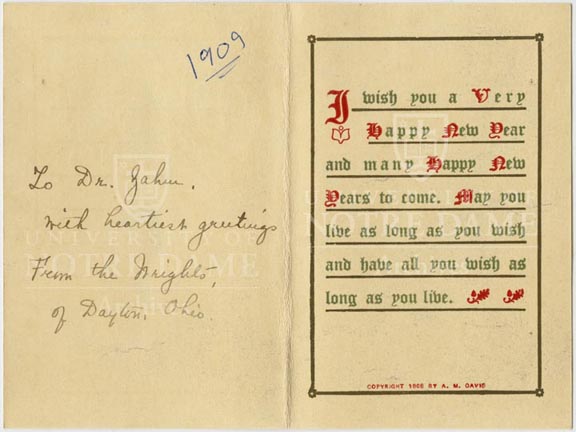

Frank C. Walker entered the Notre Dame Law School in 1906 and began an affiliation with the school which lasted throughout his life. He graduated in 1909 and later served on the University’s Board of Lay Trustees, worked for the Notre Dame Foundation, and was a member of the Notre Dame Club of New York. He was given an honorary degree in 1934 and the University’s Laetare Medal in 1948.

He supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s campaigns for governor in 1928 and the presidency in 1932. During the 1932 campaign he served as Treasurer of the Democratic National Committee. President Roosevelt appointed him executive secretary of his President’s Executive Council in 1933, and he subsequently acted as executive director of the National Emergency Council.

Post Master General Frank C. Walker, Notre Dame Law School Class of 1909, and Miss Helen Richards of Hazelton, Pennsylvania (PA) work the USO-NCCS overseas Christmas Mailing Booth, National Catholic Community Service, Washington, D.C., c1943

Post Master General Frank C. Walker, Notre Dame Law School Class of 1909, and Miss Helen Richards of Hazelton, Pennsylvania (PA) work the USO-NCCS overseas Christmas Mailing Booth, National Catholic Community Service, Washington, D.C., c1943

In 1940 he was appointed to succeed Jim Farley as Postmaster General of the United States, in which position he served until 1945. In 1946 he was appointed by President Truman as alternate delegate to the first United Nations General Assembly session in London. He returned to his business interests in N.Y. as director of W. R. Grace & Co. and the Grace National Bank of New York.

The Papers of Frank C. Walker document his life from his early days in Butte, Montana to his tenure as Postmaster General during World War II. Walker’s career in national politics was the result of his long friendship with Franklin Roosevelt. Much of the collection consists of office files from his service in the Roosevelt administrations, first as head of the Executive Council and the National Emergency Council and then as Postmaster General. It was also at Roosevelt’s behest that Walker served as Democratic Party treasurer and chairman of the Democratic National Committee. It was loyalty to Roosevelt, rather than personal ambition, that kept Walker in public service.

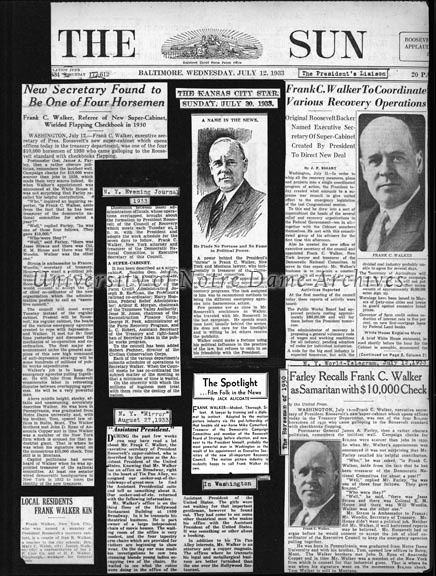

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook, c1933

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook, c1933

Most of Walker’s papers are from the positions he held within the New Deal and the Democratic Party. The Roosevelt campaigns, the formulation of New Deal programs, the selection of Harry Truman as vice-president in 1944, and other political events of the 1930s and 1940s are all discussed in Walker’s Papers and have been of most interest to historians. But the collection also documents Walker’s early career as a lawyer in Butte, his work as general counsel and president of his family’s theatre business, and his personal interests in the University of Notre Dame and Catholic charities. These parts of his life are not represented by the extensive office files that document his days in public service, but it is clear from the Walker papers that his life included much more than politics and government service.

A good source for information on all aspects of Walker’s life are the memoirs he worked on during his retirement but never completed. The transcripts, drafts, and notes that he produced as part of the project fill in many of the gaps in his papers. This is particularly true of his college days, the time he spent as a trial lawyer in Butte, and his work with the Comerford theater business. His recollections of Roosevelt, New Deal programs and personalities, and the politics of the period offer a personal point of view that is missing from the more public office files he accumulated. The memoirs tell us much about Walker, who despite his many years in public life was still a very private man.

