Black Friday doesn’t seem to be going anywhere as an American cultural phenomenon. In fact, what used to be a one-day kickoff to the Christmas shopping season on the Friday after Thanksgiving has become a frenzied four-day shopping weekend culminating in what’s recently been dubbed Cyber Monday, the biggest online shopping day of the year. This past weekend, many retailers even offered enticing discounts on Thanksgiving evening itself, so that while some families enjoyed pumpkin pie and conversation, retailers like Walmart were processing “nearly 10 million register transactions” and rang up “almost 5,000 items per second.” With spending estimated at $59.1 billion, up 12.8 percent from last year, its hard not to be unsettled by American materialism.

Earlier this month, in his address at the fall general assembly of U.S. bishops, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, Apostolic Nuncio to the United States suggested that while “American ways and styles of life marked by materialism and consumerism…have contributed to leading her astray from the values of the Gospel. Yet, these Gospel values, by the grace of God, although strongly confronted by secular society, are still very much alive in the Church in America.” Perhaps one of the most hopeful ways in which Americans are embodying these Gospel values in response to materialism and consumerism is through an alternative, even subversive, form of spending: voluntary charitable giving.

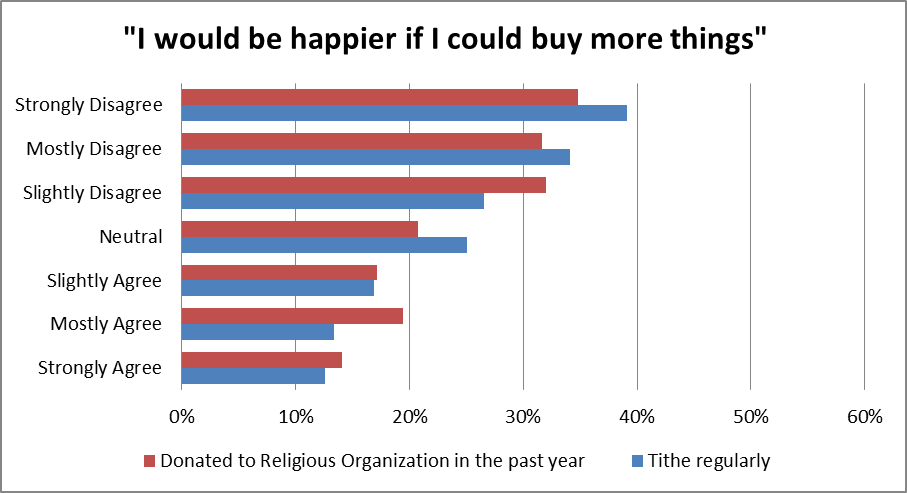

One of Brian Starks’ findings in his newly published report on the Catholic giving gap is that those who are less materialistic in their values are more likely to be engaged in charitable giving, as the attached graph from that report suggests.

But in a very real way, charitable giving also financially limits those who give to such causes from pursuing materialistic lifestyles. The report’s findings highlight the twofold tension between materialistic values and charitable giving. On the one hand, those who reject materialistic values will presumably have more money to give to charity, insofar as money not spent on material possessions is “freed up” for another purpose, such as monetary giving. On the other hand, those who give more also presumably reduce the amount they can spend on material goods, insofar as money allocated for charitable giving is “tied up” from material spending.

The choice to give charitably invites a reorientation toward non-material values, and hopefully in religious communities, toward “Gospel values” which Archbishop Viganò contrasts with “American ways and styles of life marked by materialism and consumerism.” One’s actions are a concrete statement to and for oneself about the prioritization of values such as generosity and concern for the needy over materialistic values.

Put simply, one way of simplifying your life is to give your money away.