Personal Family Experience Caring for a Loved One

A few years ago, my grandmother was diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia, which is a rare neurological syndrome that affects the ability to communicate. The first symptom my grandmother experienced was losing the ability to speak, so she communicated by writing down her thoughts. Over time, she lost the ability to write as well. Eventually, it became apparent that my grandmother could not understand what other people were saying to her. During the final few years of her life, my grandmother could no longer perform daily tasks such as going to the bathroom or feeding herself.

During the early years of my grandmother’s disease, my grandfather took care of her. He assisted her as she tried to communicate with others and helped her navigate the world. When my grandmother’s condition started to worsen, my aunt stepped in to provide additional assistance and care. Ultimately, my grandfather and aunt decided it was best to put my grandmother in a nursing home to have professional nurses and caregivers help care for her.

Although my grandfather and aunt still spent a lot of time caring for my grandmother while she was in the nursing home, they did not have to spend all hours of the day watching over her and tending to her needs. However, many people in the U.S. are not able to put their loved ones in nursing homes or hire extra help, whether it may be due to financial or cultural reasons, and are forced to spend all their time and energy acting as unpaid caregivers.

Statistics of Unpaid Caregivers in the U.S.

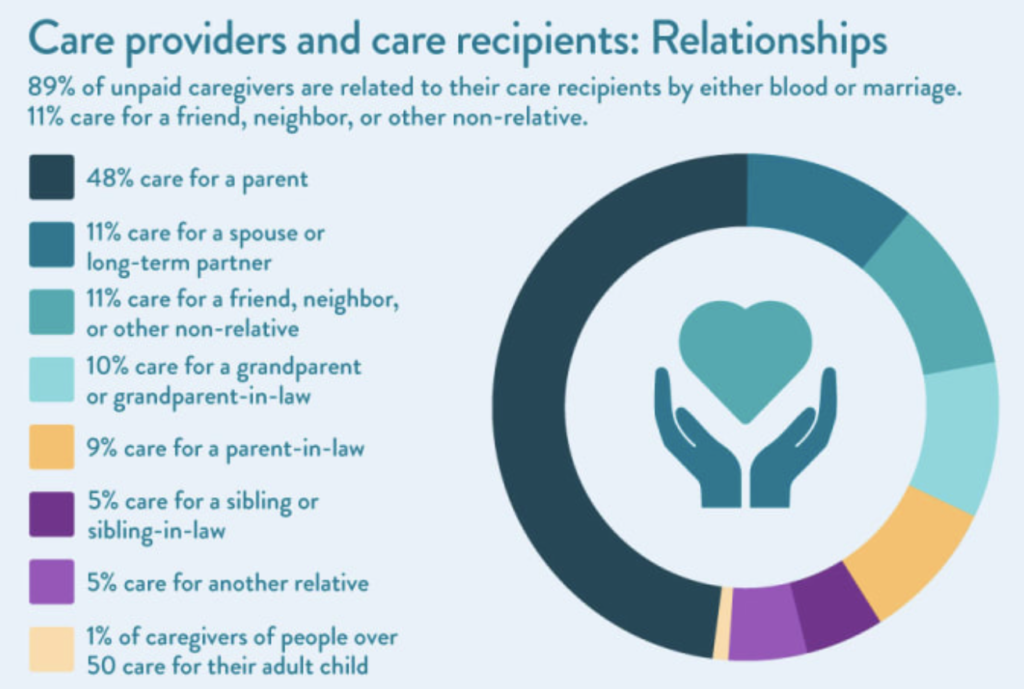

About 20 percent of the U.S. adult population, or about 50 million U.S. adults, provides unpaid care to an adult over the age of 50. Over 75 percent of these unpaid caregivers are women. Most unpaid caregivers spend the same amount of time working as a caregiver that people spend working a full-time job. Additionally, many of these caregivers are employed or are raising their own children at the same time. It is estimated that caregivers provide about 470 billion dollars in free labor each year.

