When I read eBay v. MercExchange in isolation, I did not appreciate its significance. I found this article (copied below) that helped me understand that the eBay case represented a significant departure in previous practice. The Court recognizes, and this article emphasizes, that it was a general rule in the lower courts to grant injunctive relief after the patent-holder makes his case for infringement. The author describes it as “virtually unheard of for a district court to deny a victorious plaintiff a permanent injunction in patent infringement case.”

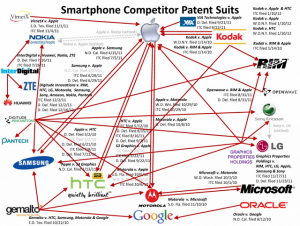

After the eBay case, from May 2006 to April, 2011, there were 131 cases where a permanent injunction was issued and 43 cases where a permanent injunction was denied (25% denial rate). The author, writing on the 5th anniversary of the case, explains what negative effects replacing this general rule with the four-factor test has had on patent practice.

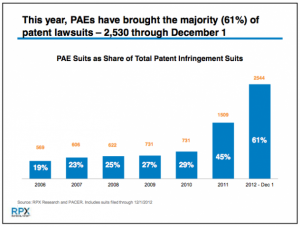

The Court’s decision may have been motivated by the need to deal with ‘patent trolls.’ The District Court’s application of the four-factor test in eBay seemed to be concerned with this. It held that the patent-holder’s “willingness to license its patents” and “its lack of commercial activity in practicing the patents” would be sufficient to establish that the patent holder would not suffer irreparable harm if an injunction did not issue. The Supreme Court said that this application was incorrect, and noted that such a rule would affect parties like university researchers and independent inventors. Justice Kennedy, in his concurrence, expressed a concern over the growing industry of ‘patent trolls,’ and flagged the issue for district courts to consider the nature of the patent and the patent-holder when applying the four-factor test.

The author admits that the decision had effects on ‘patent trolls’: “removing the presumption of irreparable injury from the equitable balancing creates the near-impossibility that a company focused solely on monetizing its patents through licensing could not be made whole through money damages alone.”

He argues, however, that the decision also has unintended effects.

The biggest effect is increased cost for patent-holders. The author explains one possibly nonobvious advantage of a permanent injunction over an award of damages is the district court’s continuing jurisdiction over the case when a permanent injunction is granted. Redressing a subsequent infringement is cheaper and quicker when a permanent injunction is in place than having to bring a new case. Just satisfying the four-factor test is more expensive for all parties because it requires proof of non-economic factors such as loss of goodwill or loss of market share.

According to the author, the change to the four-factor test and the fact that district courts’ decisions are reviewable only for abuse of discretion caused an increase in parties’ desire to find alternative means for dispute resolution where it is available. He asserts that the International Trade Commission (ITC) has become a far more desirable forum for patent owners, both non-practicing entities (includes ‘patent trolls’) and practicing entities alike. This is due to the ability to obtain an exclusion order. This option, however, is only available for patent-holders when infringing-goods are being imported into US.

While, the author is probably a little biased because his firm represents patent-holders (presumably some ‘big players’), I found it helpful in explaining the effects of the eBay case.

http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2011/05/15/happy-5th-anniversary-ebay-v-mercexchange/id=16894/