When reading the first part of Go Tell It on the Mountain and Field’s piece “Pentecostalism and All that Jazz: Tracing James Baldwin’s Religion” I noticed many connections between religion and the Bible and Baldwin’s literary work. One that particularly caught my attention was the prevalent state of nakedness that dominated John’s feelings. On page 38, John stresses about what he would have to do if his mom was not feeling well. “He would have to prepare supper, …take care of the children…and be naked under his father’s eyes” (Baldwin, p. 38). When he looks at his baby picture in his house, he feels the shame of his nakedness in comparison to his siblings’ nakedness, even though he is a baby. Baldwin writes, “But John could never look at it without feeling shame and anger that his nakedness should be here so unkindly revealed” (Baldwin, p. 26). A lot of John’s feeling of nakedness reminded me of the origin and creation story with Adam and Eve. In the same way that Adam and Eve, once they committed original sin, became aware of themselves, their bodies, and their shame; they hid their naked bodies from each other and were overcome with vulnerability and guilt. The portrayal of John’s character is done similarly. In every example in which John acknowledges his nakedness, he feels shame and this nakedness and shame is tied to John’s sin. Like Adam and Eve, John submits to the temptations of his sexuality, has sinned, and now feels shame and guilt. John’s sin, not only his masturbation but his true sexuality, that being homosexuality, makes him feel shame in the world and this shame appears to him to be very visible to everyone. John is always under the assumption that others know of his sin, especially his stepfather. Now not only must he stand before God the Father on judgment day but must also stand before his step-father, naked and exposed. This also connects to a larger theme in which religion and the institution of the Church often view and depict sexuality outside of the tradition of the man and woman and outside of marriage to be shameful. These boundaries and standards of religion and the Church prevent people like John from having good relationships with the Church, religion, and even himself. I am curious to see how much this theme of nakedness and shame similar to the shame of Adam and Even when they committed their sin of temptation expands for John when he continues to explore his sexuality throughout the novel.

Month: September 2023

“You taught me language, and my profit on’t/Is, I know how to curse” : A comparison of the literary philosophies of James Baldwin and Richard Wright

Baldwin and Wright respond to an intellectual landscape with limiting depictions of blackness in differing ways. Both authors agree that not only do white authors dehumanize and demonize African Americans in their work, but African American writers themselves write narratives that pander to a white audience. As black men engaging with a Eurocentric intellectual tradition, they take on the role of Caliban, (from Shakespeare’s The Tempest) using the language of his master, Prospero, against him. Their approaches to combatting eurocentrism through their literature display differing interpretations of black political thought.

Richard Wright characterizes African American literature as lacking in “forthrightness and independence. ” (Intro, X). In his essay “Blueprint for Negro Writing,” he writes, “Negro writing in the past has been confined to humble novels poems, and plays, prim and decorous ambassadors who wend a-begging to white America… dressed in the knee-pants of servility… For the most part these artistic ambassadors were received as though they were French poodles who do clever tricks.” Their writing centered intelligent, tame protagonists who are led to an uncharacteristic act of violence, but Native Son does the opposite to expose the effects of the socioeconomic reality imposed on the negro. Through the character of Bigger Thomas, Wright takes on a philosophy of Afro-pessimism, arguing that due to the ongoing effects of racism, colonialism, and the history of slavery in the United States, the Negro is driven to violence. The character Bigger in Native Son, internalizes and lives out this philosophy and believes that “the moment he allowed what his life meant to enter fully into his consciousness, he would either kill himself or someone else” (Wright ).

In comparison, Baldwin, an avid reader, enjoyed books written by white authors and art coming out of Europe growing up. His appreciation for the works of authors like Henry James is evident in the quality and artistry of his written work. However, he knew himself to be “a kind of bastard of the West.” As a black man, he brings to the western tradition a “ a special attitude.” “These were not really my creations” he writes, “they did not contain my history; I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself.” Because he is not white, he cannot claim these great writers and artists as intellectual predecessors. In accepting this outsider perspective, he can freely and perpetually criticize the country which he loves so dearly. Baldwin admits that he had fear for both white and black people, but to submit to that fear, “gives the world power over him.”

