Notre Dame celebrates 40 years of coeducation this fall. While the undergraduate women who arrived in 1972 were the first class to matriculate in the regular academic year, women had been earning bachelors’, masters’, and doctorate degrees since 1917 through the Summer School Program. One of those women gained a bit of fame during World War II because she was an unlikely aviatrix and aeronautical expert.

Sister Mary Aquinas Kinskey, OSF, earned a bachelor’s degree from Catholic University in 1926. She became a teacher and her interest in aviation stemmed from the enthusiasm for the subject from her students. In order to best teach her students, she wished to learn as much about the subject as possible. In 1942, she earned a Master of Science in Physics cum laude from the University of Notre Dame. Her dissertation was entitled “Electron Projection Study of the Deposition of Thorium on Tantalum.” Wanting hands-on aviation experience, Sister Mary Aquinas learned to fly in 1943.

Source: Library of Congress, FSA/OWI Collection

That summer, she taught aviation at Catholic University and was involved in training through the Civil Aeronautics Authority. Below is an announcement regarding Sister Mary Aquinas’ activities published in Scholastic, October 1, 1943:

One of Notre Dame’s religious alumnae who is doing her part in the War effort is Sister Mary Aquinas, the “flying nun.” Sister Mary Aquinas, who received her master’s degree in physics from the University, is an educational adviser to the C.A.A. in Washington. Her aeronautics course at the Catholic University of America is one of the first, if not the first, sequence of such courses for Teacher Training in universities during the summer sessions. The Sister, who believes in practicing what she teaches, is a flier. She often takes her classes on inspection and demonstration tours through aircraft factories and airports. Her group of black-hooded nuns are a familiar sight in these places.

Source: Library of Congress, FSA/OWI Collection

In 1957, “the Air Force Association gave her a citation for her ‘outstanding contributions’ to the nation’s security and world peace” [“No Glamor Girl”]. As part of the honor, Sister Mary Aquinas had the opportunity to fly in a T-33 jet trainer and take the control for much of the flight, making her the first nun to fly a jet.

The women with heart necklaces are Sisters of the Holy Cross.

Source: Library of Congress, FSA/OWI Collection

Sister Mary Aquinas was the subject of a 1956 television program The Pilot. Her moniker as “The Flying Nun” leads many to believe she was the inspiration of the 1967-1970 television show starring Sally Field. Furthering the thought there might be a connection, the television show was based on a The Fifteenth Pelican, a book by Tere Rios Versace, who also researched the life of Sister Mary Aquinas for an unpublished biography. Versace’s papers can be found at the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives.

Sources:

“The Fighting Irish at the Fronts,” By Jim Schaeffer, Scholastic, October 1, 1943, page 9

September 3, 1942 Commencement Program [PNDP 1300]

“Sister Mary Aquinas, ‘The Flying Nun,’ Says Air-Minded Child Is a Happy Child,” by Margaret Kernodle, AP Features Writer, Lewiston Morning Tribune, Lewiston, Idaho, August 8, 1943

“Navy Invites Nun to Pilot Jet,” Lodi News-Sentinel, Lodi, California, July 25, 1958

“‘No Glamor Girl,’ Flying Nun Says,” by Bob Considine, The Milwaukee Sentinel, September 8, 1957

“Three Sisters, Three Stories, Touching Lives,” Silver Lake College New Directions, Fall/Winter 2008-2009

“Sister Mary Aquinas Is Dead; Pilot Inspired TV ‘Flying Nun,'” The New York Times, October 23, 1985

The Wisconsin Historical Society

Photos of Sr. Mary Aquinas from the Library of Congress are in the public domain

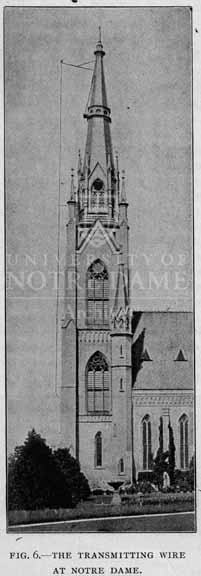

laboratory in Science Hall (now called LaFortune Hall) to other rooms in the building. They succeeded in sending signals from Science Hall to Sorin Hall, then from the flag pole to the Novitiate (which was located near present-day Holy Cross House). “They found that everything worked perfectly well here, and so they set about their last and greatest trial. This was to send a message from Notre Dame to St. Mary’s Academy which is more than a mile away from the University [, using the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for the transmission wire]. … This is the farthest distance a message has been sent in this country as far as we know and the boys in the scientific department feel highly elated over their success.” [Scholastic, 04/22/1899, page 494].

laboratory in Science Hall (now called LaFortune Hall) to other rooms in the building. They succeeded in sending signals from Science Hall to Sorin Hall, then from the flag pole to the Novitiate (which was located near present-day Holy Cross House). “They found that everything worked perfectly well here, and so they set about their last and greatest trial. This was to send a message from Notre Dame to St. Mary’s Academy which is more than a mile away from the University [, using the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for the transmission wire]. … This is the farthest distance a message has been sent in this country as far as we know and the boys in the scientific department feel highly elated over their success.” [Scholastic, 04/22/1899, page 494].