In the 1940s, during the midst of World War II, Notre Dame embarked on an ambitious campus beautification project, which would fill twenty empty niches on buildings around campus, including many that had stood vacant for decades. In 1943, classes in the Art Department were cancelled due to lack of fine art students. While such classes remained for the Architecture students, the faculty and artists in residence with the Art Department had some time on their hands to concentrate on the campus statue project.

The first building to see such an installation was the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. In May 1944, St. Joan of Arc and St. Michael the Archangel finally found their home at the east World War I Memorial Door. The Memorial door itself was originally added to the Basilica in 1924, left with empty niches for twenty years.

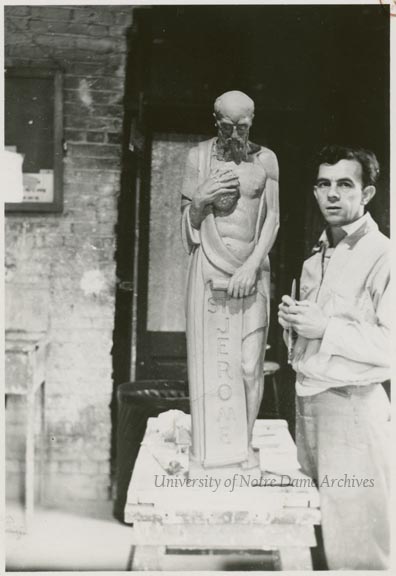

Few may have been “aware of the sculpture creations going on in the Old Natatorium Building behind the Dome.” Fortunately, Rev. John J. Bednar, CSC, sculptor of many of those statues, wrote a letter in 1980 to then-Notre Dame Magazine editor Ron Parent describing his involvement in this campus sculpture project. Below are excerpts from Bednar’s letter (at times Bednar refers to himself in the third-person):

“[I]t might be of interest to some that all the statues were done in artificial stone, a cement mix consisting of Portland cement, white cement, silica, marble dust, and for slight coloring, Burnt Siena powder, a warm brown color. The figures had to be made in clay from which a mold was formed for pouring the cement mix. Father O’Donnell would not consent to have the figures carved out of limestone – too slow and expensive a process. As it was, the niches on campus buildings had been neglected for too many years. The World War I Memorial had the names of Joan of Arc and St. Michael carved in Gothic script below the niches in 1924, empty niches, and now we were in the middle of World War II when John Bednar filled those two niches with their namesakes!

“The opportunity to fill all the empty niches on campus facades came when Father Szabo of South Bend brought Eugene Kormendi to meet with John Bednar, the sculptor in the Art Department and to see if Kormendi could obtain any sculpture commissions from the University, a likely outlet for a sculptor. I suggested that we could fill all the empty niches on the campus which I had been eying for years. I had been studying sculpture under the tutelage of Chicago’s foremost sculptor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, (received my M.F.A. in sculpture in 1940 and had introduced sculpture into the program of the Art Department at Notre Dame the same year.) The Szabo-Kormendi visit was perfectly timed for a sculpture project on the campus.

“A reliable witness to the production of the campus sculptures was Tony Lauck, a Moreau seminarian at the time and a sculptor of merit, who also wished to work in the Bednar-Kormendi studio on his own project, a huge block of wood for a standing figure of Christ. Permission granted and Tony brought two other seminarians to help him with a double-handled cross-cut saw for the preliminary shaping of the Christ figure. A bronze casting was made of that wood carving which can be seen today on the grounds of St. Patrick’s Church, South Bend.

“The St. Jerome statue on another Dillon wall, showing the great Biblical Scholar beating his chest with a rock instead of a scourge, Bednar shipped to Indianapolis before installation in the niche. I won a prize in sculpture at the John Herron Art Museum in a juried exhibition The $150 prize paid for the round trip and for the clay, the cements, marble dust etc., and brought back the approval of the jury.”

Among the Sculpture on Campus Installed in the 1940s:

Works by Eugene Kormendi:

Law School Building – “St. Thomas More”; “Christ the King” [due to deterioration, these two statues were disposed of during the 2010 construction of the Law School addition]

Alumni Hall – “The Graduate”

Dillon Hall – “Commodore Barry”

Lyons Hall Arch – “St. Joseph with Lilly”

Morrissey Hall – “St. Andrew”

Rockne Memorial Entrance – “St. Christopher”

St. Liam Hall Infirmary – “The Good Shepherd”; “St. Raphael the Archangel”

Works by Rev. John J. Bednar, CSC

Alumni Hall Courtyard – “St. Thomas Aquinas”; “St. Bonaventure with Cardinal’s Hat”

Dillon Hall – “St. Augustine, Bishop” (courtyard); “St. Jerome”; “Cardinal Newman, Scholar” (above west doorway)

Basilica of the Sacred Heart – “St. Joan of Arc”; “St. Michael Archangel”

Works by James Kress (Detroit)

Howard Hall – “St. Timothy”

Sources:

GBED 1/01 [photographs and letter from Bednar to Parent]

Scholastic

GNDS 24/49

GJJC 1/36

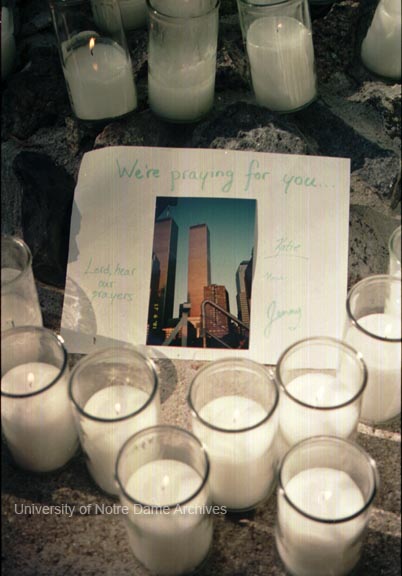

Vigil Procession after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks

Vigil Procession after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks