it is ironic that today it is popular for young white people to appropriate black culture.

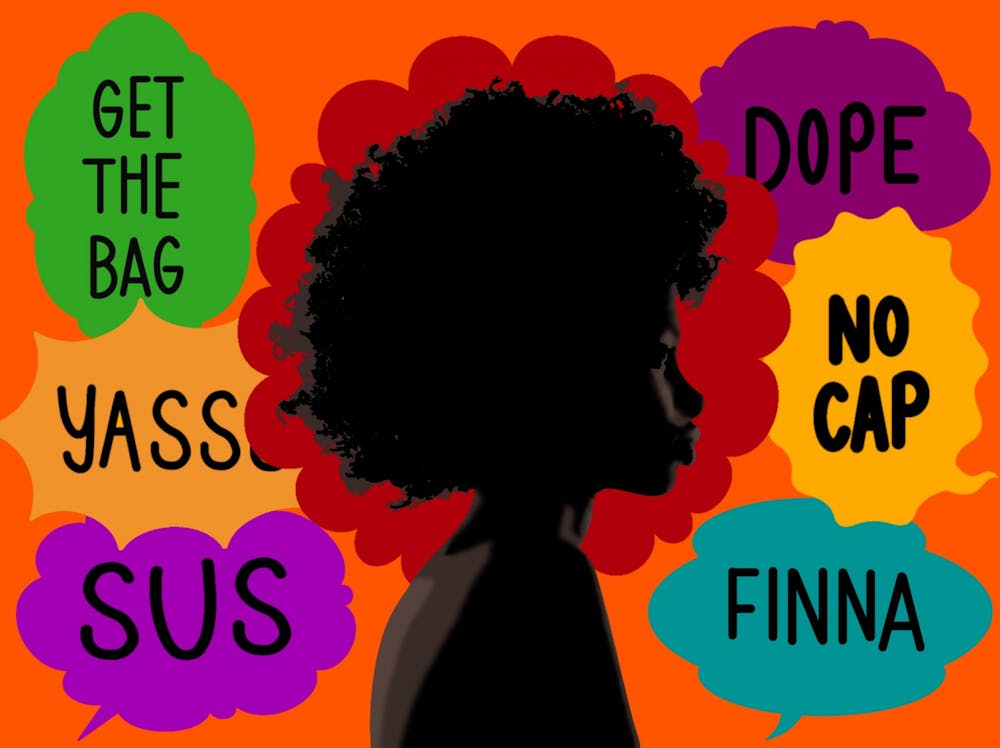

American pop-culture is becoming increasingly more homogenous, and it is harder and harder to separate internet slang from African American culture. Mainstream colloquialisms popularized on social media are drawn heavily from African American Vernacular English. Daily, I hear familiar words and sayings I remember from growing up, the way I speak with other black people, emerging as poor imitations from the lips of white students. I hear my culture distorted and appropriated, used like a knowing look, an offhand word or phrase thrown into a conversation as a reference of that one TikTok we’ve all seen (remember that meme?) like a joke we’re all in on. The AAVE is usually preceded by a pause, like a comedian before a punchline. An extreme example would be of the viral TikTok of a white woman describing her frustration with her concert tickets, exclaiming, “No like, I finna be in the pit” , which garnered an appropriate amount of backlash.

We see this in other ways online. If we think back to viral videos on vine or popular reaction pictures and gifs from the early 2010’s, most of these images were at the expense of a black person. A modern Jumpin’ Jim Crow – the image of blackness continues to be used as entertainment for white people. Baldwin equates the choice of whiteness to a “moral erosion”. He uses the example of black people in athletics, and discusses how white people watch in either relief or embitterment by the black presence on the team, but do not face what black athletes had to pay to get to that position because of white supremacy. Black bodies were used as commodities to build this country, and although slavery seems long ago the black body continues to be commodified: the product of our tongues (music, language etc), our hair, our lips, our curves, our style are sold on the market: lip fillers, BBLs, waist trainers, self-tanner.

With the appreciation/appropriation of blackness in mainstream American culture, does Baldwins assertion that “there is no white community” still ring true? This is a difficult question given the universality of American culture. I think that the problem of whiteness as described in Baldwin’s work has reached farther extremes than Baldwin could have imagined in the 21st century. Homogeny has eroded the uniqueness of black culture and commodified it for economic gain. Is this commodification and appropriation a symptom of the “crisis of leadership” ? That paradox that “those who believed that they could control and define Black people divested themselves of the power to control and define themselves” (Baldwin 5)? Possibly a lack of definition in white culture caused an reaching to other cultures for definition.

However frustrating and degrading cultural appropriation can be, African American culture’s integral role in making American culture is the fulfillment of Baldwin’s assertion that “We—who were not Black before we got here either, who were defined as Black by the slave trade—have paid for the crisis of leadership in the white community for a very long time, and have resoundingly, even when we face the worst about ourselves, survived, and triumphed over it.” (Baldwin 5). Black culture’s dominance in America is a testament to our resilience and is something to be proud of.

Some could say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but that might be a little too on the nose.