Chapter Overview:

The development of the physiology of the head is discussed in this chapter. Roberts uses evidence from embryonic development and our relatives to describe a narrative of how our head developed to look the way it does and the unique physiology of its sense organs.

Chapter Summary:

Roberts begins her discussion with a description of the neural crest, how it forms and how it will later be vital to the formation of the skull and many other important structures. She discusses the investigation of the evolution of neural crest cell genetics by looking at lancets and jawless fish, which are a closer relative to lancets but do possess neural crest cells during development. The difference, she explains, lies in large scale duplications of Hox genes which can then evolve to fulfill new functions, as is the case in vertebrates which have several copies of a particular Hox gene which is vital to the activation of neural crest cells in developing vertebrate embryos. She also talks about the role that neural crest cells can play after migrating, including having a vital role in the formation of the skull, an idea that was widely disbelieved until better methodology developed to prove that this was indeed the case.

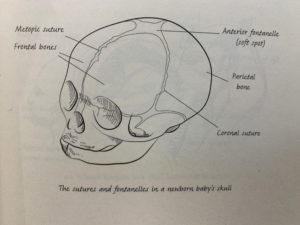

Although the adult skulls of humans may look very different than those of other animals, in our infancy we have many similar structures that make our relationship easily identifiable. The malleability of the infant skull is very useful because it allows for expansion of the skull with growth of the brain. Culturally, this malleability has been taken advantage of culturally in many societies to form the skull by manipulation to socially desirable shapes. Cultural manipulation of the skull is not associated with impeding the brain from developing, but early closure of sutures can cause deformation of the brain.

Roberts starts a discussion of the general anatomy of skulls with the differences between male and female skulls, males usually having more robust features and women usually having a more gracile skull. She then discusses how remains can be aged using the sequence of teeth maturity or more roughly, suture closure in the skull and tooth wear. She then describes the general anatomy of the auditory system and how it transforms sound waves into nervous impulses. She discusses the olfactory system in mammals and the evolutionary degeneration of primates’ olfactory system compared to other mammals who are much more sensitive to smell. One theory is that this disinvestment came with a stronger reliance on vision. She discusses the seemingly impossible development of the eye. She describes that indeed the beginning of this complex structure probably was more like a photosensitive cone that developed later into more controlled and complex structures that we now use in our eyes. She proposes how the ability to sense light may have been advantageous in free swimming animas even before it allowed sight as we experience it today. Eventually this led to the development of eyes as we know them. Even a structure as complicated as the eyes can be reasonably interpreted in light of our developmental and evolutionary history.

Next, she discusses the history of color vision in mammals. In jawed fish, there are four different cones, allowing them to see in color. However, in most mammals, we see that there are only two, not allowing color vision. Only primates have regained this ability through evolution. Roberts proposes that this history points to a nocturnal ancestor that did not need color vision to see in the dark, then points to our recent history of fruit eating or predator spotting as a reason we may have regained this ability. She also discusses the placement of primate eyes, why ours are located where they are and how this is helpful for stereoscopic vision. She also talks about the large sclera of humans, which allows us to see where each other are looking in contrast with other animals which show little or no sclera. This is related to our social nature and brain development. Our ability to infer what each other think is very important for our sociality. She also discusses the physiology of the eye and the logical shortcomings that evolution has filled in with elaborate processing mechanisms.