June 21, 2015 |

Let the hate crime investigations begin in South Carolina, though some say it’s not needed; they’ll push for the death penalty regardless.

But I say, if hate is present, we should acknowledge it, if we care about the truth. The hate crime route is worth it. It’s just not an easy journey.

Asian Americans know all too well about the politics of pressing for justice in a hate crime case.

We’re still mourning Vincent Chin, who died 33 years ago June 23, four days after being brutally beaten with a baseball bat.

The incident started June 19, 1982. Ronald Ebens, then a 42-year-old White Chrysler autoworker, alongside his stepson accomplice Michael Nitz, 23, took a baseball bat and bludgeoned Chin, a 27-year-old Chinese American, to death on Woodward Avenue in Highland Park, a suburb of Detroit.

Initially, all three were in a strip bar, the Fancy Pants.

Chin was at his bachelor party, soon to be married.

Ebens and Nitz were having drinks after work.

There was an argument in the club between Chin and Ebens that was taken outside to the street. It should have ended there. All parties left, but then Ebens and Nitz pursed Chin and tracked him by car at a nearby McDonald’s.

The killing happened in the fast-food parking lot.

Some witnesses say Nitz held down Chin. Some say he didn’t. Everyone says he was there and did nothing to stop Ebens, who ferociously struck and beat Chin repeatedly with a baseball bat. Two savage blows to the head left Chin unconscious. He died later in an area hospital.

For their admitted role in Chin’s death, here’s the amount of time Ebens and Nitz served for the crime they committed: zero.

Ebens and Nitz were allowed to plea bargain in a Michigan court to escape mandatory jail time for second degree murder. Ebens pleaded guilty; Nitz pleaded nolo contendere. Both men got this sentence: three years’ probation, a $3,000 fine, and $780 in court costs.

It never fails to make any crowd gasp in disbelief.

The light sentence set off such a response that a second trial, on civil rights charges in federal district court, was inevitable. But it was an angry, strident affair with a conclusion to match. Nitz was acquitted, but Ebens was convicted to 25 years in prison.

Hooray? Not quite.

Ebens always called the federal trial a “frame-up” and appealed for a new trial to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. That court saw the failure to change venues and the coaching of witnesses by a community activist as reason enough for a new trial.

At that point, the new case was put in Cincinnati, Ohio, far removed from Detroit, the Michigan media, the auto industry, and five years after the night of the attack.

It was advantage Ebens, who on May 2, 1987 was found not guilty on the federal civil rights charges.

Ebens told me in a conversation three years ago that the whole matter wasn’t about race. It wasn’t that the autoworker thought Chin, a Chinese American, was Japanese and therefore a symbol of the Asian auto industry.

Ebens said that wasn’t it at all. He said he was sucker-punched by Chin.

Maybe. But to me the crime was clear. If Chin were not Asian or a person of color, I think Ebens wouldn’t have felt the rage he did nor would he have extended the fight beyond the Fancy Pants into the street and then later to the McDonald’s. Ebens beating another White guy? He would have seen himself. Not some “other.” He would have stopped short of homicide. But he didn’t.

There was enough hate present in my legal system to give him the hate crime enhancement to ensure time was served.

But we’re past that now. Whether Ebens says it was or wasn’t about race is kind of irrelevant anyway. The facts are the same: Ebens killed an Asian American man. And got away with it. To this day, he continues to claim poverty to avoid the huge wrongful death judgment against him.

The system still works for Ebens a lot better than it does for any of us.

Let’s hope it works better in Charleston.

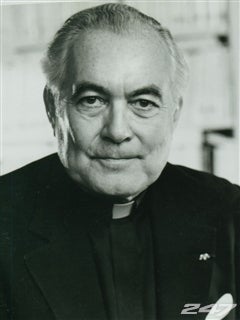

Emil Guillermo is an award-winning journalist and commentator who writes for the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund. Contact him at www.amok.com; www.twitter.com/emilamok , www.fb.com/emilguillermomedi