Marvin Worthy’s charge to the new resident hall staffs on Wednesday afternoon was to stand up and to be a leader in the fight against oppression on campus this year.

Marvin Worthy’s charge to the new resident hall staffs on Wednesday afternoon was to stand up and to be a leader in the fight against oppression on campus this year.

That’s a fairly tall order and I’m not as good at inspirational speech as Mr. Worthy.

The truth is there’s a lot to unpack following an afternoon devoted to diversity and oppression, and Mr. Worthy’s charge to stand up—echoed by MSPS—isn’t an easy thing.

It isn’t an easy thing to do: to change a campus culture, to fight oppression on a campus steeped in many years of tradition.

Because tradition, by design, operates counter to change.

And to fight to change will occasionally or always mean defying and dismantling quite a bit of what’s considered tradition.

Are you prepared truly and wholly to do that?

–I have worked in Multicultural Student Programs and Services for five years and I’m still not 100% sure that I can do it 100% of the time.–

(And if you’d like to talk to me about that process, I am always willing.)

Mr. Worthy suggested yesterday that to fight oppression will be difficult, but that “we have to try.”

But I wonder if that’s totally true. We don’t have to try, do we?—not if we don’t want to.

Sure, we can and should respond to negative, discriminatory acts on our campus–acts which we recognize are not isolated incidents, but rather daily occurrences and which are inherent in our world and on our campus.

But that doesn’t mean we have to challenge ourselves to understand these acts on a deeper level. We don’t have to critique our traditions and to work together to fight the oppressive systems that allowed these acts to happen in the first place.

We don’t have to—not if we don’t want to.

It is insufficient to understand our leadership roles as those of doctors and nurses in a hospital treating all patients regardless of their afflictions and regardless of their racial, sexual, gender, class, or religious orientations and identities.

It is insufficient because to tolerate difference—as if difference is something undesirable that we must nevertheless deal with—is to deny the true identity of others on an equal and socially just plane.

Does this make sense?

From the activist Audre Lorde:

“Advocating the mere tolerance of difference… is the grossest reformism. It is a total denial of the creative function of difference in our lives. Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic. Only then does the necessity for interdependency become unthreatening. Only within that interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no charters.”

(The larger original is worth reading several times, as well, if you’re interested.)

Lorde is advocating that merely tolerance and acceptance of difference is insufficient.

Rather than tolerance and acceptance of differences, we need to be motivated to acknowledge differences as wholly and intrinsically equal.

If we were motivated to view differences as wholly and intrinsically equal in value, then differences could not be demeaned as the butts of jokes or the objects of insensitive parties or the underlying motivations for hate mail, hate crimes, and hate speech on our campus and in our daily lives.

It is absolutely an issue of social justice to work fully toward achieving a level of understanding that acknowledges that differences should be appreciated as of intrinsically equal value, not merely traits that must be “tolerated,” “accepted,” or “dealt with” passively.

It is absolutely an issue of social justice to work fully toward achieving a level of understanding that acknowledges that differences should be appreciated as of intrinsically equal value, not merely traits that must be “tolerated,” “accepted,” or “dealt with” passively.

But again, this kind of deep, structural understanding and motivation to change is difficult.

Traditions and familiar ways of doing things might have to die absolutely will have to die for true change to happen.

We’ll probably have to put turf on the football field, too.

And that is because we understand today that there are better ways to do things than before. And that’s OK. And that’s necessary for the survival of our world.

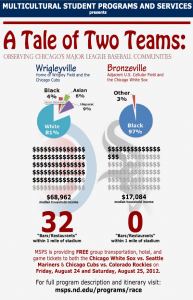

Mr. Worthy rightly suggested that his presentation should not be the end, but the beginning of the conversation. There will be several opportunities to continue to engage with issues of race and identity and class this year through the offerings of MSPS and other sharp, like-minded, action-oriented departments and offices.

Be sure to check those out.

Of course, you don’t really have to—not if you don’t want to.

But like Mr. Worthy, MSPS is calling on you to stand up and do it because you want to and because it’s Right.