Ever since Pope John Paul II’s 1987 social encyclical, Sollicitudo rei socialis (On Social Concern), the term “solidarity” has become a key principle of Catholic social doctrine. In paragraph 40, the pope writes:

“Solidarity is undoubtedly a Christian virtue… In light of faith, solidarity seeks to go beyond itself, to take on the specifically Christian dimension of total gratuity, forgiveness, and reconciliation. One’s neighbor is then not only a human being with his or her own rights and a fundamental equality with everyone else, but becomes the living image of God the Father, redeemed by the blood of Jesus Christ and placed under the permanent action of the Holy Spirit. One’s neighbor must therefore be loved, even if an enemy, with the same love with which the Lord loves him or her; and for that person’s sake one must be ready for sacrifice, even the ultimate one: to lay down one’s life for the brethren (cf. 1 John 3:16).”

There is nothing new to the pope’s teaching on solidarity whereby one offers his or her life for the sake of another or for one’s community. When the Babylonian Jews turned to the God of Israel, they were told: “Promote the welfare of the city to which I have exiled you; pray for it to the LORD, for upon its welfare depends your own.” (Jeremiah 29:7) Jesus makes it a central message of his preaching and passion to extend this desire especially towards his enemies. St. Paul beautifully highlights the continuity and difference between the old and the new, the God of the philosophers and the God of Israel, when he teaches: “Indeed, only with difficulty does one die for a just person, though perhaps for a good person one might even find the courage to die. But God proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us.” (Romans 5:7-8)

In the context of modern human rights discussions, this teaching provides a theological vision of rights that goes beyond mere restitution and justice as the guiding principles for securing rights for everyone to include the higher principles and virtues of solidarity and love. Much of the literature on rights, when it is not overly abstract, focuses on addressing the structural and institutional dimensions of the question. This is certainly a necessary component. John Paul II speaks about this in terms of “structures of sin” and “evil mechanisms.” However, the personal or individual dimension of the question should not be overlooked in the effort to rectify political and social arrangements. In fact, the personal dimension is the foundation to the discussion from a Christian perspective because it begins with the real event of conversion from sin. This is why the attitude or virtue of solidarity is so important to the discussion; it is indicative of a heart being turned from stone to flesh that “is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortuntes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and preserving determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we really are all really responsible for all.” (par. 38)

The conversion leading to solidarity turns away from the desire for profit and power by seeking “the good of one’s neighbor with the readiness, in the gospel sense, to “lose oneself” for the sake of the other instead of exploiting him, and to “serve him” instead of oppressing him for one’s own advantage.” The late pope goes so far as to say that the influential and wealthy have a duty to the weaker in society in that they should “be ready to share with them all they possess.” This last claim is clearly an illustration of what a Christian vision of human rights looks like. It entails sacrifice.

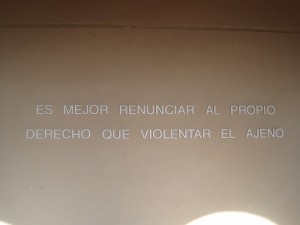

It is no surprise then that this same teaching appears on the walls of the cloister at the Dominican priory of San Esteban in Salamanca. The great theologians who first began a serious discussion of natural rights for all persons, regardless of creed, did so from a thoroughly Christian perspective. In the case of those engaged in a licit war, which should always be constrained by Christian values, Vitoria writes: “They must always be prepared to forego some part of their rights rather than risk trespassing on some unlawful thing, and always direct their plans to the benefit of the barbarians rather than their own profit, bearing constantly in mind the saying of St. Paul: ‘all things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient’ (1 Cor. 6:12).” (Relectio de Indis q.3, 2)

Vitoria presents this teaching under his second possible legitimate title for waging war–the spreading of the Christian religion. What is significant is that he departs here from a long-standing tradition within Latin Christendom that legitimated the right of preaching over and against that which obstructed it; namely, the idolatry and rites of unbelievers. In a reflexive move, Vitoria turns the issue back to Christians by stating that “it may happen that the resulting war, with its massacres and pillage, obstructs the conversion of the barbarians instead of encouraging it.” There is no doubt that Francisco Pizzaro’s conquest of Peru would have been fresh on his mind here as an example of such an obstruction.

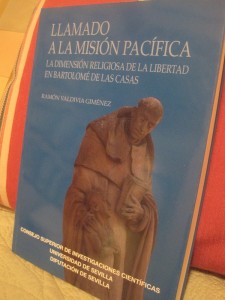

Unfortunately, Vitoria did not go far enough in his implementation of the solidarity principle with regard to the right of preaching. His recognition of the rights of natives to receive the Gospel freely was not absolute but conditional. Earlier in that same discussion, he says that the Spaniards “may preach and work for the conversion of that people even against their will.” On this point, disciples of Vitoria such as Domingo de Soto, Melchor Cano, and Bartolomé de Carranza were not in agreement. Instead, they followed Las Casas in recognizing that every single right of Christians, even the most important one given by Christ to preach, should be renounced if it entails violating the rights of another. Of course, this teaching came from Christ himself when he commissioned the twelve: “Whoever will not receive you or listen to your words–go outside that house or town and shake the dust from your feet.” (Matt. 10:14) Who better to teach perfect solidarity than the Lord himself by showing his disciples in word and deed that the greatest right of all may need to be renounced, even for the sake of one’s enemies.