吃了吗?

(As I recently learned, asking if a friend recently ate serves as a substitute for saying hello, an appropriate segue way into…)

In a sort of coincidence (that I’m going to chose to interpret as divine intervention for the sake of a dramatic blog), the very topic I fussed over as the most glaring shortcoming in my ability to express my daily needs, all required for ordering food, was the central focus covered in the past week. While this laid the foundation for understanding a dish’s components, I am nowhere near being able to boast that I could translate any item from any menu in any restaurant, especially given the sheer enormity of variety in Chinese cuisine. In fact, our daily lesson included an adage on the eclectic melange in every kitchen: “带翅膀的除了飞机什么都能吃,四条腿的除了桌椅什么都可以吃,” — besides those of an airplane, you can eat any wing; besides the four under a table or chair, you can eat any leg. Hardly the musings of Confucius, but equally as pithy and equally as observant. Now three and a half weeks into the program, I cannot think of any saying more adequate.

Except maybe a joke told by our program’s Professor Zhu. In response to a few remarks regarding the 很奇怪 meats with which we were not acquainted as we gathered around the ubiquitous Lazy-Susan style dining table, Zhu Laoshi told us about a Chinese man that once went on a safari in the African savannah. While exploring the man was bitten by the world’s most venomous snake. Instead of keeling over dead, the man stood and watched as the snake keeled over from ingesting the digested foods in his own system, potent enough to kill even the beast. Though said in warning of the imminent food poisoning we may expect, which I thankfully have yet to experience, I think the humor holds a definitive truth to it.

Apart from the dining room, I am pleasantly surprised the degree to which I learn from exploring the jungle that is Beijing. I am endlessly thankful the subway systems and most street signs also include the pinyin pronunciation of the characters it displays, so I can practice the reading and speaking aspects of the language wherever I go. I have found that many formal names are compounded words of simpler building blocks, which with repeated exposure I have begun to recognize and piece together. For example: Tian’anmen Square’s name comes from 天 安 门 tiān (sky, heaven) ān (peace) mén (gate, door) meaning the Gate of Heavenly Peace. Elsewhere, Wudaokou, the name of a nearby neighborhood means the Opening of Five Pathways. With components like these, I’ve been able to decipher the names of other places around Beijing, typically including place words like bridge, alley, gate, pathway, etc.

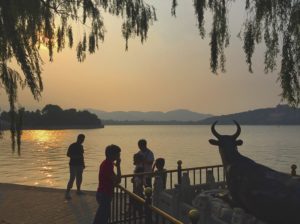

The Summer Palace was especially interesting to apply this pattern. Retaining many of its original heavenly and or naturally derived names and the context of the feature allows me to circumvent the English translation and anticipate the meaning of the unknown vocabulary. Accordingly, I’ve learned words I would otherwise not think to look up for usage, like “arch” from 十七孔桥, the Seventeen Arch Bridge, pictured below. Besides the strictly academic benefits of visiting the Summer Palace on a lazy, hazy Sunday afternoon, the proximity to campus and the traditional buildings surrounding the scenery of the Kunming Lake made the site easily one of my favorites in Beijing.

The more I explore, the more I fully realize the total dichotomy of this country. On Saturday afternoon, the program visited 798, Beijing’s modern arts district, situated at the foot of steel high-rises in repurposed brick factory buildings from the nascency of the communist industrial booms in the 1950s. But on Sunday afternoon, I climbed the stone paths to survey the Sea of Wisdom Temple and Hall of Buddhist Incense from nearly half a century ago. All within the same country. All within the same half of the same city. But lest I forget a half of this modernized ancient country, a pagoda will ornament the mountain ranges beyond the sky-scraping Central Business District or the steely skyline will assert itself through the view of a modest temple.