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook with newspaper clippings regarding his Laetare Medal, installation of Archbishop Spellman, and United States delegates at the UNO Assembly, c1939-1949

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook with newspaper clippings regarding his Laetare Medal, installation of Archbishop Spellman, and United States delegates at the UNO Assembly, c1939-1949

Frank C. Walker donated his papers to the Archives of the University of Notre Dame in 1948, although the entire collection was not transferred at that time. After his death in 1959 the Walker family gave additional material to complete the donation. Walker’s books, photographs, and record albums have been taken from his papers to form separate collections, each with its own finding aid. His books cover a wide variety of topics, although politics and the New Deal dominate. The photographs are largely from his tenure in government service, particularly with the Post Office; they include portraits of Walker with many of the political figures of the 1930s and 1940s. The record albums that came with the Walker Papers include a few of his speeches. In 1990 an oral history was conducted with Thomas J. Walker and Laura Walker Jenkins, Frank Walker’s son and daughter. The transcript and tapes from this interview are also available.

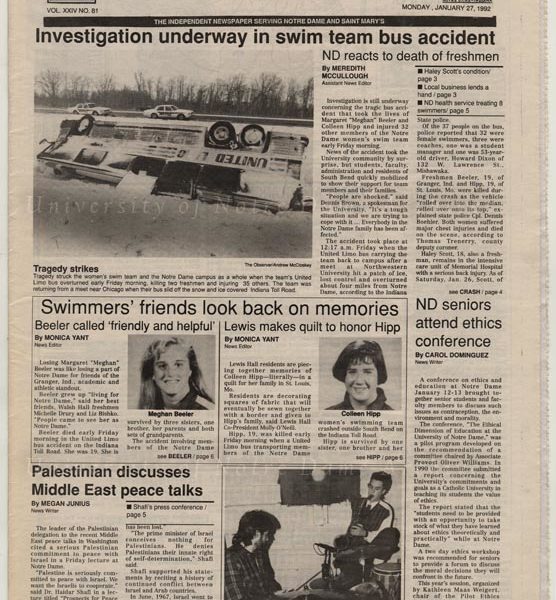

Front page of the 01/27/1922 issue of The Observer

Front page of the 01/27/1922 issue of The Observer

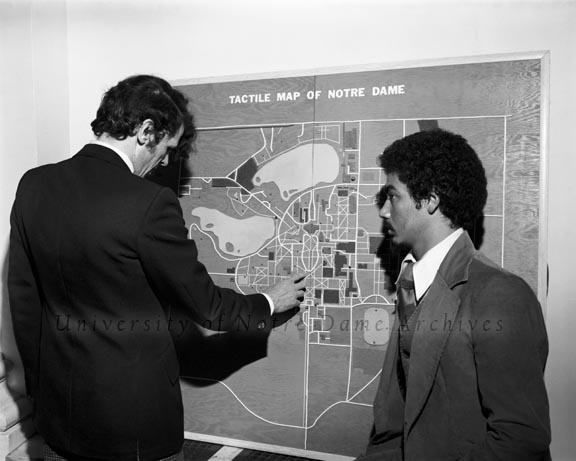

Dr. Stephen J. Rogers Jr. explores a textured campus map as Architecture student Leroy Courseault, who designed and constructed the map, looks on, 1978/0515

Dr. Stephen J. Rogers Jr. explores a textured campus map as Architecture student Leroy Courseault, who designed and constructed the map, looks on, 1978/0515

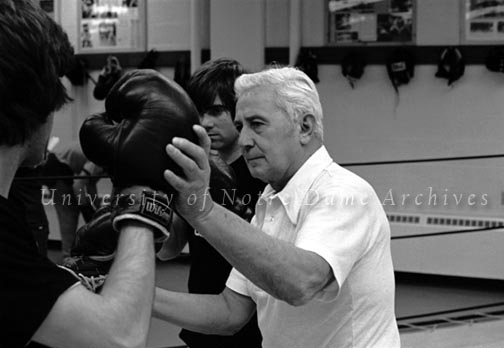

Hockey Coach Charles “Lefty” Smith, c1970s

Hockey Coach Charles “Lefty” Smith, c1970s Hockey Coach Charles “Lefty” Smith teaching techniques to a group of boys on the ice during a youth sports camp, 1978/0720

Hockey Coach Charles “Lefty” Smith teaching techniques to a group of boys on the ice during a youth sports camp, 1978/0720

Scholastic, December 28, 1867

Scholastic, December 28, 1867

Post Master General Frank C. Walker, Notre Dame Law School Class of 1909, and Miss Helen Richards of Hazelton, Pennsylvania (PA) work the USO-NCCS overseas Christmas Mailing Booth, National Catholic Community Service, Washington, D.C., c1943

Post Master General Frank C. Walker, Notre Dame Law School Class of 1909, and Miss Helen Richards of Hazelton, Pennsylvania (PA) work the USO-NCCS overseas Christmas Mailing Booth, National Catholic Community Service, Washington, D.C., c1943 A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook, c1933

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook, c1933 A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook with newspaper clippings regarding his Laetare Medal, installation of Archbishop Spellman, and United States delegates at the UNO Assembly, c1939-1949

A full page from a Frank Walker scrapbook with newspaper clippings regarding his Laetare Medal, installation of Archbishop Spellman, and United States delegates at the UNO Assembly, c1939-1949