Chapter Overview:

This chapter discusses the evolution of speech and all of the structures that develop from the branchial arches, which would be gills in other animals. Roberts takes an evolutionary approach to how these structures formed and how it is reflected in our evolutionary relatives.

Chapter Summary:

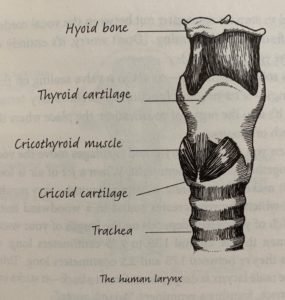

Roberts opens the chapter by discussing the physiology of modern human speech structures and how they compare to that of a Neanderthal skeleton found in Kebara. She discusses the complex structure of the larynx and the role of the hyoid bone in speech production. The larynx of humans is not unique, though. Many mammals have similar larynges. It is the structures above the hyoid that produce the specific sounds of speech. She discusses how the hypoglossal nerve tract was thought to give us an approximation of the mobility of the tongue, but later investigation found that this theory did not provide real hints about the ability to speak. It seems that ultimately, we will never know when humans developed the ability to speak, but there is evidence that Neanderthals were not as capable of making distinguishable vowels because of the length of their palate.

Roberts then discusses the myths surrounding the human larynx. It is not, in fact, perfect. She suggests that it is possible that the location of our larynx, which allows for us to speak clearly, could be a lucky accident of evolution in response to bipedalism. She suggests that if it had not descended, there would not be enough physical space in our throats for the larynx. Roberts claims that the physiological adaptations that allow for speech may not be indicative of the ability to speak at all, instead she proposes we look at the brain for hints about our use of speech.

Next, Roberts analyzes the lowered position of the adult male larynx in humans and why it may have evolved. She compares this to the voice box of male red deer, which is also much lower than the females of their species. Perhaps, like in red deer and other mammals, lower voices in human males are a product of sexual selection and sexual competition.

Roberts delves into the topic of the origin of the larynx. Surprisingly enough, it shares an evolutionary history with the gills of fish. In human embryos, structures resembling gills form and later become the larynx. She discusses the strange anatomy of the laryngeal nerve and points to its strange anatomical features as evidence of its evolution. The laryngeal nerve curves around the aorta and does a U-turn to come back up to innervate the muscles of the larynx. This is evidence of the migration of the heart in embryos and this reflects our evolutionary history.

Next there is a discussion of the ossicles of the ear and how the evolved from the duplication of the jaw hinge. Eventually these migrated and became a part of the auditory system. Roberts also adds a discussion of the evolution of human facial muscles that are useful for expressing emotions. She then describes the history of our earhole as a product of the first branchial cleft. The Eustachian tubes allow us to equalize the pressure of our inner ears and the interconnectedness of the anatomy of the head is clear in how seemingly unrelated activities such as yawning, or swallowing can open the Eustachian tubes. Our evolutionary history is better understood in light of its shared features with all sorts of animals.