This is the key difference between Baldwin and Wright’s work is that where Baldwin is optimistic yet critical of his country, Wright exposes the injustices of his country, and accepts them as unchangeable fact. As Baldwin writes, “[protest novels] emerge… A mirror of our confusion, dishonesty, panic, trapped and immobilized in the sunlit prison of the American dream.” The failure of Wright’s perspective is that it cannot see beyond the Master-Slave dialectic, submitting to the idea that racism is a fixture of American society, and we have to work within this system. Baldwin’s philosophy gives us hope. His job as a writer is to “examine attitudes, to go beneath the surface, to tap the source,” and reveal the context of the Negro problem: the history, traditions, customs, the moral assumptions and preoccupations of the country. Using his unique perspective, he reveals complexity in Negro life, pushing against the dehumanizing assumptions of the Eurocentric framework and revealing its limitations.

James Baldwin: A Prodigal Son?

I found James Baldwin’s reflections on the tumultuous relationships with both of the father figures in his life in “Notes of a Native Son” and later in “Alas, Poor Richard” to be some of the more powerful pieces we have read thus far. It is especially striking to consider the similarities between his stepfather David Baldwin and mentor Richard Wright, as they both had profound impacts on the life and work of James Baldwin long after they passed.

To say the least, Baldwin did not have a picturesque relationship with either of these individuals. Baldwin recalls only one time in all his life with his stepfather David in which they had really spoken to one another. Baldwin adds that he cannot remember a time when he and his siblings were happy to see their father return home (79). He experienced a similar distancing with Wright, noting that their dialogues “became too frustrating and acrid” (265). Tragically, Baldwin reconciled with neither paternal figure in his life before they died.

I would argue that Baldwin saw a bit of himself in both David and Richard, and this realization of similarity is part of the reason for their tense relationships. By this I mean, Baldwin watched how qualities of these father figures eventually led to their deaths, in a physical sense for his stepfather and a metaphorical one for his mentor as an author. I think he feared that, because of their likeness, he might face a similar fate. Baldwin explains that David “lived and died in an intolerable bitterness of spirit” that frightened him “to see how powerful and overflowing this bitterness could be” and it was now his (65). In a similar vein, of Wright Baldwin says, “They despised him… It was certainly very frightening to watch. I could not help feeling: Be careful. Time is passing for you, too, and this may be happening to you one day” (266). For Baldwin, David and Wright are comparable not only in their relationship to him as some sort of distorted father figure but also in that they serve as a warning. Yet, despite the turmoil they caused him, he longs for their presence. Baldwin laments, “Now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now” (84). Similarly, he speaks to Wright: “Whoever He may be, and wherever you may be, may God be with you, Richard, and may He help me not to fail that argument which began in me” (258). This desire for reunion with David and Wright evokes for me the image of the prodigal son… has he returned home?

The Power of Literature in Perpetuating or Challenging Racism in America

In “Black Boys and Native Sons” by Irving Howe, Howe presents James Baldwin’s strong assertions about Richard Wright’s protest novel Native Son. Baldwin writes that although the novel was “undertaken out of sympathy for the Negro,” presenting Bigger as a monster, “a social victim or mythic agent of sexual prowess” confined Bigger as a Negro to “the very tones of violence that he [as a Black man] has known all his life.” The portrayal of Bigger Thomas and the implications that it provided for Black men and ‘Blackness’ was a topic I often questioned once completing the novel. Like Baldwin, I too wondered, if Wright’s goal was to show the negative effects of white America on Black Americans, then why paint the picture that Blacks were the problem in society? As we further discussed in class, Wright’s depiction of Bigger Thomas only further perpetuated the stereotype that white people had of Black men being violent and dangerous. Native Son articulated everything that Americans were thinking but were afraid to say out loud and because it did that, and confirmed a harsh and negative stereotype of Black culture, it was way more regressive than it was progressive. It presented a sociological issue that I found could not be fixed or at least could not be accurately addressed through Wright’s literary portrayal of Bigger. Native Son rather than empowering Black culture and progressing the already bad image that they had in society, instead incited and stirred up its white audience, verifying to them that the Black race was inferior. It perpetuated the same stereotype and tone of violence that Black men like Bigger were subjected to their whole lives and did not give Black people and even Black authors like Baldwin much room to grow and prove society and white America wrong about their preconceptions. Because Wright failed to humanize Bigger and defined him as a reactionary experimental figure that only operated on suffering and violence, the predominantly white audience of the novel who then shared that message with America were unable to understand and view Bigger as a realized individual. According to Howe, this negative portrayal communicated “that only through struggle could men with black skins, and for that matter, all the oppressed of the world, achieve their humanity.” As a result of Native Son, deepened racial divides, completely missing the mark of what Wright claimed it was not supposed to do.

