1.

With time for reflection—as well as readjustment to the U.S.—I am now looking back on my SLA experience with all its boons as well as bumps. Ultimately, I feel that I accomplished what I set out to do: to both advance my Japanese ability and develop an understanding of the Japanese people: how they think, feel, view the world. As expected, living with a host-family and taking Japanese classes improved my language, my vocabulary and grammar particularly having grown in scope. However, my speaking and listening have improved, as well. On first arriving in Japan, I had difficulties hearing what Japanese speakers were saying, owing in large part, I think, to native pace and inflection. But by the end of the program, I was having fairly natural conversations with native speakers, and if I ever encountered a hiccup (not knowing how to express a word, or not understanding a phrase) I could clarify or specify in the moment. But I have also come to a greater understanding of Japanese people, owing to language tables with university students, trips to shrines or hot springs or simply corner restaurants, and, of course, the unforgettable opportunity of living with a host-family.

2.

I find that my eight weeks in Japan presented challenges that I had not anticipated, perhaps the greatest of which being self-questioning. For all the inspiring places I visited, all the kind people I met, the skills I was developing, I still felt doubt. “Maybe I am not meant to learn Japanese. Perhaps I will never truly have a place in this country. Will I ever grasp the society and its expectations?” I think much of this doubt stemmed from those days when I encountered a complicated grammar point or I struggled with my conversational skill. As an English major, I am so accustomed to complex expression that having to lower myself to a simpler level of diction, ideas, etc. in Japanese was frustrating. If I have any advice, it is that making connections with natives during the abroad experience is critical. In order to not feel like a stranger and more like a student of international exchange, having a native to relate to and discuss your frustrations with can help close that gap of doubt, of fear, of listlessness. It sounds trite to say “Make friends,” but it is no less important a truth of the abroad experience.

3.

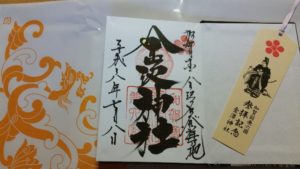

For the Fall semester of 2016, I am returning to Japan to continue my studies at Nanzan University. During this experience, I will be staying with another host family while taking classes both in Japanese language and culture. The SLA experience has not only prepared me linguistically for a longer stay in Japan but it has also helped tune me to Japanese culture and lifestyle so that when next I arrive in Japan it will be with greater intuition. With so much direct exposure to Japan during my undergraduate career, I am setting myself up for a longer pursuit of professional work in or in connection with Japan. In my pre-departure planning for SLA, I reflected on the possibility of joining the J.E.T. (Japanese Exchange and Teaching) Program or a program of similar focus after graduation, and after going abroad, I am still strongly considering this option. Outside of my professional intent, living in Japan and having an opportunity to learn about new sets of traditions, folk tales, and philosophies—particularly through my interest in Shintoism—have inspired me as a writer, and my creative interest in Japan grows the more I can engage with Japanese art directly through language.

Thank you for reading.

Joshua Kuiper

カイパーヨシュア