Chapter Overview:

Roberts discusses the reproductive systems of humans and our closest relatives to explore the somewhat unique features and challenges of human reproduction.

Chapter Summary:

This chapter is a survey of the human reproductive system. It begins with a description of the goal of the reproductive system, to unite a sperm and egg and to form a new human. Transferring from water to land was a challenge for reproduction. Most fish release their eggs then another fish releases its sperm above the nest to fertilize them. Land animals have a harder time. One way that animals have overcome this is by returning to the water to lay their eggs like frogs and other amphibians. Reptiles began to engage in the first coital transfer of gametes. A male and female reptile press their cloaca (opening for the large intestine, bladder and reproductive tracts) together and the sperm is transferred from the male into the female. The fertilized egg is then deposited by the female after developing a little. Birds and mammals are descended from this line of reproductive strategies. Most birds use a similar strategy to reptiles to transfer sperm, but a few reptiles and birds have erectile penises. Mammals have external penises which they use to introduce their sperm into their mate.

In embryos, both female and male genitals follow a similar developmental pattern. They start the same and eventually the X or Y chromosomes are activated, and the genitals will differentiate into those of the sex of the fetus. In the end, the reproductive organs of males and females look quite different, but they are made up of largely the same tissues. The evolutionary history of the testes involves a duplication of the kidneys called the mesonephrons. In humans, these structures become the Wolffian ducts and descend to the testes and become the sperm ducts of the testes and the vas deferens, connecting the reproductive tract with the urinary tract. In women, these structures do not play a part in reproductive anatomy. In females, the Mullerian ducts are dominant and become the oviducts of the female reproductive system while the Wolffian ducts disappear. One strange feature of the human female reproductive system is the presence of a single, unforked uterus which allows for us to sustain a pregnancy and have single births.

Next, Roberts discusses the migration of gonads in both females and males. In males, the gonads migrate a long distance to rest in the scrotum. In females they descend from their original position in the back of the abdominal cavity to where they will rest above the uterus. Roberts then discusses the vulnerable position of the testicles in human males. She explains that it is thought that sperm production with the least error in DNA production and with the greatest efficiency mandates lower temperatures. Finally, Roberts discusses the size of human testicles and how they compare to our closest relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas. Gorillas, though they have the largest bodies, have the smallest testicles. And chimpanzees, though they have the smallest body size possess the largest testicles. This has to do with sexual competition. In highly promiscuous species like chimps, females may have the sperm of more than one male in their reproductive tracts so having more sperm per ejaculation and higher quality sperm gives a male a higher chance of fertilizing an egg. Gorilla males do not compete with other males directly. If they have a harem of females, they have exclusive mating rights to the group. In this way they do not need as much sperm to ensure fertilization. Humans, in the middle of these extremes, have a mix of promiscuity and monogamy which is reflected in our testicles.

Roberts discusses the anatomy of the human penis and clitoris. The penises of mammals are widely varied, and the clitorises of mammals are similarly varied. The mechanisms that result in an erection in males are very similar to those that are involved with the female erection. Erections are the result of an increase in the production of cGMP in the area which causes arteries to swell and increase pressure in erectile tissues. In erectile dysfunction, the enzyme that breaks down cGMP in the genitals breaks down cGMP before it can take full effect. The drugs that correct this dysfunction in males may also be a promising lead towards helping to alleviate similar dysfunction in females.

Oxytocin is an important chemical in pair bonding as well as bonding between parents and children and is also important for biological functions including orgasm and milk letdown. The female orgasm is still not understood well, this lack of research stemming largely from cultural misrepresentations and societal ideals. In females, orgasm seems to be triggered by stimulation of the vagina and clitoris, the G-spot, if it exists, may also be important. Humans are reproductively active at all times of year. Because of our joint mobility, we can have sex in a greater variety of positions than other mammals. Sexual behavior is highly social. In many other primate species, sexual acts with members of the same or the opposite sex occur frequently and seem to serve social purposes such as reducing tension.

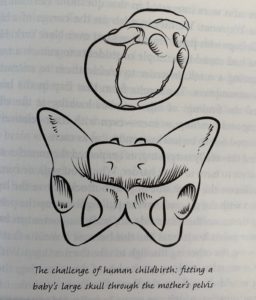

Finally, Roberts discusses difficulty birthing for humans. She explains the obstetric dilemma, the opposing pressures for cranial development and pelvic width restrictions because of walking efficiency. She then describes the faults of this theory. Metabolically, it is not more expensive for people with wider hips to walk. And furthermore, humans have very long gestational periods despite having relatively helpless youth. She proposes the energetic crisis hypothesis. This states that the mother cannot increase her metabolism quickly enough to keep up with the growth of the child, so birth occurs. Even though the birthed baby requires more energy (in the form of milk) than the gestating baby, the rate of increase slows after birth, perhaps allowing the mother to continue to keep pace with the growing young. Perhaps, she suggests, the truth is a mix of different reasons. Perhaps our cooperative birthing system has lessened the evolutionary pressure to widen hips and allowed for us to continue surviving difficult births. Whatever the truth is, surgical intervention during birthing allows for us to continue to avoid strong evolutionary pressures for wider hips and we may see these consequences exacerbated in the future because of it.