This exemplified to me how much literature can take responsibility for either deepening or diminishing societal issues like racism and racial inequality. As someone who studies Sociology, I acknowledge that there are a multitude of factors that contribute to societal problems but I never really imagined literature as having as much of an impact on shaping social narratives and perceptions in the way that Native Son did. Now, I am eager to read and find out how James Baldwin will use his literature to portray Negro men and Black culture. Although Howe stated that “Baldwin has not yet succeeded in composing the kind of novel he counterpoised to the work of Richard Wright” I am curious to see myself how Baldwin will counter the work of Wright in his own writings. Unlike Native Son, I hope that Baldwin’s work gives Black America the recognition it deserves and advances the image of Black men, Black women, and Blackness in general.

Self-Hatred in Go Tell It on the Mountain

Self-hatred is one of the most complex depths of human emotion, and as someone who has truthfully struggled with it, I am inevitably drawn to its themes when it is expressed in art and literature. Needless to say, I was surprised by the degree of self-hatred over race in Wright’s Native Son. My own ignorance towards self-hatred in the Black community was exposed once again after beginning Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain and subsequent analysis by Douglas Field in Pentecostalism and all that Jazz.

I expected the majority of struggles and self-hatred to come from John Grimes in Go Tell It on the Mountain, and while John shows a good deal of conflict over his “hardened heart”, I was drawn more to the character of John’s father. John’s struggles with religion are familiar to me, particularly with “his sin was the hardheartedness to which he resisted God’s power” (Baldwin, 17). John sees himself with darkness, an allusion to his skin and his soul, in regards to how averse he is to religion. Breaking the expectation of his Pentecostal family and community result in self-hatred. That much seems universal, at least in my eyes; expectations and pressures, particularly for young people, can put them at odds with who they actually are. That schism leads to self-hatred, and that much is one of the most common lines of humanity.

However, Baldwin seems to deal, at least in the first part of Go Tell It on the Mountain, with how self-hatred is passed down by means of the father. This is unclear at first, but is gradually revealed by Aunt Florence via her interactions with John’s father. Aunt Florence reference’s the father’s past actions to being very similar to Roy’s recklessness and states “you was born wild, and you’s going to die wild. But ain’t no use to try to take the whole world with you. You can’t change nothing, Gabriel” (47). The father’s (Gabriel) behavior is not becoming of a preacher or a holy man, and by portraying him as such, his personal life aside, Baldwin shows a pattern of repression and self-hatred in religious figures. The father beats the son that is like him and blames the one who isn’t. Baldwin also shows this another religious figure, Elisha, who after being publicly reprimanded by his own uncle for showing interest in a woman, doesn’t accept his own feelings and blames Satan for causing them. These themes are not uncommon regarding religion or fathers for that matter, but a line in Field’s essay made me especially curious: “[Baldwin] lambasted the black church’s inability or unwillingness to counter a deeply embedded black self-loathing”. Field credits Clarence Hardy’s treatment of Baldwin for the quote.

I am genuinely curious to study the differences in the Black and White community over the role the church plays in happiness, fulfillment, and self-hatred. Baldwin portrays a service as incredibly passionate, emotional, and devout, while maintaining a character who is unenthralled by the display. What role does the church play in a “deeply embedded black self-loathing” and how prevalent is self-hatred in the Black community compared to others?

