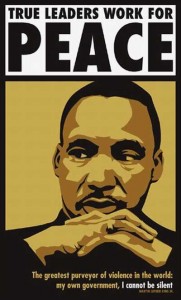

As another Martin Luther King, Jr. Day approaches, MSPS reflects on the dream at Notre Dame.

The other night I heard a community organizer from South Bend speak. They call him Brother Sage, a name he earned while serving as principal for a failing elementary school in East St. Louis, as he says “a neighborhood where kids wake up in the morning and gargle razor-water.”

Brother Sage recalled his teenage years in 1964, when a barber in his hometown in Ohio refused to cut the hair of African Americans. Yet, in the same breath, Brother Sage called for striving for peace among all communities.

I asked, “How do you attain peace? How can you build trust with the barber, or a community other than your own, that doesn’t share your beliefs?”

He replied, “Go outside your comfort-zone.”

What I really wanted him to tell me was, “well, it’s ABC…” but the truth is that there are no guidelines to overcoming the bitterness of bigotry. There are no guidelines for creating for a just society. There is no single way to engage with others who may not share your perspective, or may in fact, staunchly oppose it.

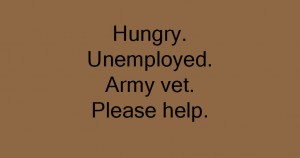

The reality is that individuals who agree with the barber in Ohio still exist.

The reality is that those elementary students who attended Brother Sage’s School were born into low-income housing, born into a system that secludes them from access to an equitable education, born into a generational cycle of poverty.

Desegregation and equal access to education – these are two of the issues that Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life for but they are still prevalent today. How can we work towards making Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream for freedom and justice a reality?

Like Brother Sage said, one way to strive for peace is getting comfortable with being a little uncomfortable.

“As we walk, we must make the pledge

that we shall march ahead.

We cannot turn back.” – MLK