This article is interesting. Qualcomm is making money from licensing its products, but companies that use their products, including Apple, have filed suit. The licensing agreements have shown to be lucrative for Qualcomm and a bit much for the companies paying for the license.

Qualcomm is again under attack for living large off its patent portfolio

Its biggest customer, Apple, is suing it for $1bn

“SHOULD five per cent appear too small, be thankful I don’t take it all.” The Beatles wrote “Taxman” in 1966 to protest at Harold Wilson’s exorbitant “supertax” rates. Critics of Qualcomm, the world’s biggest chip-design firm, would say the lyric is a clue to the company’s business practices. Its methods have attracted a barrage of legal complaints. The latest came on January 25th, when Apple, a smartphone maker, sued it in China for abusing its clout in mobile processors and demanded 1bn yuan ($145m) in damages. Just days earlier Apple had filed a similar lawsuit in California asking for $1bn.

America’s Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a separate complaint against the firm this month. In late December, the equivalent body in South Korea fined it a whopping $853m, which hurt its quarterly results, announced this week. These cases follow two similar ones in 2015: Chinese regulators imposed an even higher fine, of $975m; and the European Commission raised formal objections about how Qualcomm was selling its chips.

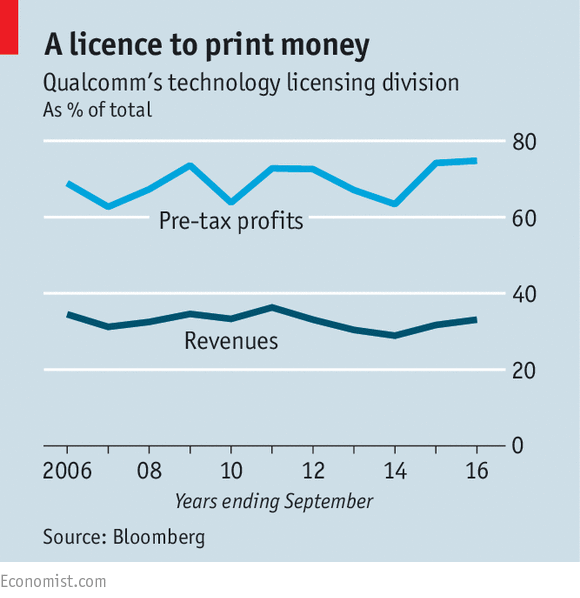

Qualcomm is no household name, but most people with mobile phones use its technology. It is estimated to provide up to four-fifths of essential types of baseband processors, the chips that manage a device’s wireless connection. These and other chips generated two-thirds of the firm’s revenues of $23.6bn in 2016. But the secret to its profits of $5.7bn is the way it licenses its intellectual property (see chart).

Qualcomm owns thousands of patents on technology deemed “essential” to build phones compatible with wireless standards. All the cases revolve around the peculiar model of how Qualcomm licenses these patents. It does not make them available to rival designers of chips and other components, but only to device-makers. These usually pay for the entire patent portfolio, rather than individual patents. And Qualcomm typically charges a percentage of the total selling price of a device—5%, according to insiders.

Combined with Qualcomm’s dominant position in baseband processors, the FTC argues, this set-up enables all kinds of abuses. In particular, it alleges that handset brands have little choice but to sign up to onerous licensing conditions in order to get the chips they need. Apple, among other things, claims that per-device royalties mean Qualcomm is taxing its innovation: it must pay up for new features, such as a new kind of camera, even if these are unrelated to Qualcomm’s patents.

Such accusations are not new. In the past Qualcomm has defended itself by arguing that its approach makes life easier for all involved: licensing patents for individual components would be too complex. As for the FTC’s allegation of monopoly abuse, Qualcomm said that it “has never withheld or threatened to withhold chip supply in order to obtain agreement to unfair or unreasonable licensing terms.”

The courts will now have to sort all this out. If legal battles are multiplying now, it is because the world is in a way “done” with smartphones, says Stéphane Téral of IHS Markit, a data provider. Slower growth and tighter margins have device-makers searching for ways to cut costs.

Apple’s cases are the biggest danger for Qualcomm: the iPhone-maker is its largest customer. Stacy Rasgon of Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm, describes Apple’s lawsuits as an “all-out assault” on Qualcomm’s licensing model. But the firm has shown that it can recover from crises by developing new technology and making clever acquisitions. Although regulators have yet to approve the deal, the firm in October bought NXP Semiconductors, a chip designer, for $47bn, which gives Qualcomm a foothold and lots more intellectual property in two promising markets: chips for cars and connected devices, collectively called the internet of things. The world may be “done” with smartphones, but the taxman is likely to remain a force.

Correction (Feb 8): A previous version of this piece stated that in 2015 the European Commission had found Qualcomm guilty of having sold chips below cost to hurt rivals. In fact, the EU had released its statement of objections, or its preliminary concerns, about how Qualcomm was selling its chips. This has been corrected.