Baldwin’s Religion

Douglas Field’s Pentecostalism and All That Jazz: Tracing James Baldwin’s Religion is probably one of my favorite articles that we’ve read so far. I appreciated how this article made sense of Baldwin’s understanding of religion and it allowed me to think about how growing up in the Baptist Church has affected my perspective of religion. I agreed with Baldwin’s argument of how the church as an institution can be contradictory and produce a lack of self love. I’ve seen how the Baptist church can condemn its members and I’ve seen how the Baptist church can be a safe haven. The point that I resonated with the most is that you can be critical of the church and still be very Christian or religious. I also appreciated the history lesson on jazz music and the Pentecostal church. I think that being involved with music in any aspect can be religious or spiritual. I also never thought about how religion can lead to passivity and I think Field makes a great point when he states, “Baldwin suggests that piety not only leads to passivity, but that it damages personal relationships” (446). I feel as though this happens with a lot of religious people who blame their actions on God instead of taking responsibility for it. Further it is often people who claim to be the most Christian that I’ve seen do this. It also turns people away from faith in anything when people of the church continuously act hypocritically. Baldwin’s practice of an anti-institutional spiritually shifted my interpretation of part one of Go Tell It on The Mountain. I didn’t think that this novel was going to be critical of the church. I knew that religion was going to be a theme in the novel but I didn’t think the criticization of the church was going to be a central point of chapter one. I am curious to see how Roy’s and John’s paths diverge or connect throughout the rest of the novel.

Field also addresses Baldwin’s ideology of salvation through the love and support of one another. He states, “Baldwin’s most radical rewriting of Christian–or at least spiritual identity–is to place emphasis on salvation and redemption, not through God, but through a love that is founded on the sharing of pain” (450). Can we be saved through each other? If God is the ultimate judge, do humans have the agency to save each other in a religious sense? I am not sure if Field meant for this to be taken quite literally. However, I am taking Jesus and Salvation for my second theo requirement right now so that could also be a reason why I am reading so deeply into this statement. The purpose of this article is to address Baldwin’s opposition to the church. However, I did not expect his interpretation of his use of religious language in his writing to be taboo. He states, “In Baldwin’s later fiction, nakedness is holy, but the fear of judgment is replaced by the act of complete surrender to another lover. This authentic sexual love becomes itself an act of both revelation and of redemption” (452). Baldwin’s idea of a holy sort of love is what we would associate as traditionally taboo, which makes his work all the more thought provoking to me. Field is quick to acknowledge that Baldwin is not talking about sexual gratification, but more of a spiritual sexual love that is received by both people involved. I have seen If Beale Street Could Talk and I think the movie captured this aspect of a spiritual love. I loved how the article ended by reiterating that “Love, then aided and nurtured through gospel music, becomes the bedrock of Baldwin’s new religion. Irrespective of class, gender or sexuality, love becomes, for Baldwin, a redemptive act” (453). Further, “Love, spiritual love, is the new religion. For it is ‘love’, Baldwin concludes, ‘which is salvation.’” I think Baldwin’s understanding of religion is digestible, coming from the perspective of someone who is a Baptist Christian and his philosophy makes a lot of sense to me.

Being a ‘mixed’ today… inspired by past readings

In Native Son, we see how the self-identification of Bigger affected him and his whole life, how the self-hatred form inside of oneself can turn into something sinister. This relays a different perspective from the Moon & Mars. This book is about a little girl who just sees her family. She is the first to be born out of slavery and the center of attention. The book (at least the parts I read) shows the importance of family and honoring differences, not just similarities. That being said, It is not to be said that it is easy. After meeting with the author of the book I felt a lot of things. I felt a relation to her. Being mixed, in a time like that could not have been easy. Being mixed in today’s world is not the easiest thing.

In a society where labeling has become the most important thing, being mixed is not easy. I feel it almost every day. I am currently filling out job descriptions and every time I do, I check the box that says ‘two or more races’. That box, makes me think about what it truly means to be mixed in a world that for so long wanted to keep things separated. It makes me think about the earlier article we read in which, we talked about choosing to be white when people first moved to the U.S. They did not do this for no reason at all, they did it to survive. The U.S. was a place in which being white was the main factor of survival. It was a way to be able to survive in a place where people who ‘different’ were outcasted.

For me, growing up mixed has been an interesting thing. From high school, I have been going PWIs without a second thought. I have been told I am too white and I have been told that I am too black. Yet, for some reason, I have always just felt like I am me. There are fronts I put up of course, for reasons that are not just due to race, but in a world where everyone has to be labeled as something, where does that leave the people who are more than just one identity? For me personally, it has left me in a place of slowly, but surely making my own identity that has always excluded race. I am an athlete, granddaughter, sister, daughter, friend… Yet, in a world where it is so hard to include yourself when you are born in a place where you never quite fit in, how do you find your identity any other way?