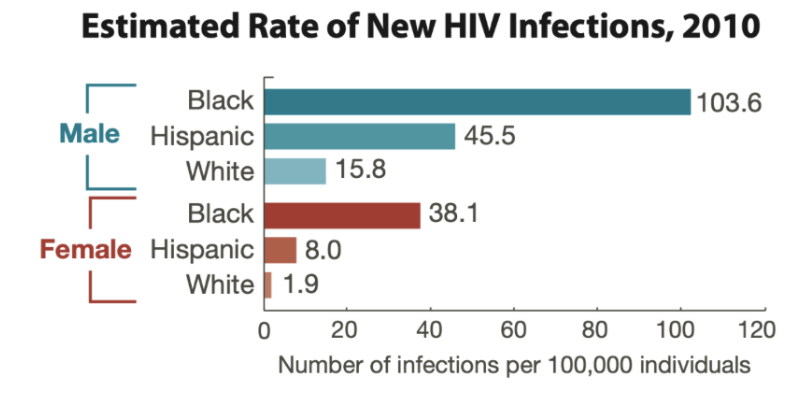

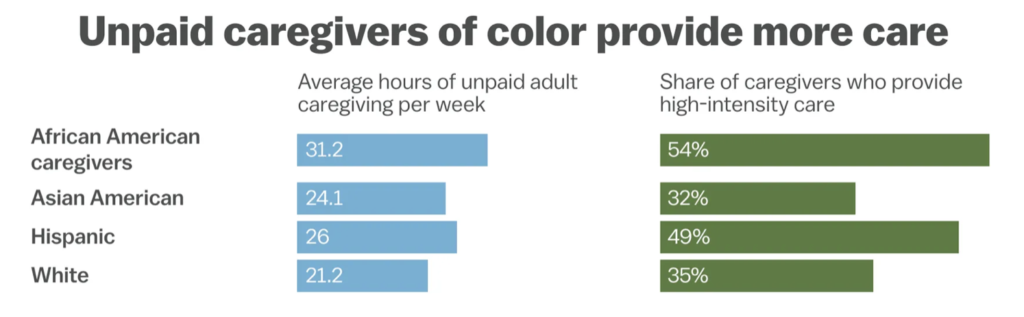

The vast majority of unpaid caregivers provide care to a relative. A few unpaid caregivers provide care to a non-relative, such as a friend or neighbor. Some of the tasks that unpaid caregivers perform include preparing meals, cleaning, assisting with dressing and bathing, and providing transportation to and from medical appointments. It is important to note that race and ethnicity play a large role in the makeup of unpaid caregivers in the U.S. African Americans provide the most hours of unpaid adult care per week, followed by Hispanics, then Asian Americans, and finally white Americans according to an AARP report.

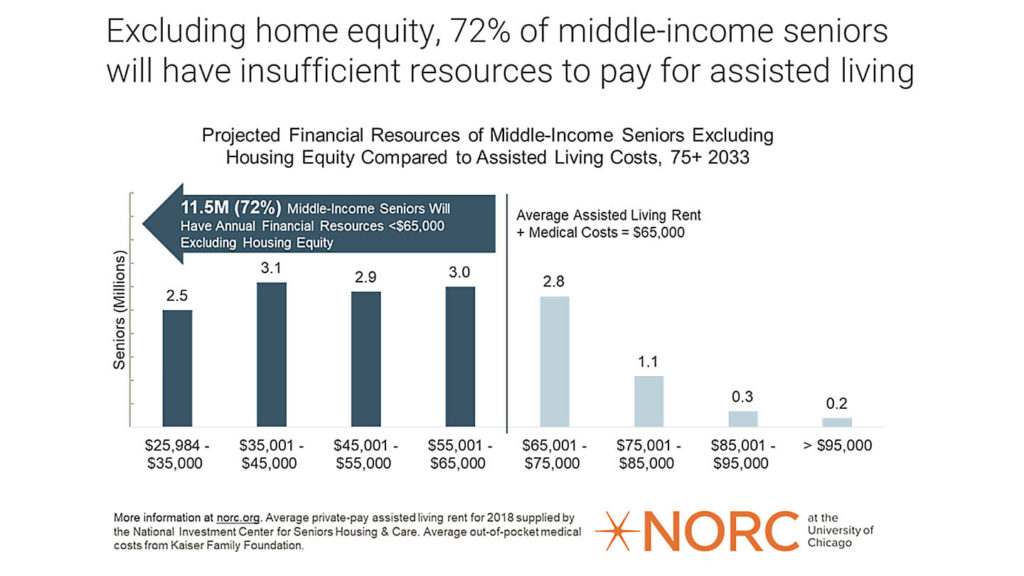

Providing unpaid care takes a mental toll on the caregivers, and it causes a financial strain. Providing unpaid care for multiple hours a week results in impaired self-care and increased depression and psychological distress. Also, family caregivers spend over 7,000 dollars annually, equating to 26 percent of their income, on providing care to a senior loved one on average. In addition, about 22 percent of caregivers report using all their short-term savings, while 12 percent say that they went through all their long-term savings while providing care for elderly parents at home according to an AARP report.

The Effects of Covid-19 on Unpaid Caregivers

“The coronavirus pandemic has revealed many problems in our health system, and few more starkly than the way it both undervalues and relies on caregivers.”

