As the Irish football team has another road game this week, those not traveling to the game will have to catch it somewhere else. In this day and age, football fans have a variety of media options to follow the score through television, radio, and the internet, making it virtually possible to get updates in every corner of the planet with decent reception.

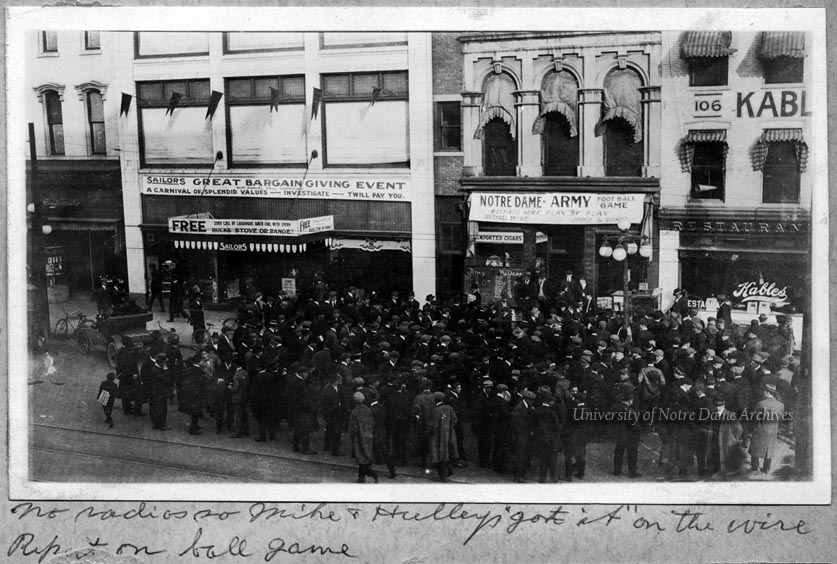

In the early 20th century, students and fans heard the news from telegraph wires reporting the score. They would gather in downtown South Bend at popular hang-outs such as Jimmie & Goat’s Cigar Store, the Palais Royale, and the Oliver Hotel, to hear the play-by-play action.

By the 1920s, Notre Dame offered game watches to students and the local community inside the Fieldhouse with the full fanfare of the Marching Band. If the Band happened to join the team on the road, a local orchestra might fill-in to provide musical entertainment. In 1924, Notre Dame acquired an electric Gridgraph, which used lights to demonstrate the play-by-play account. Various student organizations ran the Gridgraph and covered its operation cost by charging an admission fee, generally under twenty-five cents. The University Archives of Michigan and Missouri have good examples of what an electronic Gridgraph looked like.

The 1922 homecoming game versus Indiana at Cartier Field was the the first Notre Dame game broadcast by radio and was aired on South Bend’s WGAZ (later WSBT). However, “it is unknown whether anyone even heard this broadcast.” As radio was a brand new medium, few households actually owned radios and there were no ratings reports at the time. In 1923 and 1924, New York stations broadcasted the Notre Dame versus Army and Princeton. The first Notre Dame home game to be broadcast outside of South Bend was the 1924 game versus Nebraska at Cartier Field on Chicago’s WGN [Gullifor, pages 4-6]. This new medium would revolutionize game “watching,” bringing fans closer to the action, and eventually making the Gridgraph obsolete.

Unlike other schools in the 1930s and 1940s, Notre Dame did not give any one radio network exclusive rights to broadcast the football games. Instead, the field was open to many different broadcasters around the country. This in turn helped strengthen Notre Dame’s unique position of having a nationwide fan base, whose groundwork was started even before Knute Rockne. This open broadcasting policy also had some seemingly eternal consequences for Notre Dame: “fan expectations for national championships and … the Irish football coach work[ing] in a fishbowl” [Sperber, page 453].

Former Irish football player Joe Boland established the Irish Football Network on the radio through WSBT in 1947. Boland grew the coverage to include 190 stations, including the American Armed Forces Network, which broadcasted the games worldwide. The Mutual Broadcasting System “outbid the Irish Football network for exclusive rights to the 1956 home season.” Despite Boland’s tireless work to grow the Irish Football Network and dedication to his alma mater, Mutual could offer Notre Dame more revenue and broader coverage on over twice the number of radio stations [Gullifor, page 51].

Also during this time, fans could see game highlights as part of new reels at the movie theater. Fans in select cities could watch the entire game in theaters for weeks after the game took place. For instance, the 1927 Notre Dame versus Southern California football game, held at Soldier Field in Chicago, was filmed and screened days afterwards at the Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium. On a special “USC night,” three days after the game had been played, an audience of 4500 came to watch the game film, complete with the USC band providing musical accompaniment (spoiler alert: ND won the game 7-6) [Los Angeles Times, “Film Show Delayed by Union Row,” 11/30/1927].

The first televised game was home against Iowa in 1947. University President Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh and Athletic Director Edward “Moose” Krause had dreams of having regular national television coverage of Notre Dame football games. However, they were deterred by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), who banned “individual deals by member schools” [“Prime Time” by Richard Conklin, Notre Dame Magazine, Autumn 1991].

From the 1950s-1980s, Notre Dame worked within the NCAA’s restrictions regarding the number of nationally broadcast games a year. Regional coverage was an option, as was closed-circuit networks. In 1955, Notre Dame offered a live closed-circuit television network, which broadcast three games to select hotel ballrooms across the country. The lucky cities to receive coverage were Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, Rochester (NY), St. Louis, and Washington, D.C.