Native Son as Everybody’s Protest Novel

“How Bigger Was Born” is Wright’s attempt to explain to the reader his motives for writing such a gruesome novel. It is hard to believe that the world he creates for Bigger is respectable. His childhood serves as the main factor into his perspective on the experience of black men in America. He claims that he knew several “Biggers” and the one in Native Son is an accumulation of the black men that he watched meet unfortunate endings. In trying to understand his reasons for writing Native Son, he fails to convince me that writing it was “an exciting, enthralling, and even a romantic experience” (461). He argues that black men being accused of rape is “a representative symbol of the Negro’s uncertain position in America” (455). I find this claim to be flawed because Bigger did rape Bessie and wasn’t even charged for rape in the novel. Further, he states that after writing Native Son he started another novel on the status of women in modern America. Wright’s focus on this aspect of the criminalization of black men is concerning, when he claims that he wrote the novel to free himself from a sense of shame and fear that comes from being black in America. In the end Bigger is not really freed from this sense of shame and hate. He buried it under the euphoria he experienced from murder. One of the most striking arguments he presents is that he “was fascinated by the similarity of the emotional tensions of Bigger in America and Bigger in Nazi Germany and Bigger in old Russia. All Bigger Thomases, white and black, felt tense, afraid, nervous, hysterical, and restless” (446). This comparison took me away from the Bigger portrayed in the novel as a person and led me to looking at Bigger as an idea apart from race; a dangerous one. He states, “The difference between Bigger’s tensity and the German variety is that Bigger’s, due to America’s educational restrictions on the bulk of her Negro population, is in a nascent state, not yet articulate. And the difference between Bigger’s longing for self-identification and the Russian principle of self-determination is that Bigger’s, due to the effects of American oppression, which has not allowed for the forming of deep ideas of solidarity among Negroes, is still in a state of individual anger and hatred. Here, I felt, was drama! Who will be the first to touch off these Bigger Thomases in America, white and black?” (447). How is the reader supposed to believe that Bigger is merely a product of his environment when his persona is based on extreme ideals. I am still trying to figure out where I stand with this book and “Everybody’s Protest Novel” brings a little clarity. Baldwin states, “For Bigger’s tragedy is not that he is cold or black or hungry, not even that he is American, black; but that he has accepted a theology that denies him life, that he admits the possibility of his being subhuman and feels constrained, therefore, to battle for his humanity according to those brutal criteria bequeathed him at his birth” (18). Further, “The failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being…” (18). Native Son is a life-draining novel and reflects the depressing state of the war stricken world during the time it was written in.

Character and Intent in Native Son

Wright’s How Bigger Was Born section of Native Son is remarkably in line with a good amount of the critiques brought up in class and in previous reflections. I was particularly interested to see if Wright would address or anticipate some of those critiques. He does, and in doing so, Wright revealed what I think is a very prevalent theme in how Native Son is presented.

Wright completely dismisses any opinion contrary to his own. Several sections of How Bigger Was Born were particularly striking, namely “I felt with all of my being that he was more important than what any person, white or black, would say or try to make of him” (450). That is Wright’s only addressal of the complaint that he paints a bleak picture of Black identity. That is a woefully inadequate position, because Wright seems to be dismissing the very experience of the reader, which is, in basic terms, the point of writing a character. “They did not want people, especially white people, to think that their lives were so much as touched by anything so dark and brutal as Bigger” (449-450) is another claim Wright makes about issues the Black community might have with Native Son. But he doesn’t go any further. Wright makes no claim and records no thought about what effect that might have on the reader. Which, once again, is the purpose of writing a book. Telling a story that affects a reader, whether purposefully or not. I think that is why Native Son seems somewhat inconclusive as well. Several of us in class asked the question: so what? Where do we go from here? What’s the point of portraying Bigger this way? Wright explains how but not why, which leads the story and the explanation to seem somewhat inadequate. Wright also completely dismisses any notion of Black pride or culture with the simple line, “Still others projected their hurts and longings into more naive and mundane forms–blues, jazz, swing–and, without intellectual guidance, tried to build up a compensatory nourishment for themselves” (439). Once again, Wright offers no clarification as to why this is bad, why such forms are “naive”, or why Bigger’s lens on Black America is more apt. Finally, Wright makes not a single reference to the role of women in Bigger’s life. The seldom times he mentions rape, which is a massive part of Native Son, he solely discusses rape in the context of its connotations for Black men, which are undoubtedly present, but is entirely dismissive of women. This explanation reaffirms conclusions about Native Son: Wright focuses the story with an incredibly narrow lens, that not only highlights a very particular approach to Blackness, but also dismisses any other approach to those topics.