Kate Washington, The New York Times

Covid-19 has placed an even greater strain on unpaid caregivers than before the pandemic. An example can be seen with Sabrina Nichelle Scott, a black woman who left her job in 2016 to become the primary caregiver for her grandmother Lillian, who had dementia. Scott had developed a good system of caring for her grandmother until the pandemic hit. Once Covid-19 came into play, Scott had to provide round-the-clock care in her grandmother’s Harlem apartment because the outside world became too risky. Lillian refused to wear a mask, which confined Scott and her grandmother to the small Harlem apartment. For the first few months of the pandemic, Scott did not get any breaks from caring for her grandmother. As a black woman, she felt even more pressure to be an intensive caregiver due to black culture and the resistance from other family members to the idea of getting more skilled care for Lillian. Lillian eventually died in March 2021, and although Scott is glad to have been able to help her grandmother, she reports being traumatized from the experience.

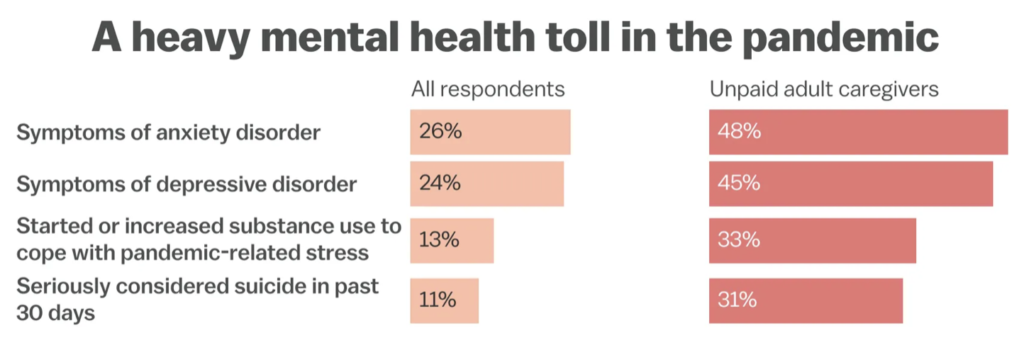

Scott is not the only unpaid caregiver whose mental health was affected from caring for a loved one during the pandemic. According to a survey conducted by the CDC, unpaid adult caregivers had higher rates of anxiety disorder and depressive disorder symptoms compared to all respondents, and unpaid adult caregivers had higher rates of seriously considering suicide. In addition to affecting many unpaid caregivers for older adults, the Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a greater demand to provide care for children due to the closure of schools and daycares, and most of this responsibility has fallen on women. These women also reported higher rates of mental strain, such as depression.

Conclusion

The U.S. has millions of unpaid caregivers that suffer mental and financial burdens in silence, and people of color are disproportionately affected by the need to act as an unpaid caregiver. The U.S. government needs to act to support unpaid caregivers. Not many caregivers can pay for additional help or put their loved ones in a nursing home like my family was able to do for my grandmother who suffered from advanced primary progressive aphasia. In order to relieve some of the burden felt by unpaid caregivers who have to provide intensive care for their loved ones, the U.S. government needs to create programs and provide money to these caregivers.

Works Cited

Courage, Katherine Harmon. “America Isn’t Taking Care of Caregivers.” Vox, Vox, 4 Aug. 2021, https://www.vox.com/22442407/care-for-caregivers-mental-health-covid. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Family Caregiver Alliance. “Caregiver Statistics: Demographics.” Family Caregiver Alliance, https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Mayo Clinic Staff. “Primary Progressive Aphasia.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 27 Dec. 2018, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/primary-progressive-aphasia/symptoms-causes/syc-20350499. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Ranji, Usha, et al. “Women, Work, and Family During COVID-19: Findings from the KFF Women’s Health Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 22 Mar. 2021, https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/women-work-and-family-during-covid-19-findings-from-the-kff-womens-health-survey/. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Samuels, Claire. “Caregiver Statistics: A Data Portrait of Family Caregiving.” APlaceforMom, 2 Dec. 2022, https://www.aplaceformom.com/caregiver-resources/articles/caregiver-statistics. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Schoch, Deborah. “1 In 5 Americans Now Provide Unpaid Family Care.” AARP, 18 June 2020, https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2020/unpaid-family-caregivers-report.html. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Washington, Kate. “50 Million Americans Are Unpaid Caregivers. We Need Help.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Feb. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/22/opinion/us-caregivers-biden.html. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Washington, Kate. “50 Million Americans Are Unpaid Caregivers. We Need Help.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Feb. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/22/opinion/us-caregivers-biden.html. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.