Chapter Overview:

Roberts discusses the development of the gut during development and the evolutionary roots of our modern gut physiology as well as whether it is unique or standard for a primate of our size and diet.

Chapter Summary:

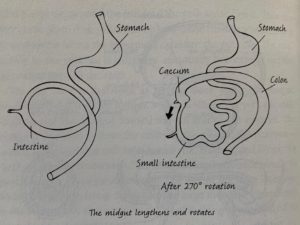

Guts all originate in the same way, as a simple tube of endoderm. Human embryos have a yolk sack, a reminder of our close relation to other animals who lay eggs. The yolk sac in humans is not useful as embryos and fetuses get their nutrients from their mother and it degenerates by the time of birth. The development of the gut starts simply but the tube convolutes and specializes depending on region to create the entire gut from the mouth to the anus. The gut grows so quickly that the abdomen does not have time to keep up and the gut must herniate into the umbilical cord. This resolves as the fetus develops and the gut usually returns to the inside of the abdomen. In fact, this herniation creates the organization we have in our adult gut.

Roberts describes her own experience of having an exploratory procedure of her small intestine. Her reflections of the experience of having a small “pillcam” photograph her intestine describe how modern imaging techniques allow us to visualize areas of the body we would not be able to otherwise.

The human gut is rather standard as far as primates’ intestines go. Ours guts are unspecialized; they are capable of digesting a wide variety of food sources. Human guts are small for our body size. This may be because the gut is very energetically expensive. As the brain expanded, our gut may have contracted. This is thought to be a product of the ability of our brain to find high quality food which mandates less surface area to extract sufficient nutrients. Theories propose that the expansion of our brains and the beginning of food processing, the gut became shorter. Roberts denies the importance of these differences, suggesting that we really do have very standard primate digestive systems and that in the past we were too intent on identifying parts of ourselves that are unique.