Latin America and the New Evangelization

In my previous post, I considered the historical precedent in magisterial and some bishops’ writings on the New Evangelization (NE) to underscore the necessary social dimensions of sharing the Good News, that is, of evangelization. But I also highlighted a certain ambivalence about the terms and ideas of “liberation” and “social justice” in their comments about the precise relationship between evangelization and work for societal change.

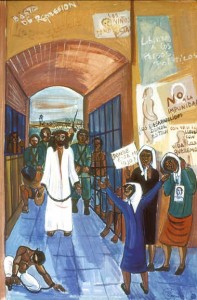

It is illuminating to explore the position of Latin American bishops and liberation theologians on the topic of the NE, since a stress on the intimate connection between the Christian faith and work for social justice and “preferential option for the poor” has become a hallmark of Latin American theology and pastoral practice. What is the contribution of Latin American bishops to the conversation about the socioeconomic aspects of evangelization? Responding to John Paul II’s call for the NE in 1992, the Latin American bishops embraced the mission of the NE and, with John Paul II, suggest that “human development” concerns can be understood as a dimension of the wider task of the NE. Yet importantly, they note the violations of human dignity associated with Christian evangelization in the Americas, for example: “With John Paul II,” they write, “we want to ask God’s pardon for this ‘unknown holocaust’ in which ‘baptized people who did not live their faith were involved.’”[1] The bishops elaborate on evangelization’s social justice dimensions and urge that the “new evangelization” not become exploitive, but rather champion the poor’s socioeconomic liberation.[2] For them, this is key if evangelization today is to be “new in its ardor, in its methods, and in its expression,” as John Paul had remarked.[3]

Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion perceptively note that the Latin American bishops generally read the term “evangelization” as “liberation” and social justice, as opposed to the U.S. bishops, who (with Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI) tend to read “evangelization” first and foremost as conversion and spiritual transformation.[4] I would also suggest that the response of the father of liberation theology, Gustavo Gutierrez, to the NE conversation is illuminating. Even more strongly than the Latin American bishops, he has underscored the importance of the social dimensions as not merely constitutive of, but the true heart of, any evangelization. Likewise, Gustavo Gutiérrez has argued in A Theology of Liberation that some past articulations of Catholic ecclesiology and missiology have actively legitimated lethal social systems, and actually violate, rather than promote, gospel imperatives.[5] In his biography of 16th century Spanish missionary to Americas, Bartolome de Las Casas, Gutiérrez recounts the awakening of Las Casas to this same conviction and defense of indigenous populations, even against the ecclesial authorities and theology of evangelization prevalent at that time.

Christian Smith interprets Gutiérrez’s work on Las Casas not as merely historical theology, but precisely as a “theological counteroffensive” to NE initiatives in Latin America, which he suggests have been wary of liberation theology’s prevalence there.[6] It is highly significant, then, that when Gutiérrez suggests the contemporary relevance of Las Casas’ life, he calls for the redefinition of “evangelization” from a liberationist perspective, not vice versa.[7] Gutiérrez writes:

Las Casas would have read with great joy …Pope John Paul II’s [writings on religious freedom]… Las Casas asks respect for the [life and] religious customs of the dwellers of the Indies and rejects the imposition of the gospel by means of power…. Here is the core of what we call today liberating evangelization. Its urgency… today has not waned since the time of… Las Casas.[8]

As we see, Gutiérrez reframes the concept of “evangelization” as one element of the liberationist project, not the reverse. It is noteworthy that in lieu of the term “new evangelization,” whether consciously or not, he calls rather for a “liberating evangelization.” Likewise, Leonardo Boff has noted that any “evangelization” would have to be new, because the old evangelization was identified with tremendous human rights violations and genocide. Thus, any effective articulation of a “new evangelization,” he insists, must first face head-on the injustices associated with the spread of Christianity throughout the world.[9]

To conclude, there is strong evidence that diverse theologies and agendas of Catholic clerical and lay leaders today are being negotiated in large part the galvanizing and inclusive term “new evangelization,” which as Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion suggest, can thus be described as operating as as ideograph. The term’s plasticity allows its use among diverse groups and enables the Church to function as a “heterogeneous organization that responds in both progressive and conservative manners to various socio-political contexts.”[10] Yet their research, along with Smith’s, suggests that attempts by its key NE figures and groups to draw the language, mission, and practices of groups that closely identify with liberation theology and Catholic social teaching into the wider mission (and rhetoric) of the NE reflects deeper theological tensions.[11] Thus, for proponents of liberation- and social justice-oriented theologies, to appropriate or reject “new evangelization” rhetoric remains a complicated strategic and theologically-freighted choice.

[1] National Conference of Catholic Bishops (eds.). “Santo Domingo Conclusions (Fourth General Conference of Latin American Bishops),” trans. by Phillip Berryman (Washington, D.C.: National Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1992), 50. In Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion, “Specialized, Ecclesial Ideography,” 8.

[2] Ibid., 97-102.

[3] Ibid., 57-59.

[4] Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion. “Specialized, Ecclesial Ideography,” 9.

[5] Christian Smith. “Las Casas” as Theological Counteroffensive: An Interpretation of Gustavo Gutiérrez’s “Las Casas: In Search of the Poor of Jesus Christ,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41.1 (2002), 69-73.

[6] Gustavo Gutierrez, Las Casas: In Search of the Poor of Jesus Christ (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1993), 262-3.

[7] Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion. “Specialized, Ecclesial Ideography,” 7.

[8] Christian Smith. “Las Casas” as Theological Counteroffensive,” 69-73. Emphasis mine.

[9] See L. Boff. New Evangelization: Good News to the Poor (Nova Evangelizaca: Perspectiva dos Oprimidos) trans. by Robert R. Barr (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991).

[10] Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion. “Specialized, Ecclesial Ideography,” 9.

[11] Bennett-Carpenter and McCallion. “Specialized, Ecclesial Ideography,” 7.