Well, here we are, back at the Mothership after leaving the heat of San Antonio and the crisp walks round the lake at Wellesley. It’s wonderful to be back to the beauty of leaves falling, to be welcomed by our friends, and to feel familiar with the layout of a university campus, our American home, Shakespeare at Notre Dame.

I did a class yesterday on “Media Stardom and Celebrity Culture” with the lovely Christine Becker, and we all discussed the difference between film performances: locked eternally on celluloid, and theatre: mutable, shifting night to night with that glorious chemical reaction between audiences and cast, cast and cast, and cast and venues. Our Richard III has certainly been changing, and we’re a pretty playful bunch of actors who trust each other deeply and want to explore and mine our text to the limit. For example, in the coronation scene in Act 3 where Richard, newly crowned, tests the princely Buckingham’s loyalty by revealing deep insecurity in his position and the nuisance of having the illegitimate young princes around, I say:

Cousin, thou wert not won’t to be so dull;

Shall I be plain? I wish the bastards dead;

And I would have it suddenly performed.

What sayest thou? Speak suddenly; be brief.

Alice, who’s playing a mutely obedient Lady Anne, by my side, has started physically empathizing with Evvy’s noble and wavering Buckingham and silently pleading her horror at this thought. It gives greater emphasis to everyone else’s abhorrence of this thought and to my desire, a few moments later, to get shot of [get rid of] her and say to Catesby:

Rumour it abroad

That Anne, my wife, is very grievous sick.

Hannah who, apart from being a brilliant actor and the choreographer for various moments, had some ideas to improve the ghosts by giving them horrible unearthly gasps before each of them, all Richard’s victims, speak. It works beautifully. And Paul’s Queen Elizabeth is now so heartbreaking and vehemently reasoned in her defense of Richard marrying her daughter, that I’m having to adjust accordingly and find other tacks to succeed.

That’s the glory of Shakespeare: the endless possibilities and interpretations and the pleasure of exploring them. The reactions vary too. At Wellesley College, the audible disgust at Richard kissing Elizabeth on the mouth after persuading her to give him her daughter as a new Queen, was amazing.

Also at Wellesley, there is a Shakespeare Society (founded in 1887) that always holds a party for the actors on their first night there. The Shakespeare House (pictured on right) is INCREDIBLE: a Tudor exterior, with its own stage and a basement heaving with endless, ancient copies of Shakespeare: some with prints that I have never seen. There is a costume department worthy of a local regional theatre in Britain. One entire rail just held CLOAKS. And in November they will perform their all-female Henry V for which they have promised a video. I can’t wait.

Also at Wellesley, there is a Shakespeare Society (founded in 1887) that always holds a party for the actors on their first night there. The Shakespeare House (pictured on right) is INCREDIBLE: a Tudor exterior, with its own stage and a basement heaving with endless, ancient copies of Shakespeare: some with prints that I have never seen. There is a costume department worthy of a local regional theatre in Britain. One entire rail just held CLOAKS. And in November they will perform their all-female Henry V for which they have promised a video. I can’t wait.

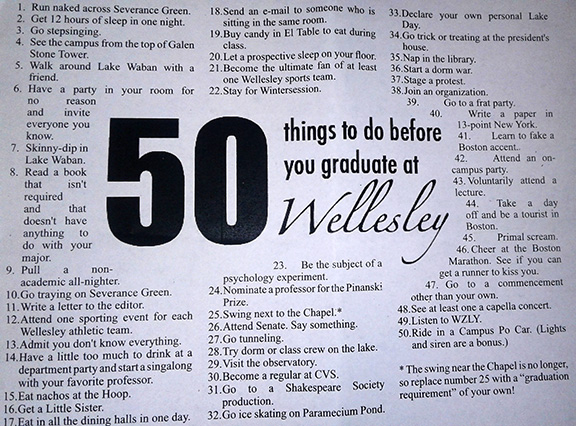

Wellesley is Hillary Clinton’s alma mater. I wonder if she ever ran naked across Severance green as is suggested on the 50 things to do before you graduate from Wellesley…I hope so.

Here at Notre Dame, we had a lovely response last night and have all had challenging and interesting classes. I worked with Peter Holland’s students on Tuesday exploring the first soliloquy and the insults to Richard. At the end Professor Holland reminded the class that, if in London, they should visit Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare, where I am a volunteer (docent in your parlance) and Trustee.

In the eighteenth century, David Garrick made his name, as a 23 year old, playing Richard III. We have a copy of Hogarth’s famous painting of him in the nightmare scene before the battle of Bosworth, as well as Garrick’s commissioned statue of Shakespeare. I was on duty there the week before we started rehearsals on Richard III and had one visitor that day who was intriguing and singular and asked the most informed questions. When I asked him if he was a historian, he said, “No, I work at Kensington Palace; I’m house manager for Richard, Duke of Gloucester.” At this point all the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. I told him I was about to play one of his boss’s antecedents and he said that the current Duke had been at the real King Richard III’s interment at Leicester Cathedral. Gosh.

Evelyn Miller puts Commedia dell’arte on its feet during a visit to John Welle’s “On Humor: Understanding Italy” class during the Notre Dame residency.

I told some of the Foundations of Theology students in Anthony Pagliarini’s class on Friday about the excellent laws that the real King Richard had passed which I learned of in Leicester Cathedral on a research visit. He ensured new laws were written in English to be understood by all. He helped confirm the place of the jury system, bail for the accused, as well as laws for land ownership and trade protection. We were discussing whether Richard’s path was chosen or determined by fate; I put forward my view that he is validating his invalidity. As Ian McKellen says in the brochure accompanying his and Richard Longcrane’s excellent Richard III film made in 1995 and set in the 1930s: “Richard’s wickedness is an outcome of other people’s disaffection with his physique.” I think that being crowned King is proof to him that he is a whole human being.

After finishing that class, I had the thrill of seeing and hearing the “pep rally”…a phrase I’d never heard before. Basically, it was all the accumulated bands of Notre Dame marching to the ground for a home game and rallying their supporters. I love a brass band. I love great big drums thumping out. And when there are over five hundred musicians playing all together, it is truly rousing.

After finishing that class, I had the thrill of seeing and hearing the “pep rally”…a phrase I’d never heard before. Basically, it was all the accumulated bands of Notre Dame marching to the ground for a home game and rallying their supporters. I love a brass band. I love great big drums thumping out. And when there are over five hundred musicians playing all together, it is truly rousing.

[Learn more about the world-famous Notre Dame Victory March.]

–Liz Crowther