A 1984 US Supreme Court decision overturned the NCAA’s stronghold over national television contracts with individual schools. In 1990, Notre Dame became the first college to sign an exclusive television contract with a national broadcast company (NBC) to televise the home games. More recently, other conferences and schools have brokered similar deals by creating their own presence on cable and the internet, including the Big Ten Network and Texas’ Longhorn Network. Notre Dame also offers exclusive content online, and is expected to grow exponentially in the coming years. As technology advances and as more people demand 24 hour content from their favorite school, it is clear that there is a lot of potential for the fan experience to continue to evolve and expand.

Sources:

The Fighting Irish on the Air: The History of Notre Dame Football Broadcasting by Paul Gullifor

Shake down the Thunder by Murray Sperber

Los Angeles Times, “Film Show Delayed by Union Row,” 11/30/1927

PNDP 3020-B-01

PNDP 3020-G-01

GMIL 1/08

PATH Football Programs

PATH Closed Circuit Television Network

GRMD 11/42

Boating Club on the lake, c1867-1874.

Boating Club on the lake, c1867-1874. Crew of the Silver Jubilee, 1896

Crew of the Silver Jubilee, 1896 Students around the Boat House on St. Joseph Lake, 1893

Students around the Boat House on St. Joseph Lake, 1893 Freshman (Class of 1916, upper-left), Sophomore (Class of 1915, lower-right), Junior (Class of 1914, upper-right), and Senior (Class of 1913, lower-left) Class Crew teams who competed in the 1913 Commencement races. The Freshmen defeated the Sophomores, and the Juniors, with Knute Rockne on the team, defeated the Seniors.

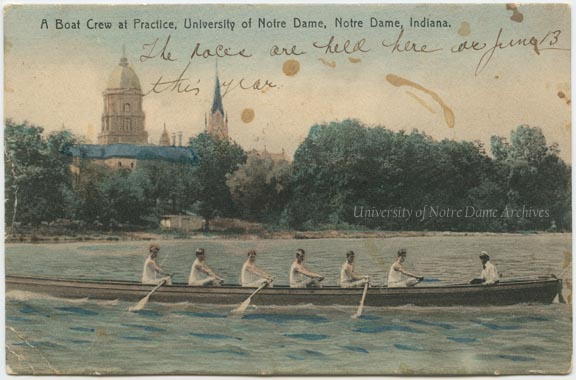

Freshman (Class of 1916, upper-left), Sophomore (Class of 1915, lower-right), Junior (Class of 1914, upper-right), and Senior (Class of 1913, lower-left) Class Crew teams who competed in the 1913 Commencement races. The Freshmen defeated the Sophomores, and the Juniors, with Knute Rockne on the team, defeated the Seniors. Postcard of a boat rowing crew practice on St. Joseph’s Lake with Main Building and Sacred Heart Church Basilica in the background, c1910

Postcard of a boat rowing crew practice on St. Joseph’s Lake with Main Building and Sacred Heart Church Basilica in the background, c1910 Women’s Varsity Crew team rowing on St. Mary’s Lake with the Main Building Dome, Hesburgh Library, and Basilica of the Sacred Heart in the background, 1999-2000

Women’s Varsity Crew team rowing on St. Mary’s Lake with the Main Building Dome, Hesburgh Library, and Basilica of the Sacred Heart in the background, 1999-2000

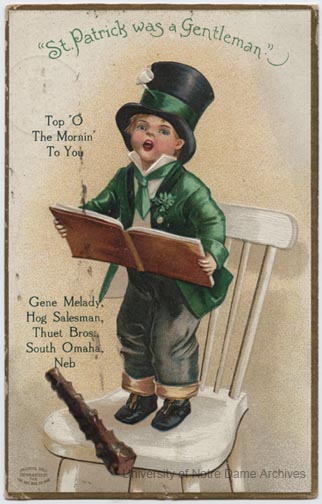

band in front of the college and in the afternoon Randolph and myself and four other boys went asked one of the Brothers to take us up in the steeple [of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart] to see the Bells which he did immediately so when we got up their three or four of the boys tapped to see how loud it would sound the bell weighs seventeen thousand pounds and, it takes four men to wring it and after he’d played two or three tones by chains. And still St. Patrick was not over yet in the evening they all assembled in the Rotunda of hear some of the boys speak in which George Clark delivered a very fine piece of poetry he is the best speaker of the students of Notre Dame and is a resident of Cairo, Illinois. This is all for the present, so when you receive this letter I suppose you will answer it with more latitude than the last, for I suppose that time are not so hard. Best regards,

band in front of the college and in the afternoon Randolph and myself and four other boys went asked one of the Brothers to take us up in the steeple [of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart] to see the Bells which he did immediately so when we got up their three or four of the boys tapped to see how loud it would sound the bell weighs seventeen thousand pounds and, it takes four men to wring it and after he’d played two or three tones by chains. And still St. Patrick was not over yet in the evening they all assembled in the Rotunda of hear some of the boys speak in which George Clark delivered a very fine piece of poetry he is the best speaker of the students of Notre Dame and is a resident of Cairo, Illinois. This is all for the present, so when you receive this letter I suppose you will answer it with more latitude than the last, for I suppose that time are not so hard. Best regards,