Post by Jason McLachlan, University of Notre Dame Professor

On Friday, we had a film crew from a local natural history show “Outdoor Elements“ on campus to film a couple of segments on PalEON. I led a segment on the changes in vegetation from the era of European settlement to the present and Sam Pecoraro led a segment on tree-rings. The host and director, Evie Kirkwood, asked each of us to come up with some photogenic activities and to think about why the Outdoor Elements viewers should care about our work.

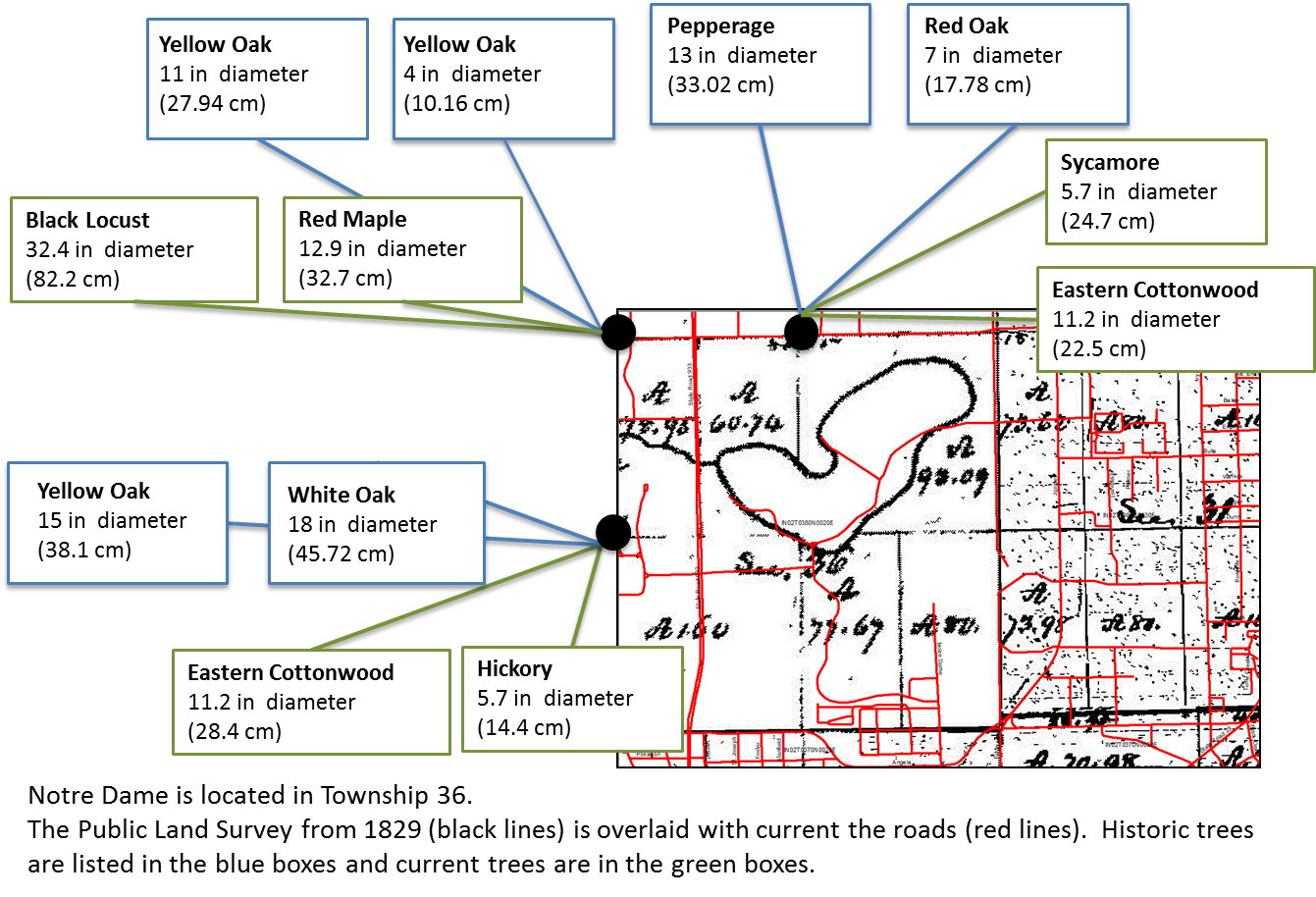

(1) The first part was easy. Jody and Zoe helped me pull together the settlement-era PLS survey data for the area that would later be the Notre Dame campus. Zoe and Jody overlaid the modern campus road system on top of the original survey map and the transition is striking. Back in 1829, when William Brookfield surveyed the area, Saint Joseph’s Lake and Saint Mary’s Lake are shown as a single lake (which was separated in the mid-1800s to reduce swampy lake margins). The creek draining this lake into the Saint Joseph River is now an underground culvert.

Resurveying the corner trees shows a transition to smaller trees in places that are now forested, and a transition to larger trees in open grown or ornamental settings. The broader settlement-era landscape includes long-gone features like the “Portage Prairie” along the canoe portage to the Kankakee River. Evie asked us if any of the original settlement-era trees still existed. The only plausible candidate we know of is this white oak on campus. It’s size and open grown form make it a plausible survivor, but it’s hollow, so we don’t really know if it was around when William Brookfield first passed by.

Meanwhile, Sam cored trees at the resurveyed PLS points for the camera. Sam cuts a rugged figure in his field gear (no picture available) and he is far more articulate than I am. Chelsea Merriman had earlier helped him prepare replicate cores for analysis, so, like Julia Child, Sam was able to instantly pull out sanded and counted tree-cores for the show.

(2) Getting our message across was much clumsier for me. Evie Kirkwood is a real pro and she made it as easy as possible for us, but academics are trained to be bad communicators, I felt really stumbly trying to get the magnificence of PalEON across in 7 minutes.

Here’s what I wish I’d said:

“We care about this for two reasons: First, we think we know our home, but what we think is permanent is transitional. Everyone hates to see changes in their town, or their neighborhood, or the landscape of their youth, but these things always change. Even when William Brookfield surveyed this township in 1829, it was changing, recovering from the French and Indian wars. (Everyone should read Richard White’s, “The Middle Ground”). PalEON shows us the pace and character of this change, so we can understand where we live.

Second, we know a lot about how the world will change moving forward, but not enough. The models we have for anticipating our impact on the atmosphere and the biosphere are stunningly clever and powerful. But they are also too simple (they are supposed to be simple). I’m not sure if we will ever provide the accurate forecasts that policymakers seek, but our best effort will combine these models with data on how ecosystems really change. That’s what PalEON does.”

Here’s what I actually said:

Actually, I don’t remember what I actually said. I was really nervous. What I was thinking was: “Am I supposed to look at Evie or the guy with the camera? Did I just stick my arm right in front of Zoe’s face? Shit. I forgot to mention the changing stem densities! Does this new haircut make my face look fat?”

Luckily for me, Evie is a good editor; we gave them a lot of good visuals; and Sam is a natural in front of the camera. Everyone says I didn’t look nervous and I made sense. We’ll see when the show hits the air in 2014.