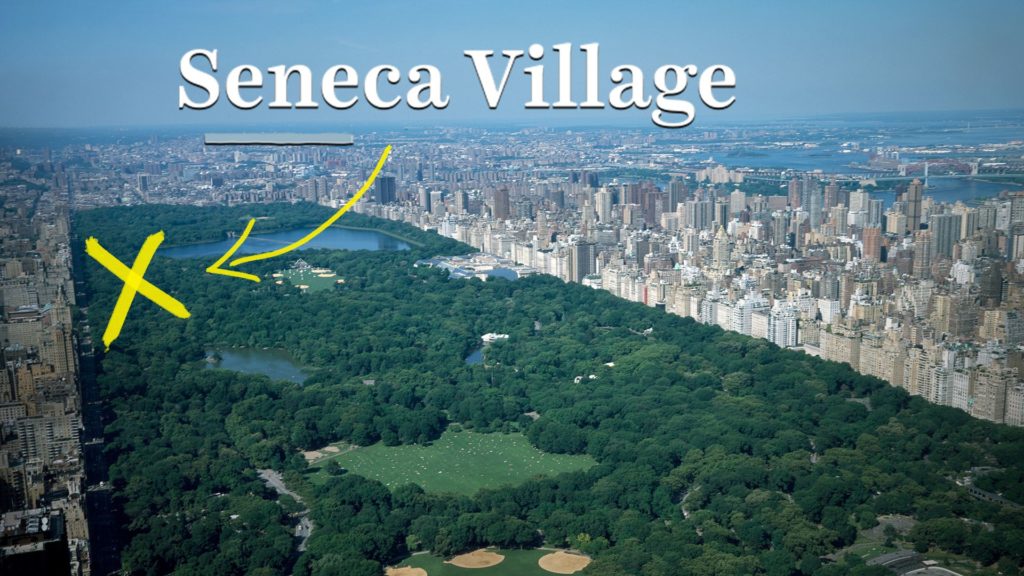

Central Park and the Spatiality of Race

A few months ago I visited New York City for the first time. Prior to my arrival, my friends, temporary residents of Manhattan for the duration of their summer internships, asked me what places I would most like to visit. At the top of my list stood “✰Central Park✰,” underlined and starred as such to clearly convey to them this was a “must do.” I am happy to say that we walked, what felt like, the entirety of Central Park. I was in awe at the sight of this place that I had only read about in books and seen in movies and TV shows.

However after reading an excerpt from Kia Corthron’s Moon and the Mars, I realized that I had in fact not seen Central Park in its entirety as I had first thought, and even more so, nor would I ever be able to. As the book explains and as was further discussed by Corthron herself in class on Wednesday, Central Park as we know it today keeps buried a dark secret beneath its long stretches of green grass. The tourist attraction actually arose from the destruction of Seneca Village, home to quite a few of Theo’s family members in the book. The New York Times reported that in the debate over where to place Cental Park uptown landowners and newspapers used racial slurs to paint Seneca Village as “a shantytown at risk of becoming the next Five Points,” another site in the book where Theo spends most of her time. Upon learning this, I was shocked– how could an event of this magnitude be completely lost in time? I argue that this question is tragically rather easy to answer. This is because Seneca Village, like Five Points, was a poor community that primarily consisted of Black people and Irish immigrants. It was not only a mindless choice to demolish this neighborhood but also to wipe it from history exactly because of who it was that occupied this space; to the wealthy Whites of Manhattan, Seneca Village’s occupants and their homes and livelihoods did not matter. Furthermore, despite the poverty and unstable living and working conditions Theo and her loved ones faced in both of these neighborhoods, these spaces provided its residents a form of protective relief from the racial discrimination they experienced in other parts of the city. Thus, the neighborhood was completely razed to the ground, and with it, a community, culture, economy, and network of people erased from history. With that being said, in focusing on these forgotten neighborhoods of New York City, Corthron’s novel highlights the racialization of space in determining who and where has value and who and where is disposable.